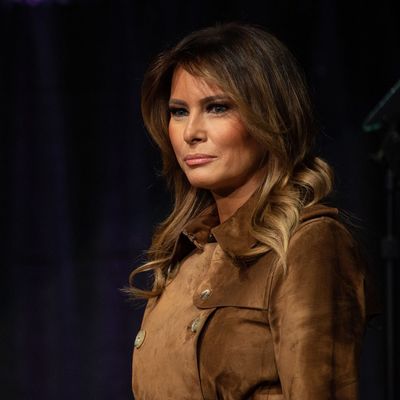

Melania Trump visited Baltimore on Tuesday to give a speech about opioid addiction, one of the pillars of her “Be Best” initiative, whose putative goal is to promote children’s well-being. Its other ambition is to address the scourge of cyberbullying among young people. The sincerity of the latter has long been in question; her husband’s presidency is nothing if not a test of America’s tolerance for ad hominem attacks on Twitter. When she took the stage, Trump was greeted with raucous boos from an audience of middle-school-aged children. The periodic jeers that followed interrupted her speech, in which she implored the kids to “reach out for support” or “talk to an adult in [their] life that [they] trust” if they’re fighting addiction. Underscoring their disdain is the fact that perhaps no grander illustration exists of the untrustworthiness of American grown-ups than the Trump White House, with its dismissal of climate science and policy of separating migrant children from their families. The First Lady weathered the cold reception and left in fine spirits anyway. She knew — as we all do — that she’s rich and powerful and will be fine.

My colleague Will Leitch has written at length about the sense of powerlessness that pervades the Trump era, the feeling that there’s little to be done to satisfactorily counter the president’s corruption and racism. Leitch has also written about the catharsis to be found in letting Trump and his family and representatives know how reviled they are to their faces, exemplified by the boos that greeted President Trump & Co. at a recent Washington Nationals baseball game. This no partisan phenomenon, either: Presidents Obama and Bush both faced their own jeers in public appearances.

But the first spouse-ship is unique in that its occupants often try to eschew politics. The relative lack of controversy around an initiative focused on children, as Melania Trump’s is, is by design a preferable alternative to something with more partisan baggage, like immigrant rights or racial inequality. There are notable exceptions, but a general consequence of their detachment is that first spouses tend to be among the most popular figures in their families, as has been the case with Trump, despite how she was received in Baltimore. They’re also the most susceptible to being defined by the traits, views, and politics the general public projects onto them. It is in this area that the differences between Trump and her predecessor, Michelle Obama, are most edifying.

Trump was not always seen as an ambassador for her husband’s politics. Beginning with his inauguration in 2017 and soon thereafter, there was a tendency among self-described “resistance” types to latch onto her every gesture of perceived rebellion as an occasion for plaudits — a smile to her husband’s face followed by a scowl once he turned his back; an apparent refusal to hold his hand; a photo of her lovingly appraising Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau with the president’s eyes downcast in a background sulk. These were countered by reminders that she’s an unrepentant birther, and repeated instances of her mirroring her husband’s bizarre fixation on the Obamas and warring with the media, like when she plagiarized one of Michelle Obama’s speeches, or when she wore a jacket to visit detained migrant children in McAllen, Texas, that read, “I don’t really care. Do U?” — an odd getup for visiting imprisoned toddlers by any measure, but equally strange as an attempted provocation to news outlets.

But if Melania Trump’s status as First Lady is defined by its inscrutability — and disagreements over whether she’s a sincere presidential surrogate or a #Resistance sleeper agent in need of emancipation — Michelle Obama’s was defined by racist backlash. For every O Magazine cover shoot celebrating what she meant for the social standing of black women, there was the county employee in West Virginia calling the former First Lady an “ape in heels,” the false rumors in right-wing media that she’d been videotaped using the pejorative “whitey,” and rants from Glenn Beck accusing her of “reverse discrimination” and “attacking white people” for discussing the impact of white flight on black communities. Rush Limbaugh famously derided a trip she took to Spain as “vacation affirmative action,” alluding to the gap between her lavish lifestyle and that of her enslaved ancestors. Laura Ingraham’s book The Obama Diaries ridicules her by depicting her devouring baby-back ribs at every meal.

Laid bare in both circumstances are the parameters of the American imagination. When presented with Melania Trump, her husband’s detractors have derided her in terms of whether she backs his policies — when they aren’t debating the extent to which her gestures and facial expressions mirror their own disgust toward him. But when Michelle Obama was First Lady, her husband’s opponents assailed her with an outsize focus on her blackness, mining racial stereotypes for humor and casting her as the personification of their paranoias about anti-white animus taking hold in the White House. If nothing else, both are potent illustrations of the first spouse-ship’s capacity for projection, and what happens when it’s used as a canvas onto which Americans can translate their anxieties. The outcome is telling: Both Michelle Obama and Melania Trump have their defenders, and have left or will leave the White House with perks, privileges, and lifelong security that most Americans couldn’t fathom. But one has the benefit of being assessed in terms of what she’s done. The other must contend with the knowledge that what made her objectionable to so many is that she’s black, in a country where white supremacy is routinely taken for granted.