Having just emerged from one scandal of foreign influence in Eastern Europe, President Trump immediately became embroiled in another — driving House Democrats to finally launch an official impeachment inquiry this week. The central allegation: In a July 25 phone call, Trump pressured Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate the business dealings of Joe Biden’s son, as he was holding up U.S. aid to the country. (Though Bloomberg cast doubt on the claim that the former vice-president interfered in Ukrainian politics to aid his son Hunter, Trump could still use the story against his potential 2020 rival.) The call came to light via a complaint from an intelligence-community whistle-blower, which Trump officials initially withheld from Congress. The 9-page complaint, which was made public this week, describes Trump administration efforts to cover up what the president told he Ukrainian counterpart, and Rudy Giuliani’s key role in urging Ukraine open investigations that could influence the 2020 election.

Here’s everything we know about Trump’s Ukrainian call, his administration’s attempt to conceal it, and the Democrats’ impeachment push.

The latest

• The declassified version of the whistle-blower’s complaint was released to the public on Thursday morning.

•Democrats anticipate that impeachment articles could be ready by around Thanksgiving.

What Trump said during the phone call

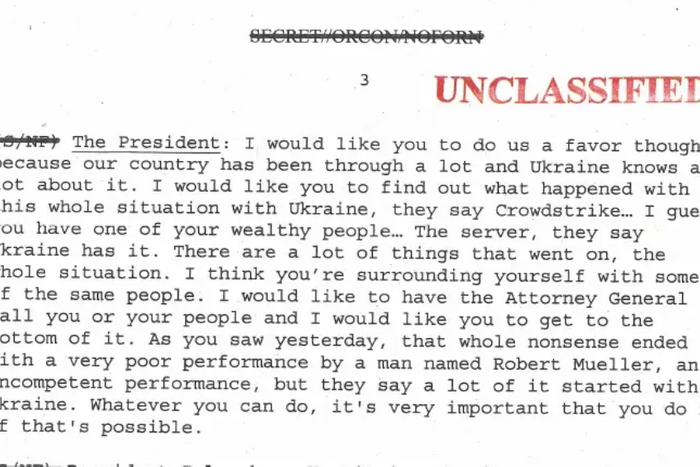

The White House released a limited transcript of Trump’s call with Zelensky on Wednesday morning. It shows Trump repeatedly urging the Ukrainian president to work with his personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, and Attorney General Bill Barr to open a corruption inquiry, which Trump links to Joe Biden.

After they exchanged pleasantries about Zelensky’s recent election win, the Ukrainian president thanked Trump for previous U.S. aid (he was not yet aware that Trump had blocked $391 million in aid to Ukraine days earlier). Trump immediately shifted the conversation to investigating Democrats.

“I would like you to do us a favor though because our country has been through a lot and Ukraine knows a lot about it,” Trump said, going on to reference CrowdStrike, the U.S.-based technology company that investigated the hacking of the Democratic National Committee in 2016, and former special counsel Robert Mueller.

Later in the conversation, Trump asked Zelensky to work with Barr and Giuliani to “get to the bottom” of corruption claims against Joe Biden.

“There is a lot of talk about Biden’s son, that Biden stopped the prosecution, and a lot of people want to find out about that,” Trump said. “So whatever you can do with the attorney general would be great.”

Though the document is formatted to look like a transcript of the call, it isn’t a verbatim record of the conversation. Democrats called the release a “highly edited memo” and were skeptical that a 30-minute conversation could be fully relayed in a five-page document.

Trump administration efforts to conceal the call

In the declassified complaint, the whistle-blower described the call as Trump “using the power of his office to solicit interference from a foreign country” in the 2020 election, and said he spoke to “multiple U.S. government officials” who raised concerns about the call.

The whistle-blower said that in the days following the phone call, he “learned from multiple U.S. officials that senior White House officials had intervened to ‘lock down’ all records of the phone call, especially the official word-for-word transcript of the call that was produced — as is customary — by the White House Situation room.” He noted that this indicates officials immediately “understood the gravity” of what Trump had said.

Officials told the whistle-blower that they were “directed” by White House attorneys to remove the electronic transcript from the computer system where it would usually be stored. Instead it was loaded into a separate system that is used to handle especially sensitive classified information. “One White House official described this act as an abuse of this electronic system because the call did not contain anything remotely sensitive from a national security perspective,” the whistle-blower wrote, adding that it’s unclear if any additional steps were taken, like destroying handwritten notes.

The White House confirmed on Friday that officials were told to file the Ukraine call in a different electronic system, saying National Security Council attorneys “directed that the classified document be handled appropriately.”

Officials told the New York Times on Thursday that they were also ordered not to distribute the transcript of the call electronically, as is customary. Instead, they were instructed to print out copies and hand deliver them to a select group of people.

Rudy Giuliani’s role in pushing the Biden-Ukraine story

The whistle-blower stated that in mid-May, he began hearing from multiple U.S. officials who were “deeply concerned by what they viewed as Mr. Giuliani’s circumvention of national security decision-making processes,” referring to Giuliani engaging with Ukrainian officials about investigating Democrats, and relaying messages back to Trump.

The Trump camp’s central claim is that Biden behaved improperly as vice-president, using his influence to demand that Kiev fire its top prosecutor, who had investigated a Ukrainian gas company where Hunter Biden was a board member. But in May, Bloomberg found the timeline doesn’t add up: The investigation into the energy company was long dead by the time Biden began calling for the prosecutor’s ouster. Plus, as New York’s Jonathan Chait notes, “the prosecutor was widely considered corrupt, his sacking was consistent with the administration’s pro-democracy agenda, and the Obama administration supported the investigation into Hunter Biden anyway.”

Nevertheless, Giuliani ran with the allegations, making no secret of his effort to push Ukraine into opening an investigation into Biden ahead of the 2020 election. In May, Giuliani made plans to travel to Kiev to discuss the matter with Ukrainian officials. In an interview with the New York Times at the time, the former New York City mayor openly admitted that he was pressuring the Ukrainians because it would be “very, very helpful” to Trump — though some might see that as “improper”:

“We’re not meddling in an election, we’re meddling in an investigation, which we have a right to do,” Mr. Giuliani said in an interview on Thursday when asked about the parallel to the special counsel’s inquiry.

“There’s nothing illegal about it,” he said. “Somebody could say it’s improper. And this isn’t foreign policy — I’m asking them to do an investigation that they’re doing already and that other people are telling them to stop. And I’m going to give them reasons why they shouldn’t stop it because that information will be very, very helpful to my client, and may turn out to be helpful to my government.”

Giuliani eventually abandoned the Kiev visit, but in August he met with a top Ukrainian official. As Giuliani told the Times, he “strongly urged” him to “just investigate the darn things,” referring to Hunter Biden and Ukrainian efforts to undermine Trump in the 2016 election.

When the whistle-blower story broke last week, Giuliani performed his typical TV routine on CNN, clashing with host Chris Cuomo and contradicting himself, claiming that he did not ask Ukraine to investigate Biden, before changing his mind about 30 seconds later.

Attorney General Bill Barr’s Role

The Justice Department said Barr was unaware that Trump told Zelensky he would contact him during their call, according to the New York Times. But Democrats quickly called out Barr for prioritizing his role as a partisan before that of attorney general, and for not recusing himself from the Department of Justice’s role in the whistle-blower complaint:

Trump’s decision to withhold aid from Ukraine

The timing of Trump’s decision to withhold almost $400 million in aid just days before speaking to the Ukrainian president suggests the possibility of a quid pro quo.

Trump’s response to the scandal

Trump initially admitted to discussing matters related to the Biden family in a call with the Ukrainian president, citing concerns about “corruption.”

“The conversation I had was largely congratulatory, was largely corruption, all of the corruption taking place,” Trump told reporters on Sunday, September 22, before the transcript was released. “It was largely the fact that we don’t want our people like Vice-President Biden and his son creating to the corruption already in the Ukraine.” He added that the exchange was “perfect” and involved no improper behavior.

A day later, Trump suggested it’s totally appropriate to withhold aid from a country because it won’t investigate your political rivals. “It’s very important to talk about corruption,” Trump said. “If you don’t talk about corruption, why would you give money to a country that you think is corrupt?”

Trump was reportedly in favor of releasing the transcript, as he felt it proved there was nothing problematic about the call. But after the fact, this move was widely viewed as a mistake, even among many GOP lawmakers.

Trump has been reusing his old claims about a Democratic “Witch Hunt!” on Twitter all week. During a private event on Thursday Trump lashed out at the whistle-blower, calling him “almost a spy” and commenting “You know what we used to do in the old days when we were smart, right? The spies and treason, we used to handle it a little differently than we do now.” He also called members of the press “scum” and “animals.”

House Democrats announce impeachment inquiry

Though a majority of House Democrats had previously said Trump should be impeached, after Mueller’s testimony flopped, the effort appeared to be dead in the water. The Ukraine scandal changed that in a matter of days.

At first, the story appeared to be trickling out slowly; last week confusing reports emerged about the administration withholding a whistle-blower’s complaint from Congress, but the subject of the memo was unclear. The pace intensified over the weekend, as it emerged that the complaint concerned a phone call in which Trump pressured the Ukrainian president to investigate Biden. Impeachment talk exploded on Monday night, with at least 14 House Democrats backing a probe for the first time this week.

Finally, following a Tuesday afternoon meeting with her caucus, Pelosi announced in a televised address that the impeachment inquiry was on.

“The actions of the Trump presidency have revealed the dishonorable fact of the president’s betrayal of his oath of office, betrayal of our national security, and betrayal of the integrity of our elections,” Pelosi said. “Therefore, today, I am announcing the House of Representatives is moving forward with an official impeachment inquiry.”

The Republican response to the scandal

Republicans have been cautious; while no congressional Republicans seem close to backing impeachment, only a few loyalists seemed eager to defend Trump.

Senator Mitt Romney was the most critical of the president, calling the allegations “troubling in the extreme.” Trump responded with a tweet mocking Romney for losing the presidency in 2012.

A day later, Romney said of impeachment, “it’s early to be having those conversations. There’s so much we don’t know.”

Some Republicans, including retiring Representative Will Hurd and Senator Ben Sasse, said more explicitly that they think Trump’s actions warrant further investigation – just not an impeachment investigation.

On Thursday, Vermont’s Phil Scott became the first Republican governor to back the impeachment probe. Scott, who has been critical of Trump in the past, cautioned that he wants to know more before further steps are taken.

The fight over the whistle-blower complaint

The battle over the complaint that brought the story to light began on August 12, when an unidentified member of the U.S. intelligence community submitted a complaint to (Trump-appointed) Intelligence Community Inspector General Michael Atkinson.

Atkinson reviewed the complaint, found it to be credible and of “urgent concern,” and, on August 26, sent it to the recently appointed acting director of national intelligence, Joseph Maguire. Per statute, Maguire was required to report the claim to the intelligence committees in the House and Senate within a week — but he said nothing. On September 9, Atkinson wrote the committees to make them aware of the existence of the whistle-blower complaint and Maguire’s failure to report it.

House Intelligence Committee chairman Adam Schiff wrote Maguire the next day, subpoenaing the complaint and accusing him of breaking the law. On September 13, DNI general counsel Jason Klitenic responded to Schiff, saying that after consulting with the Justice Department, they had overruled the inspector general. In their determination, the complaint was not of “urgent concern,” as it “concerns conduct by someone outside of the Intelligence Community” (i.e., the president), and it “involves confidential and potentially privileged communications.”

Schiff immediately rejected this explanation, insisting that the DNI lacks the authority to overrule the inspector general. After initially defying Schiff’s subpoena to supply the complaint or appear before Congress, Maguire appeared before the House Intelligence Committee in a televised hearing on Thursday, September 26. Maguire insisted he is “not partisan,” and said he resisted handing over the complaint because the White House counsel’s office told him it was a matter of executive privilege. He said the whistle-blower “did the right thing,” and that the president pressuring a foreign government for help with a U.S. election is “bad for the nation.”

Schiff said the whistle-blower may testify before the House Intelligence Committee in the coming days.

On September 30, following a theory published in the Federalist, Trump claimed that whistle-blower rules were changed just before the intelligence officer submitted his complaint. To get ahead of the false idea, the intelligence community inspector general issued a rare letter debunking the concern, informing the president that the form the whistle-blower filled out has been the same since May 2018. Dispelling the GOP conspiracy that the whistle-blower was operating on “hearsay” information, the IG also stated that they possessed “direct knowledge of certain alleged conduct.”

Who is the whistle-blower?

The whistle-blower has yet to be publicly identified, but according to a controversial New York Times report, the person is “a CIA officer who was detailed to work at the White House at one point, according to three people familiar with his identity.” He has since returned to the CIA.

The whistle-blower’s attorneys refused to confirm these details, and said publishing them is dangerous.

“Any decision to report any perceived identifying information of the whistle-blower is deeply concerning and reckless, as it can place the individual in harm’s way,” said Andrew Bakaj, his lead counsel. “The whistle-blower has a right to anonymity.”

Could Trump’s actions — or his administration’s — be illegal?

Trump pressuring a foreign leader to produce dirt on a political rival could be a campaign-finance-law violation. But as former federal prosecutor Renato Mariotti argued in Politico prior to the transcript’s release, “it is a kind of corrupt conduct that the criminal system is not equipped to handle.”

A bribery charge wouldn’t hold up in court, Mariotti explains, because offering military aid for a foreign investigation of a political opponent’s son doesn’t line up with the federal bribery statute, and extortion won’t hold up either, because “courts won’t send presidents to prison for cajoling foreign governments to do things, even if that involves horse trading an official act by our government in exchange for an official act by someone else’s.”

Mariotti makes it clear that impeachment is the only recourse designed to address a transgression of this scale. As New York’s Ed Kilgore notes, the president does not have to commit a crime to be impeached:

Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution specifically mentions “treason” and “bribery” as grounds for impeachment, but it also stipulates that “other High Crimes and Misdemeanors” are sufficient. It’s important to understand that when the Constitution was adopted, the term “misdemeanors” had not assumed its later meaning as a type of criminal offense. According to the most common interpretation of this language, impeachment does not require the allegation of a crime, but simply some grave act or pattern of misconduct deemed by Congress as necessitating this radical remedy.

How has Biden responded?

Last week, the Democratic front-runner called for the release of the president’s phone-call transcript, saying “If these reports are true, then there is truly no bottom to President Trump’s willingness to abuse his power and abase our country.” Later that day, his campaign turned the issue into a fundraising opportunity, emailing supporters:

Eight. That’s how many times Donald Trump asked a foreign leader to investigate me and my family. It’s more clear than ever: We’re in a battle for the soul of this nation. And now, I need you — right now. Can I count on you to donate tonight?

On the campaign trail in Iowa on Sunday, September 22, Biden called for an investigation into Trump’s conduct, adding that he has “never spoken to [his] son about his overseas business dealings.”

Is there a Russia connection?

Though it does not appear that there is a direct link to the Kremlin, the president’s alleged Ukrainian meddling certainly benefits Russian interests — particularly if the July phone call had anything to do with the August slow-walking of military aid to Ukraine. And as journalist Julia Davis notes, any news cycle that makes Ukraine and the U.S. look bad is a double win for Russia, as its two foes become mired in controversy.

This post has been updated throughout.

More on the Trump-Ukraine Scandal

- Trump’s Impeachment Trial and the Verdict of History

- Trump Fires Impeachment Witnesses Alexander Vindman and Gordon Sondland

- Trump Impeachment Hearing Schedule: What’s Next?