Young people who do not go to college tend to be more economically disadvantaged than those who do. This is not solely a function of rising tuition costs. For one thing, the peripheral costs of college attendance — from lost wages to books to housing — are often more formidable obstacles for working-class kids than tuition. For another, children from low-income households are not merely less likely to attend a university, but also, to be eligible to attend one, due to class disparities in high-school graduation rates. Separately, Americans who do have the opportunity to attend college generally enjoy higher incomes and living standards later in life than those who do not.

The U.S. economy does not have an insatiable demand for college-educated labor. According to federal projections, most of the fastest-growing occupations in the U.S. do not require a four-year degree. This means that we need a significant percentage of our young people to accrue forms of knowledge, skill, and experience that colleges aren’t designed to provide. If young Americans with little interest in — or aptitude for — higher education did not exist, we would need to invent them.

Given these realities, one can reasonably argue that tuition-free college should not be a priority of the progressive movement. To the extent that the next Democratic president’s capacity to enact new laws is constrained by Congress’s legislative calendar and moderates’ limited appetite for new spending, there will ostensibly be more progressive things for him or her to spend $70 billion on than a social benefit that America’s most disadvantaged young people are ineligible for, almost by definition.

On the other hand, this same basic logic could have been deployed in opposition to tuition-free 12th grade a generation ago (after all, the most disadvantaged students drop out before senior year). If we believe that the value of public education isn’t limited to its function as a generator of human capital or labor-force readiness — and thus, that it does not merely benefit its direct recipients but also, society as a whole — then the distributional implications of tuition-free college don’t necessarily matter. (In my own view, the growing correlation between college-degree attainment and immunity to xenophobic nationalism strengthens the case for seeing higher education as a broad social good.)

And anyway, as Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project has argued, there are ways to integrate free public college into a more inclusive, universalist program for helping young adults refine their skills and attach to the labor force:

[W]e should as a society designate ages 18–24 as the attachment zone during which all paths into a career are fully supported by public benefits and services. Students get their free school. But, under the exact same umbrella, nonstudents get their free vocational training, subsidized apprenticeships, in-work subsidies, public jobs, and whatever else it takes to ensure a lasting labor force attachment. That would be a program that is actually in fitting with the ideals of universalism.

All of which is to say: There are worthwhile intra-Democratic debates to be had over tuition-free college, including ones that interrogate its distributional impacts.

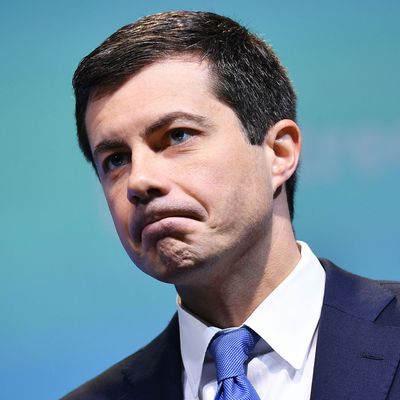

But Pete Buttigieg’s latest broadside against the policy is not one of them:

The serious distributional critique of free college is not that it would benefit the children of “billionaires,” but that it would deliver less benefit to the poor than it would to the upper-middle class. But the upper-middle class is Mayor Pete’s core constituency. And so, his campaign has chosen to argue that the only thing preventing the superrich from flooding our public universities with their progeny is the exorbitant cost of out-of-state tuition.

Now, if Pete had restricted his complaint to millionaires, he’d have something closer to a point. (Many upper-middle-class families do own more than $1 million in assets.) According to the Roosevelt Institute’s Mike Konczal, children whose parents are in the top one percent of earners would commandeer a whopping 1.4 percent of spending on tuition-free college. It’s hard to see why that sum should be a dealbreaker, especially if the policy is funded with higher taxes on the rich. Still, it isn’t literally nothing.

If Konczal restricted his estimates to billionaires however, it would be pretty darn close to zero percent. There are just over 600 billionaires in the entire United States, and they are not known for sending their kids to public schools. At present, the average cost of out-of-state tuition at a public university in the U.S. is $25,000. As a percentage of one’s spending power, $25,000 is for a (low-digit) billionaire what one movie ticket is for the median American household. It’s ludicrous to think that making public college tuition-free would cause billionaires to send their kids to public universities in droves, especially when one considers that once public higher education is tuition-free, a public-college diploma will be an even weaker marker of elite status than it already is.

And yet, the biggest problem with Pete’s fear of Americans’ footing the bill for the college-bound children of billionaires may be this: If it were actually true that making public college tuition-free would cause billionaire trust-fund kids to start sharing classrooms and social circles with working-class adolescents, that would make the case for tuition-free college stronger. After all, reams of educational research has shown low-income students derive massive benefits from attending schools with more privileged peers. Redistribute billionaire children from selective private colleges to public universities, and you’ll have progressively redistributed large sums of social capital, while rendering America’s institutions of higher education more socioeconomically diverse. Pete Buttigieg, of all people, should see the virtue in that outcome: After all, the South Bend Mayor has proposed a national service program aimed at getting America’s young people out of their “distinct bubbles.”

Tuition-free public college won’t deliver much of any benefit to the children of billionaires. But it would be an even more worthwhile program if it did.