In late August, a black-sailed ship appeared in the harbor carrying a 16-year-old visionary, a girl who had sailed from the far north across a great sea. A mass of city-dwellers and travelers, enthralled by her prophecies, gathered to welcome her. She had come to speak to the nations of Earth, to castigate us for our vanities and warn us of coming catastrophe. “There were four generations there cheering and chanting that they loved her,” the writer Dean Kissick observed. “When she came ashore, it felt messianic.”

I can’t have been the only person who felt, when Greta Thunberg made landfall in New York City in late summer, as though I were living, strangely, through the early pages of a fantasy epic. For most of my life, the paradigm for imagining the future has been dystopian science fiction: In every photo of a gleaming neon city, in every story of advanced and ruthless cyberwarfare was reflected the ultramodern, hyper-capitalist visions of cyberpunk writers like William Gibson, whose work was so influential it shaped how the early architects of the internet understood their creation. But where would a schoolgirl prophet sailing from the frozen north to confront the kings and queens of a planet fit in to the high-tech noir I had been taught to expect? Which tale of corporate cyber-intrigue contained a visionary leading a child army in marches across the globe?

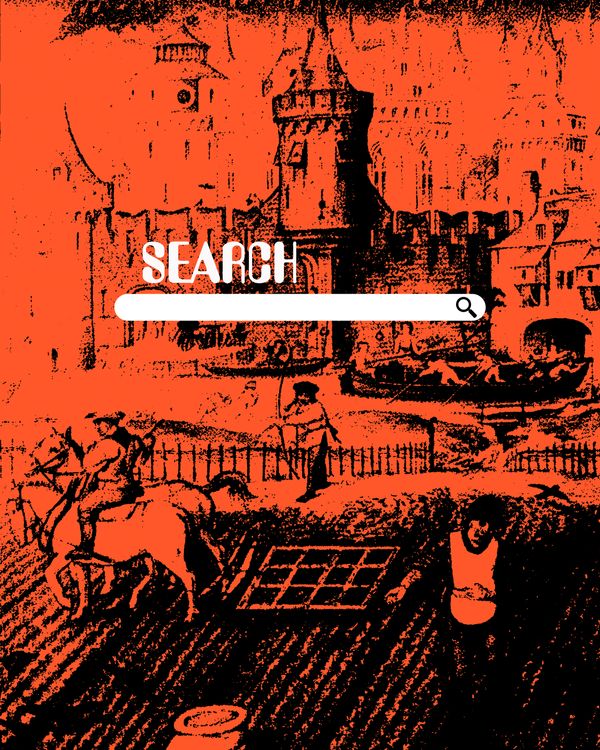

Looking around lately, I am reminded less often of Gibson’s cyberpunk future than of J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantastical past, less of technology and cybernetics than of magic and apocalypse. The internet doesn’t seem to be turning us into sophisticated cyborgs so much as crude medieval peasants entranced by an ever-present realm of spirits and captive to distant autocratic landlords. What if we aren’t being accelerated into a cyberpunk future so much as thrown into some fantastical premodern past?

In my own daily life, I already engage constantly with magical forces both sinister and benevolent. I scry through crystal my enemies’ movements from afar. (That is, I hate-follow people on Instagram.) I read stories about cursed symbols so powerful they render incommunicative anyone who gazes upon them. (That is, Unicode glyphs that crash your iPhone.) I refuse to write the names of mythical foes for fear of bidding them to my presence, the way proto-Germanic tribespeople used the euphemistic term brown for “bear” to avoid summoning one. (That is, I intentionally obfuscate words like Gamergate when writing them on Twitter.) I perform superstitious rituals to win the approval of demons. (That is, well, daemons, the autonomous background programs on which modern computing is built.)

This strange dance of ritual and superstition will become only more pronounced over the next decade. Thanks to ubiquitous smartphones and cellular data, the internet has developed into a kind of supernatural layer set atop everyday life, an easily accessible realm of fearsome power, feverish visions, and apocalyptic spiritual battle. The medievalist Richard Wunderli has described the world of 15th-century peasants as “enchanted” — “bounded by a mere translucent, porous barrier that led to the more powerful realm of spirits, devils, angels, and saints,” which doesn’t sound altogether different from a world in which a literally translucent barrier separates me from trolls and daemons and pop-star icons into whose Twitter mentions and Instagram comments I might make quasi-religious pilgrimage.

The structure of the internet is headed toward an arrangement the cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier calls “digital feudalism,” through which the great landlords, platforms like Google and Facebook, “are becoming our feudal lords, and we are becoming their vassals.” We will provide them with the data-fruits of our browsing, in a nominal exchange for vague assurances of their protection from data-breach marauders. The sense of powerlessness you might already feel in the face of a megaplatform’s opaque algorithmic justice — and the sense of mystery such workings might engender — would not have seemed so strange to a medieval peasant. (Once you explained, you know, what an algorithm is.)

And as the internet bewitches more everyday objects — smart TVs, smart ovens, smart speakers, smart vibrators — its feudal logic will seize the material world as well. You don’t “own” the software on your phone any more than a peasant owned his allotment, and when your car and your front-door lock are similarly enchanted, you can imagine a distant lord easily and arbitrarily evicting you — with the faceless customer-service bots to whom you’d plead your case being as pitiless and unforgiving as a medieval sheriff. The Financial Times’ Izabella Kaminska suggests that, within the “frightfully medieval problem” of the sharing economy’s quasi-feudal control of its contractors, there’s “potential for the return of the guild structure”: Rideshare drivers, for example, might someday create an independent credentialing body to ensure portability of data and reputation across the “borders” of “landholders” (that is, Uber and Lyft), just as craftsmen might have used a guild membership to demonstrate their credentials early in the last millennium.

Where would this feudally arranged, spiritually charged layer of magic take our politics and culture? We could look to our president, who wields power like an absolutist king or a dodgy pope and who speaks, as many observers have noted, like a Greek hero or an Anglo-Saxon warlord — that is, in the braggadocious, highly repetitive style of the epic poetry characteristic of oral cultures.

Paradoxically, the ephemerality — and sheer volume — of text on social media is re-creating the circumstances of a preliterate society: a world in which information is quickly forgotten and nothing can be easily looked up. (Like Irish monks copying out Aristotle, Google and Facebook will collect and sort the world’s knowledge; like the medieval Catholic church, they’ll rigorously control its presentation and accessibility.) Under these conditions, memorability and concision — you know, the same qualities you might say make someone good at Twitter — will be more highly prized than strength of argument, and effective political leaders, for whom the factual truth is less important than the perpetual reinscription of a durable myth, will focus on repetitive self-aggrandizement.

All this, of course, will happen against the backdrop of disaster: a ruinous, volatile natural world, alien and unpredictable in its force and violence. Weather is becoming more difficult to forecast, and the effects of climate change have thrown into doubt the exhaustive knowledge that made the world familiar and governable. Nature appears to us in annihilating storms, raging fires, and epic floods, a literal manifestation of our earthly sins. Stuck in a preliterate fugue, ruled by simonists and nepotists, captive to feudal lords, surrounded by magic and ritual — is it any wonder we turn to a teenage visionary to save us from the coming apocalypse?

*A version of this article appears in the November 11, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From the Future Issue

- What Life in 2019 Can Tell Us About Life in 2029

- In 2029, It’ll Be Harder to Write Science Fiction Because We’ll Be Living It

- In 2029, I Will Worry About the Wind

- In 2029, IRL Retail Will Live Only Inside Amusement Parks

- In 2029, AI Will Make Prejudice Much Worse

- There Will Be No Turning Back on Facial Recognition