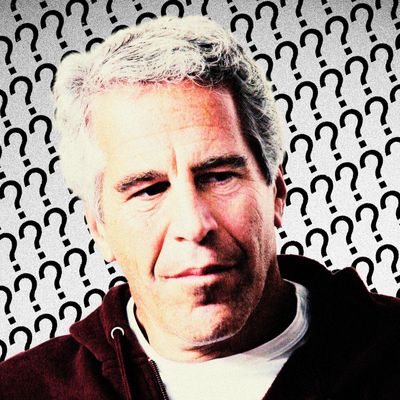

In the past two months, the swarm of conspiracy theories surrounding Jeffrey Epstein’s death has not dissipated, despite New York City medical examiner Barbara Sampson’s conclusion that he killed himself, alone in his cell, early on the morning of August 10. Two in three Americans doubt the results of the official autopsy, a high but perhaps unsurprising figure, considering America’s generally paranoid mood these days, and the legitimately odd circumstances of Epstein’s death. Why, following an alleged attempt to kill himself on July 23, was Epstein taken off suicide watch after just six days? How could he have hung himself from the top bunk when the prison’s bedsheets are as thin as paper? And how did a camera outside his cell happen to fail at the same time that two guards in his unit fell asleep, providing an unobserved window for whoever killed Epstein to kill Epstein?

Skepticism about the official cause of Epstein’s untimely end isn’t confined to Twitter or gossipy co-workers trying to avoid talking Trump. In court, Epstein’s defense team said they have “significant doubts regarding the conclusion of suicide.” They argued that resolving the questions surrounding Epstein’s death is vitally important, both to ensure that conditions improve for inmates at Metropolitan Correctional Center and to bolster public confidence in the legal system. Plus, said attorney Martin Weinberg, “we deeply want to know what happened to our client.”

That is no doubt true — but like all aspects of the Epstein case, this point is tangled and complicated, and there are lots of angles for insiders to play.

Here’s a closer look at what factors — practical, strategic, and otherwise — might be motivating Epstein’s attorneys to challenge the official story about his death.

Possible Explanation No. 1: Epstein’s Attorneys Truly Doubt That the Facts Point to Suicide

During a hearing in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on August 27 — which was convened to consider the prosecutors’ request to drop the sex-trafficking charges against Epstein, and give his alleged victims an opportunity to speak — defense attorneys Reid Weingarten and Martin Weinberg called for a court investigation into their client’s death, citing several details that cast doubt on the suicide ruling.

Noting that they had their own doctor observe medical examiner Barbara Sampson’s autopsy, Weinberg said, “We are told by a very experienced forensic pathologist that the broken bones in Mr. Epstein’s neck, his larynx, are more consistent with external pressure, with strangulation, with homicide if you will, than with suicide.” (Pathologist Michael Baden, who testified for O.J. Simpson’s defense, observed the autopsy for the defense, but he wasn’t cited by name at the hearing.) Weinberg acknowledged that these findings don’t “exclude suicide,” but he said they raise “profound issues” about what happened to Epstein. On October 30, Baden further muddled the picture of Epstein’s death, when he told Fox & Friends “that the evidence points to homicide rather than suicide.”

In court, the lawyers also asserted that suicide doesn’t square with their client’s state of mind in the days before his abrupt passing. “At or around the time of his death, we did not see a despairing, despondent, suicidal person,” Weingarten said. Epstein had reason to be hopeful: His attorneys were on the verge of filing what they considered an ace-in-the-hole motion, which would argue that his non-prosecution agreement in Florida was “global” and could override the new sex-trafficking charges in New York. “We had a significant motion to dismiss,” Weinberg said. “This was not a futile, you know, defeatist attitude.”

In the New York Post, a source “familiar with the case” went even further, claiming Epstein was in “great spirits” in the week before his death and that he told a lawyer on Friday — the day before he was found in his cell — “I’ll see you Sunday.” The financier had so much confidence in his team’s pending motion that he seemed “delusional,” according to the source.

Possible Explanation No. 2: Epstein’s Attorneys See a Natural Partnership With Victim Representatives in Seeking an Investigation

“Talk about a yikes,” Weingarten remarked in court on August 27, describing multiple reported failures by MCC staffers. “We have heard allegations that people at the time who had responsibility for protecting our client falsified information,” he said. “We understand that there were orders out there that Jeffrey Epstein was never to be left alone and that the orders were ignored by many employees of the prison.”

The attorney said the “800-pound gorilla” for the defense is the lack of usable video footage from around Epstein’s cell, and questions about how long this “stunning incompetence” had gone on. Had the system been out for six months, or did it fail shortly before Epstein arrived? And “what if the tapes only broke down or were inoperative or were corrupted on the day he was killed or the day he died?” Weingarten mused. “Then we’re in a completely different situation.”

Weingarten alleged that in general, conditions at MCC are “dreadful” — “not just for Jeffrey Epstein, but for many of the prisoners over there.”

The defense argued that the court should step in to get to the bottom of these issues — whether by holding hearings or assigning a lawyer to look into them — though there are already several ongoing federal investigations into Epstein’s death. Weingarten said that while the defense has “complete confidence” in prosecutors from the Southern District and the FBI, “these are allegations against serious components of the United States Department of Justice. Sometimes the appearance of justice is just as important as justice itself.” Court supervision is key “for the public to have confidence in the ultimate findings.”

This request was quickly shot down by Assistant U.S. Attorney Maurene Comey, one of three lead prosecutors in SDNY’s case against Epstein. (She is the daughter of James Comey, the former FBI director central to that other vast international scandal.) Maurene Comey argued that a separate investigation “into uncharged matters,” like the manner of Epstein’s death, is not in the purview of the court.

But the request for a court investigation is one of few points of agreement between the defense and some of Epstein’s alleged victims. Gloria Allred, who appeared at the same hearing representing five women who claim to have been abused by the financier, told New York that such a probe is essential “because the system has failed in such a glaring way to provide justice for the victims and real accountability for Epstein.” Allred, whose clients include alleged victims of R. Kelly and 33 women who accused Bill Cosby of sexual assault, added, “I don’t think that it ends” at the suicide determination. “Ordinarily it might, but because of the massive breakdown in this system, I think that the only neutral option would be the court.”

Possible Explanation No. 3: Suicide Complicates the Epstein Attorneys’ Legal Task

Even though Epstein is dead, many of the legal cases against him are not, and his attorneys will continue to represent the interests of his estate. In this context, there could be a compelling legal reason for the defense to cast doubt on a suicide determination. NYU School of Law professor Stephen Gillers notes that suicide can be “introduced in court to show consciousness of guilt amounting to a confession.” There is precedent in New York as well: In the 2016 case People v. Matthews involving an appellate opinion in which the defendant was convicted of sexual conduct against a child, the Court “admitted evidence concerning [the] defendant’s suicide attempt, including his suicide note, as relevant to his consciousness of guilt in prosecution.”

It’s possible that Epstein’s accusers will pursue this avenue, arguing that his suicide equates to an awareness of his guilt. Overturning the suicide determination could preempt this strategy, leaving the attorneys tasked with defending Epstein (or, following his death, preserving what’s left of his fortune) with a simpler — but still difficult — task.

Possible Explanation No. 4: Challenging the Suicide Ruling Could Prove Profitable for Epstein’s Attorneys (and Others)

The will Epstein signed two days before his death put the value of his estate at $577 million — not including his art collection. But the suicide ruling may be a factor in how much money is ultimately available to Epstein’s currently unidentified heirs, people owed compensation, and his alleged victims. Epstein’s attorneys, of course, are obliged and motivated to work in the interests of the estate, which includes maximizing its assets.

“Some life-insurance policies do not pay if the person has committed suicide — as opposed to if they were murdered,” notes Elie Honig, a white-collar defense attorney, former federal prosecutor, and CNN legal analyst. There’s no public information on whether or not Epstein had life insurance, but it’s common for high-net-worth individuals to buy policies. According to one wealth management consultant, life-insurance policies are often required for the profoundly wealthy to obtain loans (although Epstein’s path to riches didn’t involve a lot of conventional borrowing). The ultrarich are not always liquid, so life-insurance payouts can help cover big-ticket postmortem costs — like, say, paying elite white-collar attorneys to defend one’s estate against claims from scores of young women and children.

Getting to the bottom of MCC’s failures could have side benefits for everyone seeking payment from Epstein’s estate. “It is possible that the Epstein estate may assert a claim against the jail for negligent supervision,” Gloria Allred proposed. “If circumstances of death result in successful claims by the estate against the jail, that could result in additional funds going into the estate that in turn could be potentially available to victims to file lawsuits and prove claims.” An eventual win in that motion could mean a handsome payday for Epstein’s lawyers.

Bradley Edwards, the Florida attorney who has represented several Epstein accusers since as early as 2005, nodded at this possibility during the August 27 hearing, saying that while no one was pleased by the defendant’s passing, if it’s determined that “there is some civil-rights violation and there is some civil remedy for Mr. Epstein that goes into the estate, certainly the victims are interested in that as they might help to repair the damage done.”

Martin Weinberg acknowledged, in a statement to New York, that the defense could pursue such a suit, but he suggested it would be for moral, not just monetary, reasons. “If we bring a federal lawsuit against the MCC, it is as much about principle as money,” he said. “No one should die in jail, and any lawsuit would be seeking to determine who was responsible for Mr. Epstein’s death as well as for the horrific conditions in which he was detained.”