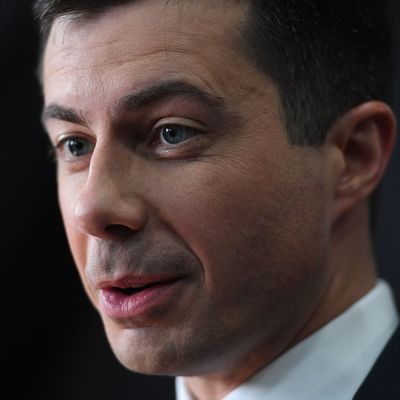

After he emerged unscathed from a presidential candidates’ debate in Atlanta, where many expected him to become a piñata, South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg is heading toward the holidays in an enviable position in Iowa and New Hampshire polls. He appears to have plenty of money, a solid organization, and a degree of popularity that is likely to improve as he becomes better known (according to Morning Consult, 39 percent of Democratic primary voters don’t know enough about him to form an opinion). And it’s entirely possible that six of his rivals will be spending crucial days leading up to the early-state contests stuck in Washington in an impeachment trial with constraints on their ability to speak freely.

It is probably time, then, to think seriously about this unlikely candidate as a potential challenger to Donald Trump. To ask the slippery but inevitable question that anxious Democratic voters appear to keep in the back (if not the front) of their minds, is Mayor Pete electable?

For those who place faith in early head-to-head polls (which have a shaky reputation for reliability), there’s limited relevant data, since Buttigieg wasn’t often tested against Trump until recently. He has a 2.8 percent advantage over the president in the RealClearPolitics polling averages (not that impressive compared to Biden’s 9.6 percent edge, or Sanders’s 7.9 percent, or Warren’s 6.8 percent). But his relatively low name ID may artificially depress his numbers. Political scientist Robert Griffin estimates that Buttigieg’s six-point matchup advantage over Trump in one poll would jump to ten percent if he became as well-known as the Big Three.

Concerns about the mayor’s electability, though, are less about numbers than about questions concerning the coalition of voters he might or might not put together. Ironically, the candidate whose rhetoric and ideology are strikingly reminiscent of the 44th president’s has generated more skepticism than any of his rivals in terms of reviving the Obama coalition that once seemed to promise Democrats perpetual victory.

Despite his youth — which he emphasizes regularly on the campaign trail — Buttigieg isn’t notably lighting up young people. A new Civiqs poll of Iowa that shows him with a solid overall lead also shows him trailing septuagenarians Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren among under-35 voters, while he leads the field among seniors.

Buttigieg’s overwhelmingly white base of support has gotten a lot of attention. In a recent Latino Decisions poll of California Latinos, he came in at one percent, a point behind Andrew Yang. And his inability to attract African-American support is becoming even more conspicuous as his strength in mostly white places like Iowa and New Hampshire grows. Whether you think his problem in this demographic stems from the problems he’s had in South Bend with police-minority relations, or from his sexual orientation, or from his general “wine track” political style, it’s real, and it presents a real obstacle in his path to the nomination — particularly when the majority-black electorate in South Carolina weighs in on February 29. A new Quinnipiac poll of the Palmetto State released earlier this week gives Buttigieg a flat zero percent among black voters. And here’s how Reid Epstein summarizes the mayor’s visible black supporters:

Mr. Buttigieg has so few black elected officials and former elected officials backing him that they could all fit into a single S.U.V. The issue emerged during a meeting he held this summer with Congressional Black Caucus members who pressed him about why he did not have black officials from South Bend vouching for him on the campaign trail.

Of the black elected officials and former elected officials who have endorsed him, only Sean Shaw, a former one-term Florida state representative who lost his statewide race last year, has been to South Carolina on his behalf.

The vibe could soon get worse:

Our Revolution, a political organization backing Mr. Sanders, is planning a Dec. 7 rally in South Bend that will highlight Mr. Buttigieg’s handling of the June police shooting and feature a black South Bend Common Council member aggrieved that two of her properties were razed by Mr. Buttigieg’s municipal government.

Putting aside the impact of Buttigieg’s narrow band of support on what you might call his “nominatability,” though, does it mean he would lose a general election to the likes of Donald Trump? That’s hard to say.

Without question, Democrats are counting on minority-voter enthusiasm in 2020, and having a nominee who leaves black and brown voters cold could be a serious problem, particularly in the Rust Belt states where mediocre black-voter turnout was a factor in Hillary Clinton’s shocking 2016 loss. But then again, after three years of the racist stylings of the president, African-Americans may not need much motivation to turn out to smite him next year. As Frank Newport of Gallup noted this week, Trump’s job approval rating among black voters has been stuck at 10 to 11 percent since his inauguration, a number likely to produce a general-election showing in the single digits. If Trump decides, as is likely, to rev up his base with some unusually crude appeals to white identity politics, Buttigieg’s black enthusiasm problem could vanish. It’s also likely that Mayor Pete’s ambitious “Douglass Plan” for black empowerment, which has so far failed to move primary voters in his direction, would look much better to African-American voters in the context of a general-election contest with Trump.

It’s even more likely that the progressive activists who are currently expressing hostility to Buttigieg would come around. Much as they dislike Medicare for All Who Want It, it’s infinitely preferable to such Republican policy wish-list items as privatizing Medicare, repealing Obamacare, and radically cutting Medicaid.

In the end, though, a vote’s a vote, and the real question is whether Buttigieg could reach enough voters other potential nominees would miss to offset some turnout gaps. In that vein, his regional appeal is certainly germane to his competitiveness in those same Rust Belt states that Clinton lost. And the very wine-track style that creates problems with some voters may attract others — particularly those Republican-leaning suburbanites who helped Democrats retake the House last year.

One unavoidable question about Buttigieg is whether being the first openly gay major-party presidential nominee would be a net positive or negative. It’s almost impossible to calculate. The percentage of Americans saying they would be fine with a gay president is steadily rising, but a recent Morning Consult survey showed 37 percent weren’t ready for it. Recognizing that a solid majority of such voters probably wouldn’t vote for any liberal, it’s simply not clear whether the “backlash” to Buttigieg’s sexual orientation would exceed the “frontlash” from voters, including LGBTQ voters, pleased to break this particular barrier. And regardless of objective reality, yet another “nominatability” problem for Mayor Pete is that risk-averse Democrats might not want to test the proposition in this particular cycle, when a second Trump term is the punishment for guessing wrong.

If Buttigieg does, against the odds, become the Democratic presidential nominee in Milwaukee next July, he would be in a position to campaign as the ultimate un-Trump: progressive where Trump is reactionary; multilingual where Trump is barely literate in English; a meritocrat running against a great symbol of inherited privilege; a vet opposing a draft dodger; an observant Christian exposing the shallow belief system of a philistine and heathen. And in fact, that’s a context in which Buttigieg’s Obama-style rhetoric of unity and uplift might strike some sparks, instead of just reminding those who affectionately harken back to Trump’s predecessor of what the country has lost.