If America picked its presidents democratically, Democrats could sleep more serenely. In virtually every national poll of a hypothetical 2020 election, the Donkey Party’s top three primary contenders lead Donald Trump comfortably. CNN’s most recent survey finds Joe Biden beating Trump by ten points, Bernie Sanders besting the billionaire by nine, and Elizabeth Warren ahead by eight.

Other pollsters give Democrats a narrower advantage. And polling this far from Election Day is only a bit more reliable than an IOU from the Trump Organization. But the consensus of existing surveys is buttressed by broader data on demographic trends. Under the president’s leadership, the Republican Party has grown historically reliant on the support of non-college-educated white voters — at a time when non-college-educated whites make up a rapidly-declining percentage of eligible voters. With each passing year, America’s voting-age population grows less white, and its white voting-age citizens grow more learned. In 2020, there will be 2.3 percent fewer voting-age whites without a college diploma in the U.S. than there were in 2016, according to a new study from the Center for American Progress (CAP; a liberal think tank). Meanwhile, there will be 1.3 percent more Latino eligible voters, 0.6 percent more Asian eligible voters, and 0.2 percent more African-American and college-educated white ones.

Those percentages may look small. But in a body politic as closely divided as our own, even minuscule shifts in the electorate’s demographic composition can have world-historic consequences. If the 2020 election played out almost exactly like 2016 — with each demographic group turning out at the same rate, and each major-party candidate winning the same share of each demographic group’s ballots — the population changes projected by CAP would be sufficient to increase the Democratic nominee’s margin of victory in the popular vote by 1.2 percentage points. Which is to say: If the Democrats’ 2020 standard-bearer essentially replicates Hillary Clinton’s performance, he or she will would win the popular vote by 3.2 percent. Given the myriad improbable misfortunes that Clinton’s 2016 campaign suffered (and the candidate’s below-replacement skills as a retail politician), CAP’s data suggests that the next Democratic nominee shouldn’t have much trouble winning more ballots than Donald Trump.

But American presidential elections aren’t decided democratically. Winning more votes won’t get the Democrats very far if those ballots aren’t optimally distributed across state lines. And the emerging Democratic majority is so inefficiently distributed across space, Trump could plausibly win reelection while losing the popular vote by 5 percentage points.

The 2020 election will not be decided by eligible voters nationwide — but rather, in all probability, by actual voters in Wisconsin. As the chair of the Badger State’s Democratic Party, Ben Wikler, recently explained to Bloomberg, “If you take all the states where Trump is less popular than Wisconsin, that’s not enough to win the Electoral College. All the states where he’s more popular than Wisconsin, not enough to win the Electoral College. So whoever wins Wisconsin essentially will be president.”

In 2016, Trump won Wisconsin by just 22,748 votes. Hold all else constant — which is to say, freeze each major demographic’s turnout rate at its 2016 level, and keep the two-party share of each group’s vote steady — and the population changes projected by CAP would be enough to move the state into the Democratic column.

But as Bloomberg’s Francis Wilkinson reports, that’s an enormous “if.” Wisconsin is unusually white for a purple state in 2019. 87 percent of the Badger State’s population is Caucasian, according to Census Bureau estimates. In Pennsylvania, that figure is 82 percent; in Michigan, it’s 79 percent. And Wisconsin’s white population is less college-educated than the Keystone State’s. In demographic terms, Wisconsin is scarcely more favorable for Democrats than Ohio — which, in the Trump era, appears to have become a safe red state. Democrats owe their competitiveness in Wisconsin to two things: Its white population is unusually Democratic (an ostensible legacy of the state’s rapidly declining labor movement), and a lot of its white non-college-educated residents don’t vote.

But in the Trump era, those things might be changing. The mogul won the state in 2016 by, among other things, bringing a bunch of first-time white non-college voters into the electorate. And as Wilkinson notes, there’s a lot more where they came from:

You can register and vote in Wisconsin on Election Day. In three counties in this southwest corner of the state, each of which flipped from Democrat to Republican, same-day registration jumped from 2012 to 2016 — up 22% in Vernon County, up 40% in Crawford, up 54% in Grant. “They were in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, and they were farmers and they were mostly men,” Vinehout said of the new voters. “And they voted for Trump.”

… The universe of nonvoters is vast. Nationwide, 4 in 10 of those eligible did not vote in 2016. According to Brookings Institution demographer William Frey, more than 21 million nonvoters in 2016 were non-college-educated white men, Trump’s base. In Wisconsin, which is 81% non-Hispanic white, 459,000 non-college-educated white men didn’t vote in 2016. Trump won non-college-educated white men nationwide by an astounding 50 points. A modest rise in their turnout in key states in 2020 could swamp the Democratic nominee.

… Low-propensity voters tend to be low-information voters with weak or nonexistent ties to political institutions and limited interest in politics. But Trump has been politicizing every corner of American life, from consumer brands to social media and even football. With politics inescapable, how many more nonvoters might join the fray?

This week, a Marquette Law School poll of Wisconsin found Biden leading Trump by six points in the state, while Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both led him by two. Only Biden’s lead is outside the poll’s margin of error. And a sharp spike in the voter-participation rate of Wisconsin’s missing non-college white male voters could be enough to break Marquette’s turnout model, and swallow all the Democratic candidates’ leads.

Still, Democratic operatives don’t need to start popping Xanax like Tic Tacs just yet. Wilkinson’s nightmare scenario is plausible. But it’s also far from probable, for (at least) three reasons:

1) If Trump’s full-spectrum politicization of daily life triggers a turnout surge in Vernon County, it will probably do the same in Milwaukee and Wisconsin. The president’s myriad, wildly irresponsible attempts to mobilize his base in 2018 succeeded on their own terms. Non-college white voters turned out at unusually high levels for a midterm — but so did college-educated whites and minority voters. To be sure, there are more “missing” working-class white voters in Wisconsin than there are “missing” voters from those other demographic groups. But there’s also some reason to think that Democratic-leaning constituencies are likely to see a larger spike in their turnout rates than Trump-supporting ones. After all, as of November 8, 2016, Trump had already been inundating the national psyche with his brand of white-grievance politics for more than a year. To the extent that his message has a magical mobilizing potential, it was already an operative factor in 2016. Trump’s access to the bully pulpit may enhance his capacity to reach disaffected white nonvoters. But the fact that he no longer lays claim to the status of “change candidate” could also blunt his appeal with that constituency.

Meanwhile, for Democrats, 2016’s political climate was peculiarly inauspicious for rallying its least-reliable supporters. Hillary Clinton’s historic unpopularity, James Comey’s indefensible reopening of the investigation into her email server — and the widespread perception that Trump simply could not win — all served to undermine Democratic get-out-the-vote efforts. It’s possible that Trump will succeed in dragging the Democratic nominee’s approval rating down to Clinton’s level, and that Bill Barr will generate some untimely legal problems for blue America’s standard-bearer. But, at the very least, this time around, there will be little doubt in Democratic voters’ minds that Donald J. Trump can actually win a presidential election in the United States.

2) Donald Trump isn’t as popular with white non-college voters as he used to be. Juicing turnout among white non-college voters will do the president little good if his advantage with the demographic sharply declines. And the available polling data suggests that it might. Wilkinson’s nightmare scenario focuses on white working-class men for a reason — their female counterparts have soured on the misogynist-in-chief. As The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein wrote in late July:

Trump’s job-approval rating on Election Day 2018 among [white working-class women] stood at just more than 50 percent in [Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin] … In each state, that represented a decline of about five percentage points from his share of their vote in the presidential election. That’s not a radical shift, but in three states that were decided by a combined 78,000 votes in 2016, it could have a powerful impact.

National polls since the 2018 election have continued to show Trump facing a cooling reception from these women. Both the latest NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, released early last week, and the NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll released this week show him with a net-positive approval rating of just seven percentage points among blue-collar women, well below his vote advantage in 2016. The Marist poll found them divided almost exactly evenly on whether they intend to vote for or against Trump for reelection.

Is it possible that Trump’s 2020 campaign could bring (historically nonvoting) white working-class men to the polls in droves — while the women in their lives mostly stay home? Sure. But given that, in the aggregate, women vote at higher rates than men, I imagine Democrats would be happy to take the other side of that bet.

3) Democrats can gain a lot of ground without turning out a single new voter, or changing a single Trump supporter’s mind. Among the many lucky breaks Trump caught in 2016 were the candidacies of Gary Johnson and Jill Stein. In Wisconsin, the two third-party candidates collectively laid claim to 137,746 votes that year — a sum more than six times larger than Trump’s margin of victory in the state. By contrast, in 2012, the Libertarian and Green Party candidates won a combined 28,104 of the state’s votes.

One might question whether the surge in third-party voting redounded to Trump’s benefit. After all, wouldn’t the Libertarian ticket’s rise come at the GOP’s expense? But the available evidence suggests that, in the aggregate, 2016 third-party voters leaned left. Furthermore, for a candidate as unpopular as Trump was in 2016 — and is all but certain to be in 2020 — anything that lowers the percentage of the vote necessary for securing a statewide plurality is likely to be more helpful than not.

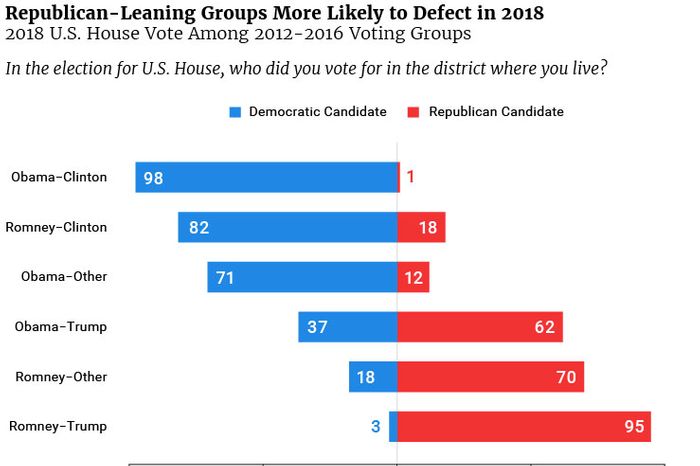

Happily, the Voter Study Group’s tracking poll suggests that Democrats have a very good shot of bringing its wayward sheep back into flock next year (assuming Tulsi 2020 doesn’t become a thing, anyway):

None of this is to say that Democrats shouldn’t feel a little pinprick of anxiety every time they see a Packers jersey, block of Cheddar, or other reminder of the Badger State’s existence. Wisconsin is balanced on a knife’s edge. There are plenty of ways Trump could win the state without generating an improbable one-sided turnout surge. But the things that could go wrong aren’t any more likely to happen than those that could go right — especially if Democrats keep up the fight.