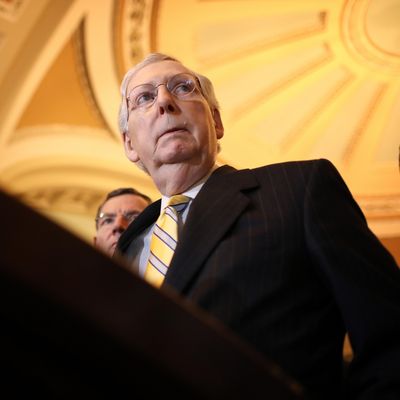

Now that the House has impeached President Trump on two counts, abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, attention will shift to the Senate, which is expected to try him (likely in January) and either acquit or remove him from office. Here’s everything we know about the trial, and what it might look like under Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

What Does the Constitution Say About an Impeachment Trial?

It’s helpful to understand that for both chambers, the U.S. Constitution doesn’t spell out a whole lot beyond specifying that the House has the “sole power” to impeach executive and judicial branch officials for “Treason, Bribery, and other High Crimes and Misdemeanors” and that the Senate has the “sole power” to remove impeached officials by a two-thirds vote if they are found guilty of such charges. The Founders also provided that for presidential impeachments the chief justice of the Supreme Court will be the Senate’s presiding officer, which was intended to avoid putting a vice-president, who might inherit the presidency if a removal did occur, in the chair. So in this case, we know Chief Justice John Roberts will preside over the trial. Beyond that, House and Senate rules, and ad hoc decisions made by the two chambers about matters not specified in the rules, decide pretty much everything.

Does the Senate Have to Hold a Trial If the House Impeaches Trump?

Constitutional authorities differ on this question, which is germane because Trump himself (and most recently his lawyer and co-conspirator Rudy Guiliani) keeps claiming that any House impeachment over the Ukraine scandal (and probably anything else) is “unconstitutional” or at least unwarranted. In theory, McConnell could agree with that assessment and refuse to hold a trial. And because the courts are extremely reluctant to intervene in “political questions” involving executive–legislative collisions, he might get away with it.

But in fact, McConnell has repeatedly said he would indeed hold a trial — too many times to reverse himself, in all probability, as the Hill reports:

“Under the impeachment rules of the Senate, we’ll take the matter up. The chief justice will be in the chair … We intend to do our constitutional responsibility,” he said.

McConnell had previously indicated that he would have “no choice” but to take up impeachment if the House passes articles, though he has also [run] a Facebook ad over the recent two-week recess positioning himself and the GOP-controlled Senate as a roadblock to Trump being removed from office.

Could the Senate Have a Perfunctory or Truncated Trial?

Again, McConnell has been talking as though there will be a real trial, but means are available to cut it short, as Democrats tried to do during the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton. Trump reportedly favored that strategy, initially, but in a November 21 meeting between White House representatives and Senate Republicans after two weeks of public testimony in the House, sentiment for at least a pro forma trial prevailed, and a tentative plan for a two-week trial was agreed upon.

Once House Speaker Nancy Pelosi publicly announced that articles of impeachment would be drafted and acted upon in the House Judiciary Committee, Trump suddenly began talking about an extended trial in which he, his attorneys, and his Senate allies will not simply defend him but will seek to place Joe and Hunter Biden and perhaps other leading Democrats on trial as well (echoing House Republican demands that Adam Schiff and other Trump tormenters be hauled in to testify about their persecution of the president). A true show trial of Democrats may well be a bridge too far for Senate Republicans. But to the extent that Trump can claim dragging the Bidens into the dock is necessary to document the corruption he claims he was seeking to root out in pressuring Ukraine’s president to investigate them, a compliant Senate Republican majority and a chief justice trying not to become too central to the proceedings might allow it to happen.

What Governs the Conduct of the Senate Trial?

Regardless of how it begins or ends, the trial itself is governed by standing Senate rules, last modified in 1986. They are largely based on precedents set in the Andrew Johnson impeachment trial. The basic idea is that articles of impeachment are presented to the Senate by House impeachment managers, and are then disputed by counsel for the president, with senators observing but not becoming directly involved (other than by written questions submitted to one or both of the parties).

Witnesses are called and cross-examined according to protocols and timelines set out in the standing rules–which provide for rulings on witnesses and admissible evidence by the Chief Justice, with the Senate able to overrule him by a majority vote–perhaps supplemented by a set of more detailed ad hoc rules adopted by the Senate just before the trial begins on a majority vote (a two-thirds vote is required to actually change or override the standing rules). During the Clinton impeachment proceedings, ad hoc rules were (somewhat miraculously) adopted by unanimous consent, in part because the outcome of the trial was in zero doubt. Even though the outcome of a Trump trial may also be preordained (e.g., acquittal on a more or less party-line vote), any bipartisan procedural agreements are unlikely. Yet Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer has repeatedly demanded that McConnell come to the table to negotiate such a deal, in part to force Republicans to issue subpoenas (under the authority of the chief justice, the trial’s presiding officer) to four witnesses the White House blocked from appearing during the House proceedings, notably acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney and former national security advisor John Bolton (who has indicated he would obey such a subpoena).

From the very day the House passed its articles of impeachment, Speaker Nancy Pelosi has delayed sending over the articles of impeachment, supporting Schumer’s demand for an agreement to hear more witnesses. She and McConnell have subsequently engaged in a standoff over this issue; at one point McConnell expressed support for legislation (which as an amendment to the standing Senate rules on impeachment would take 67 votes) to cancel any impeachment trial if the House failed to present its articles within 25 days of impeachment.

Most recently, on January 10, Pelosi notified House Democrats that she would ask for a resolution the next week appointing impeachment managers (the House members who will present the case for removing Trump in a Senate trial) and authorizing the presentation of articles to the Senate. Unless there is some catch (e.g., a contingency clause in the resolution further delaying the presentation of articles until McConnell complies with some Democratic demand), the trial could start on the week of January 20.

The question of witnesses and additional evidence could remain up in the air for some time. McConnell has indicated that he’ll pass a set of ad hoc trial rules without Democratic support, and begin the trial while delaying decisions on witnesses until later; he claims to have 51 Republican votes for this maneuver. But Senate Democrats are very likely to challenge this decision at every point, and put pressure on Roberts to allow relevant evidence and witnesses just like a trial judge would do.

Who Makes the Principal Arguments In an Impeachment Trial?

The Senate’s standing rules provide that the case for removing the president is made by the House impeachment managers. They will make their arguments first, subject to questioning (in writing) by senators. The president’s response follows, made by his appointed counsel. It is generally assumed his White House counsel will lead the defense, but there are really no limits on how the president chooses to be represented.

There’s been talk recently of Trump including key House Republicans (e.g., those involved in fighting impeachment like the Judiciary Committee’s ranking Republican Doug Collins or the Judiciary/Intelligence Committee members Mark Meadows and John Ratcliffe) on the president’s trial team, but McConnell has frowned upon the idea as threatening the trial’s decorum and making it simply a continuation of the House battle.

Are Senators Under a Gag Order on Impeachment?

One aspect of the trial procedure as spelled out by the standing rules was alluded to by McConnell in his discussions with his Republican colleagues earlier this year:

McConnell … warned that senators won’t be allowed to speak because they are jurors. McConnell said such silence “would be good therapy for a number of them.”

More accurately, senators are like jurors — and judges, too — in that they observe the back-and-forth between House managers and their lawyers and the president and his lawyers and don’t have an opportunity to speak until they go into a closed session to deliberate. The standing rules also provide that when it comes time to vote, each senator stands by her or his desk and simply announces “guilty” or “not guilty” on each article of impeachment. And at the beginning of the trial, they do take an oath to act impartially, a requirement that gained attention when McConnell spoke of ‘total coordination” with the White House and senators from both parties expressed certainty about the president’s guilt or innocence.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the Senate’s standing rules are subject to amendment, which would normally require a supermajority. But as Bob Bauer observed at Lawfare blog, there are ways around that problem for a devious operator like McConnell:

Senate leadership can seek to have the rules “reinterpreted” at any time by the device of seeking a ruling of the chair on the question, and avoiding a formal revision of the rule that would require supermajority approval. The question presented in some form would be whether, under the relevant rules, the Senate is required to hold an impeachment “trial” fully consistent with current rules — or even any trial at all. A chair’s ruling in the affirmative would be subject to being overturned by a majority, not two-thirds, vote.

In any event, the “silence” expected of senators is not imposed until the articles of impeachment are passed by the House and presented to the Senate — i.e., until the trial begins. So when you hear senators say they won’t comment on impeachment charges or the possibility of “impeachable offenses” having been committed to avoid prejudging a “case” they may try as “jurors,” that’s a purely voluntary and informal assertion. From the perspective of the Constitution and the standing Senate rules, they can run their mouths all they want before and after the trial. But some may choose to hide behind the “prospective juror” fiction to keep their own counsel, as became clear when Senator Lindsey Graham proposed sending a letter to Pelosi informing her that the Senate had no intention of removing Trump from office over the Ukraine scandal, as the Hill reported:

Several, including Sens. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Susan Collins (R-Maine), have declined to weigh in on the impeachment proceedings and admonished their colleagues who have already made a decision.

Collins, one of two GOP senators up for reelection in a state won by Hillary Clinton, told reporters in Maine that it was “entirely inappropriate” for senators to be taking a position.

Romney declined to comment on Wednesday on Graham’s letter, but he said last week that he was going to keep “an open mind” on impeachment.

“It’s a purposeful effort on my part to stay unbiased, and to see the evidence as it’s brought forward,” he said.

Other Senate Republicans are reportedly raining on Graham’s parade, not because they believe they are required to remain silent but because they don’t want to display any Republican disunity or place vulnerable senators on record this early in the process.

What’s unclear is whether the tradition of senators not speaking during the trial imposes some sort of restriction on comments during evenings, early mornings, Sundays or other times the trial is not in session. This question is of particular importance to the Democratic senators (currently six of them) who are running for president. The trial will undoubtedly interfere with their campaign activities, but it’s unclear whether some ad hoc Senate rule or ruling from the presiding officer (the chief justice) will constrain their free speech rights until the final vote.

When Will the Trial Begin and End?

Obviously, the Senate cannot start the trial until the House sends over the articles of impeachment; under the standing Senate rules, the obligation to begin a trial arises very quickly once the articles are formally presented by the House impeachment managers (in other words, an email or other notification will not suffice). And if McConnell does agree to witnesses, that will extend the duration of the trial. Here are the precedents, as I noted recently:

The Johnson impeachment trial in 1868 lasted from March 5 until May 16, when the Senate’s first crucial “test vote” on a catch-all article of impeachment failed by one vote. Ten days later the Senate voted predictably to acquit on two other articles, and subsequently voted for general acquittal and adjournment.

Clinton’s impeachment trial was more hurried: It began on January 7, 1999, when presiding officer Chief Justice William Rehnquist was sworn in, and ended on February 12, with Clinton’s easy acquittal on both articles (45 senators, all Republicans, voted for his guilt on the perjury article, with ten Republicans defecting; and 50 senators vote for the obstruction article, with five Republicans defecting).

The timing of the trial has special significance because it is likely to overlap with the Democratic presidential nominating contest, in which, at present, five sitting senators are participating. It will certainly take a bite out of the time they have available for the campaign trail.

The final votes in the Senate will be dramatic but largely anticlimactic, like those in the Clinton trial, more than likely. It takes just one “guilty” verdict to remove a president from office, but that requires 67 votes – or in this case, the defection of 20 Republican senators. Even if a handful of Republican senators (e.g., Mitt Romney or a few colleagues like Susan Collins or Cory Gardner who face tough 2020 challenges) declare their independence, Trump will be free to claim exoneration and seek vindication next November as the newly triumphant chieftain of his defiant MAGA constituency.

So as we expected all along, the real court in this trial will be the court of public opinion. Every maneuver either side makes in this trial–particularly persistent Democratic efforts to bring in more evidence of the president’s impeachable conduct–should be understood from that perspective.

This post has been updated to reflect new developments.