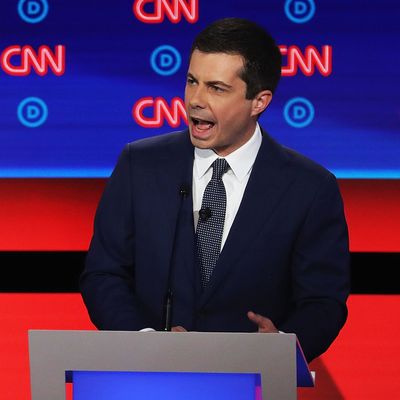

You can understand why Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar is annoyed by the relative success on the presidential campaign trail of South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg. She’s easily won three Senate races in a state that’s been trending Republican. Buttigieg has twice been elected mayor of the 306th largest city in America. She’s the next-door senator to Iowa Democrats. Pete’s town is more than 400 miles from Des Moines. Klobuchar’s claim to represent the Democratic mainstream against the dangerous lefty-progressives threatening to take over the party is based on an extensive Senate voting record. Buttigieg’s “fighting centrist” credentials are mostly a matter of assertion, and didn’t really emerge even in this campaign for a good while.

Yet Buttigieg leads Klobuchar in the RealClearPolitics polling averages for Iowa by 17.5 percent to 4.0 percent; for New Hampshire by 11.3 percent to 3.3 percent; and nationally by 7.0 percent to 2.6 percent. He’s raised a lot more money than Klobuchar: over $50 million so far in 2017, compared to her $18.8 million. Her explanation for this disparity seems pretty simple, and got some attention when she repeated it on CNN’s Sunday show this last weekend (as reported by the Washington Post):

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) said Sunday that women in politics are held to a higher standard than men, arguing that a female candidate with South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s experience probably would not make it to the presidential debate stage.

Klobuchar’s comments mark the latest instance of a 2020 presidential contender taking aim at Buttigieg, a newcomer on the national political stage whose ascent in the fundraising race and in polls for the Democratic nomination has taken many by surprise.

They also bring renewed attention to the hurdles female candidates face, following former vice president Joe Biden’s description last week of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) as “angry” and antagonistic.

As it happens, both Buttigieg and Klobuchar have already qualified for the November and December debates. So I guess in theory she’s not talking about herself but instead of some hypothetical woman. But Klobuchar also clearly wants to convey that she is being held to a double standard, too:

Klobuchar, who is on her third term in the Senate, described herself as “the one from the Midwest that’s actually won in a statewide race over and over again,” adding, “That’s not true of Mayor Pete.”

So the not-so-veiled suggestion is that Buttigieg’s success is principally the product of male (or perhaps white male) privilege.

Buttigieg has answered this charge earlier in the campaign, acknowledging his privileges but observing that it’s not the whole story of his candidacy, as Laura Bradley observed back in April:

[W]hen host Trevor Noah asked “Mayor Pete” whether he believes he’s benefited from white privilege, Buttigieg responded by acknowledging both that those privileges exist and that he’s considered that very question.

“I’d like to believe it’s my qualities and my message,” Buttigieg told Noah. “But I’ve been reflecting on this because one of the things about privilege, especially things like white privilege or male privilege, is that you don’t think about it very much. It’s being in an out-group where you are constantly reminded of it. It’s not when you are in a majority or a privileged group. And so, I try to check myself and make sure I try to understand the factors that help explain why things are going well.”

Pete probably didn’t have to say it out loud, but his other defense is that he, too, is a member of an “out-group” thanks to his gay sexual identity. So he’s not just some random vaguely centrist white male dude like Steve Bullock or Michael Bennet, whom Buttigieg is also trouncing in the polls, not to mention Beto O’Rourke, John Hickenlooper, Seth Moulton, or Tim Ryan, who have already dropped out. Each and every one of them had a better résumé than Pete, but that didn’t matter. And as a New York Times piece this week suggested, lots of candidates both resent and envy Buttigieg:

“It is a natural thing when a young candidate comes along and has success for other candidates who feel like they’ve toiled in the vineyards to resent it,” said David Axelrod, the chief strategist for Mr. Obama in 2008. “I think they’d like him better if he weren’t doing as well …”

Campaign aides acknowledge privately that Mr. Buttigieg triggers some of his rivals. But they dismiss the criticism as little more than sour grapes. Over last weekend in Iowa, he drew crowds of several hundred people in towns that numbered just a few thousand.

And it’s blind quotes like that which make other camps resent Mayor Pete even more.

Some observers assume Buttigieg’s sexual orientation is a handicap. But Gallup data show how rapidly that is ceasing to be an issue: Currently 83 percent of Democrats and 82 percent of independents (and even 61 percent of Republicans) deem themselves willing to vote for a gay or lesbian president, and the trend lines are clearly and quickly moving toward more acceptance of LGBTQ pols, and people generally. Meanwhile, being openly gay has pretty clearly helped Buttigieg raise money, as the New York Times reported in April:

After vaulting into the top tier of presidential candidates vying for the 2020 Democratic nomination — going from “adorable” to “plausible,” in his own words — Mr. Buttigieg is building on the fly a nationwide network of donors that is anchored by many wealthy and well-connected figures in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender political circles.

From more intimate cocktail parties on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where the composer Stephen Sondheim appeared in March, to larger events, like a planned June gala at the Beverly Hills home of the television producer Ryan Murphy, the L.G.B.T. donor base is helping push Mr. Buttigieg from the margins of the presidential contest into the same moneyed circles that raised millions of dollars for Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

Top L.G.B.T. donors face no shortage of loyal allies among the 20 Democratic candidates. But Mr. Buttigieg’s candidacy has struck an especially powerful chord with many of them. Though many said they believed they would see a gay man or lesbian become a serious contender for the White House one day, most of them had never considered it beyond the abstract. Mr. Buttigieg’s ascent has made a sudden and unexpected reality of something they thought was still years away, if not decades.

So Buttigieg’s sexual orientation is an “identity politics” credential for him that matters not just to LGBTQ folks, but to those who care about equality and breaking “glass ceilings.” Buttigieg would probably be the first to acknowledge that his claim to pioneer status is not as powerful as that of Barack Obama’s in 2008 (which the at time was resented by some feminists backing Hillary Clinton) or HRC’s in 2016. But it’s real, and the fact that he is married, religiously observant, and a military veteran adds a traditionalist twist to his background and identity which some voters likely find appealing — along with his much-discussed verbal skills. His youth, in an age-heavy field and in a party unusually dependent on millennial and post-millennial votes, is also an asset. And it’s worth noting that he didn’t exactly come out of nowhere: His well-regarded if unsuccessful 2017 race for DNC chair earned him a lot of good will, as Business Insider reported at the time:

John Verdejo had never heard of Pete Buttigieg before the Democratic National Committee chair’s race. By Saturday’s vote, he had only one impression of the South Bend, Indiana, mayor.

“Mind. Blown. Mind. Blown. You ask any of the DNC members here, and he was their second choice. I don’t care if you voted for Perez first, Ellison first — Buttigieg was their No. 2,” the North Carolina DNC member said here at the committee’s winter meeting in Atlanta.

None of this is to say that Buttigieg’s current position is stable, or fully earned. His “whiteness” is indeed an issue in the nominating contest, thanks to the trouble he has had dealing with police-minority relations in South Bend, and that may doom his candidacy when the contest moves past the very white states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

But the idea that Pete Buttigieg’s gender is the only reason anyone would prefer him to Amy Klobuchar a bit of a reach.

Now if Klobuchar was really arguing that a woman exactly like Pete Buttigieg — a married, lesbian, small-city mayor with military service who attends church and is unusually articulate about a more-or-less-centrist policy agenda – wouldn’t be doing as well as he is, thanks to media or voting bias or whatever — well, that’s a different proposition. But it’s not one we will get to test in 2020.