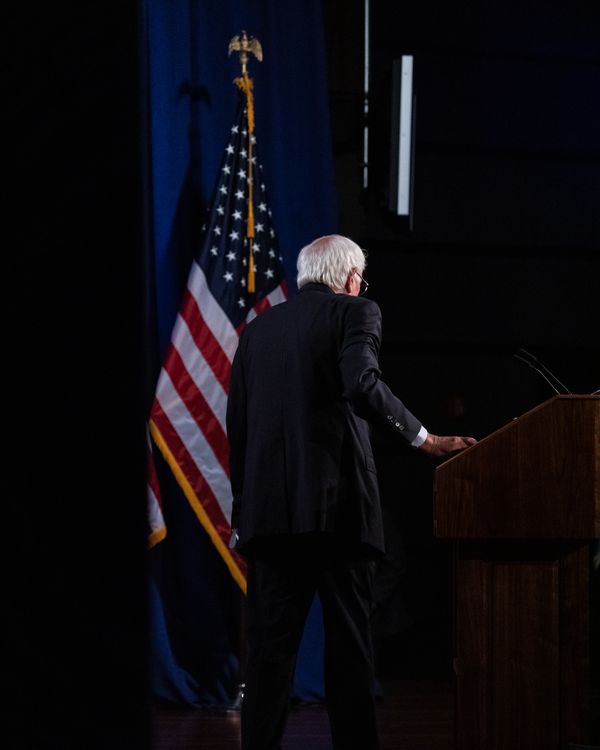

Bernie Sanders spent lots of time talking on the phone during his two weeks off the campaign trail post–heart attack earlier this month. There were the uneventful well-wishing calls he and his wife Jane got from his rivals in the 2020 presidential race, and from some political allies. (Harry Reid, for one, visited in person while Sanders was still hospitalized in Las Vegas.) There were some more eventful ones, like the “I’m going to endorse you” call he got from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, routed through his campaign manager Faiz Shakir. And, once it pretty quickly became clear to Sanders’s aides in both Las Vegas and Washington that he would be able to resume campaigning, and that they should map out next steps, there were the reassurance calls.

No one, after all, knew what to expect from the 78-year-old, who had just suffered his first heart attack. At his campaign headquarters in D.C., for example, Sanders’s staff gathered three times to hear formal updates while news trickled out from Nevada, then Vermont. Sanders himself called in once to speak with, and rally, the assembled operatives. They’d just come through a long summer that included some undeniably rough patches, politically speaking, both internally and because of the rise of Elizabeth Warren. The campaign had remained mostly quiet in the early days of Sanders’s hospitalization, holding off for days before confirming late on a Friday that he’d suffered a heart attack. But its few informal public communications were starting to shape a message — the day Sanders was discharged and returned to Vermont, senior adviser Josh Orton tweeted a link to a video of “Willy Wonka’s Grand Entrance” and titled it “NEW footage of Bernie leaving the hospital.” Sanders’s top aides now wanted the full staff in on the plan: Sanders would remain at home, recovering, for two weeks until the next debate, but they were to push ahead as hard as ever. The voters needed reassuring, too.

So while Sanders met with his inner circle back in Burlington and began prepping in his backyard for the debate the same way he always did — a casual back-and-forth, not a formal mock session — his campaign began putting out new formal policy proposals (with Sanders weighing in over the phone). It resumed an Iowa television ad buy that it had temporarily suspended, and it advertised a wave of surrogate campaign events in early-voting states. With uncertainty about Sanders’s health circulating, it announced he would participate in a march “to end corporate greed” in Des Moines next month, and it distributed a video Sanders filmed to thank supporters for their messages. He sat for a pair of TV interviews. His teams in the states pushed the “full steam ahead” message, too: In Nevada, they said they’d now attempted over one million voter contacts and rolled out a slate of new community leader and educator endorsements; in New Hampshire, they announced campaign co-chairs; and in South Carolina, they opened an office in Florence County.

And they announced that on Saturday he’d be holding a major rally at Queensbridge Park, titled “Bernie’s Back.” Before long, they started teasing that there’d be a “special guest” there as well.

Still, some nerves lingered in Burlington as the senior brass prepared for Tuesday’s debate in Ohio. They knew Sanders would get a health question, but even if he was ready for that, this three-hour session would still be his return to the full-speed fray.

Yet by the time the candidate walked offstage and asked his aides how he did on Tuesday night, as he always does immediately after leaving debate stages, their mood had shifted considerably. Not only did Sanders exceed his skeptics’ expectations, the public now knew about the endorsements from Ocasio-Cortez and her fellow “Squad” member Ilhan Omar. (These endorsements were supposed to be rolled out later, but the news broke early.) The campaign’s attention was already shifting to Saturday, when Ocasio-Cortez would join Sanders onstage for the first time this year, a moment that had been in the making since she’d flown to Vermont late last month and sat with Bernie, Jane Sanders, Shakir, and one of her own aides for what Shakir called a meeting of “two ideological compatriots who see each other, who understand one another.”

Sanders’s advisers describe this moment now as a triumphant return to the trail just in time for the campaign to get serious. “November is exactly when we want to be going up, showing momentum,” said Shakir, describing Ocasio-Cortez’s presence onstage as “the kind of movement that shakes” the hard-to-mobilize voters Sanders needs by his side. The senator’s team is in talks with the congresswoman’s about a trip to Iowa, too, Shakir said. Longtime Sanders adviser Jeff Weaver said he expects the candidate to soon return to something like his typical breakneck campaign speed: “Obviously the health incident raised some immediate questions, and it was obviously important to demonstrate what was the case — which was he was on the road to recovery and will be campaigning vigorously.” The political revolution, in this telling, is back on track.

The truth is that this is, indeed, an inflection point for Sanders, but a far more delicate one than he or his allies readily admit. In fact, how the candidate handles the next month could determine the rest of his trajectory in the race.

Sanders, who has yet to release promised medical information, and who has switched his primary campaign message from Medicare for All to electability and back multiple times, is reemerging just as more voters are watching the race more closely than ever, and just as Warren, the newly minted front-runner, faces centrist fire for the first time, and just as his campaign brain trust hopes his 2016 supporters come home to him.

Notorious among his allies for his resistance to talk about his personal life, Sanders is hoping to move on from the health question. At earlier stages of his political career, he’s bristled when asked about his health.

It was never a campaign issue in 2016, after Hillary Clinton ally David Brock floated the idea of calling for Sanders to release his medical records early in the primary, only to face a huge internal backlash. Still, Sanders liked making a point of taking it off the table. During that campaign, some of his early ads included shots of him running during his student days and playing baseball as an adult, and he enjoyed playing basketball in front of the cameras. In the lead-up to the 2020 race, he participated in multiple long marches — once, when a CNN anchor asked Weaver about Sanders’s health following such a campaign event in Indiana, Weaver shot back that the reporter was struggling to keep up with the hearty Sanders. Sanders told New York that week, “I thank God, you know, I can’t remember the last day — honestly — when I missed work.” He continued, “What people have a right to know: Is the candidate healthy? Does he or she have the energy to do what is a very stressful and difficult job?” On the debate stage this week, he pointed to his Saturday rally when asked about his heart.

Now, though, he’s tasked with moving past these questions just when he has to catch back up to Warren and eclipse Joe Biden. He lost ground over the summer, and entering the fall, he tossed out and rebuilt parts of his Iowa team and completely overhauled his operation in New Hampshire, a must-win state for him where he is now polling third.

And while polling since his heart attack has been scant, the early indications haven’t been good: The most recent national Quinnipiac poll showed Sanders’s support dropping over the course of the previous week, including significant drops among non-college-educated white voters and very liberal voters — two groups he can ill afford to lose. Meanwhile, a HuffPost/YouGov survey had just 28 percent of Democrats assessing Sanders as being in adequate physical condition for four years of the presidency.

The imperative for a blockbuster return to the scene, then, is strategically obvious. It started with the debate, continued with the rollout of Omar’s endorsement video the next morning, and will peak with Saturday’s rally with Ocasio-Cortez, one of the party’s biggest stars. Soon Sanders will appear with Rashida Tlaib, another “Squad” member, in Michigan, ahead of another expected endorsement.

The question, really, is what comes after that, once he returns to typical campaign events.

Some of Sanders’s close aides were delighted when the senator’s first comments after his hospitalization were about the need to implement a Medicare for All system, and they expect him to lean back into that signature plan as the centerpiece of his campaign. “We will ratchet it up on Medicare for All,” said longtime labor leader Larry Cohen, a veteran Sanders adviser who chairs the board of the Sanders-spawned Our Revolution outside group. Others see merit in a punchy tack that directly takes on Biden, specifically over the health-care question. Already, on Thursday, Sanders issued a statement decrying Biden’s use of “the talking points of the insurance industry to attack Medicare for All,” and a Friday fundraising email from the campaign echoed this line.

What they all agree on now is that Sanders is intent on digging back in for the long haul, not transitioning to a new kind of campaign, as he’d hinted, then walked back, in recent weeks. The Saturday rally isn’t just about reenergizing his base and bringing in new voters, said Cohen. It’s also a signal of a long slog ahead. That’s because in his telling, it’s a statement of intent about the New York primary.

That contest is likely to be the final opportunity for candidates who are still standing to pick up large numbers of delegates. And it’s not for another six months.