A few weeks ago, the Washington Post published a trove of confidential documents detailing “explicit and sustained efforts by the U.S. government to deliberately mislead the public” about the prospects for victory in Afghanistan. These papers revealed that America’s military commanders distorted “statistics to make it appear the United States was winning the war when that was not the case,” while its civilian leadership buried intelligence testifying to the Taliban’s resurgent strength. The aim of this systematic mendacity was to insulate our foreign-policy elites’ plans for “winning” the conflict from the threat of an informed public debate. And yet, even as our leaders sacrificed democratic accountability to the higher cause of military victory, they had no clear idea of how to define the latter concept, let alone achieve it. Now, 18 years, $1 trillion, and over 2,300 American deaths later, the U.S. military is slowly but surely bequeathing Afghanistan to the Islamist forces that U.S. troops were trying to topple in the first place.

One week after the Post alerted the public to this historic scandal, Congress rewarded the bureaucracy responsible for it with a $22 billion budget increase. Before Donald Trump took office, the U.S. was spending more on its military each year than China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan’s military spending, combined. With the passage of the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the Pentagon’s budget is now $130 billion larger than it was in 2016. Meanwhile, nearly 2 million Americans are still living in places that do not have running water.

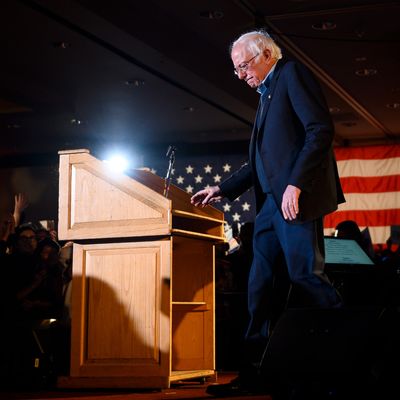

Eighty-six senators voted for that NDAA. Bernie Sanders was not one of them. Despite the Post’s revelations — and the Taliban’s impending triumph — almost no one in Congress has been willing to describe the war in Afghanistan as a mistake. The socialist senator is an exception.

In recent weeks, as Sanders has secured his grip on second place in the Democratic primary, the senator’s heretical views on foreign policy have attracted media scrutiny. The tenor of this coverage tends to be facially neutral, but tacitly skeptical, if not outright alarmed. A Washington Post story titled “How Bernie Sanders would upend America’s global role” is a representative example. Sean Sullivan’s account of how a Sanders presidency could rattle “the world order” is somewhat fair-minded, dutifully acknowledging that history has proven the senator’s instincts on Iraq prescient. But the piece’s overwhelming emphasis is on the radicalism of Sanders’s views — a radicalism that it simultaneously exaggerates and declines to contextualize. The piece repeatedly informs its readers of the marginal position that Sanders has taken on a given issue, without offering any insight into whether that stance is well-reasoned or substantiated. The fact that his opinions are marginal is treated as more relevant than whether they are correct.

This prioritization is made clear in the piece’s opening paragraphs:

When Bolivia’s leftist president was pressured to resign by his country’s military after an audit found signs of a tainted election two months ago, many American leaders showed little interest in condemning the ouster. Some said it was a potentially positive step for democracy — a sign, as President Trump put it, that “the will of the people will always prevail.”

A sharply different response came from Sen. Bernie Sanders, who immediately condemned “what appears to be a coup.” The ousted leader, Evo Morales, who had challenged term limits to remain in power, later thanked the senator from Vermont and Democratic presidential candidate, referring to him affectionately as “brother.”

Readers are never provided with Sanders’s argument for seeing Morales’s ouster as an apparent coup, nor with information as to how ensuing events in Bolivia have validated or contradicted the senator’s assessment. We are only told that Morales presided over a tainted election and challenged term limits to remain in power. Among the things we are not told: (1) No one disputes that Morales won the most votes of any candidate in that “tainted” election, only whether his true margin was large enough to avoid a runoff, (2) in light of the audit’s concerns on the latter point, Morales agreed to convene new elections, (3) some well-reputed election analysts have disputed the audit’s premises, and (4) Morales’s ouster brought a far-right, anti-indigenous faction to power that had received no democratic mandate whatsoever, and nevertheless proceeded to overstep its bounds as a caretaker government. As the Guardian reported in December:

Interim president Jeanine Áñez vowed to unify the country when she took power — but packed the cabinet with members of the conservative elites and boasted that “God has allowed the Bible back into the palace” of a secular country. She exempted the military from criminal prosecution when maintaining public order; at least 17 indigenous protesters died after security forces opened fire. Police cut the indigenous Wiphala flag from their uniforms and anti-Morales demonstrators set fire to it. The interior minister has vowed to jail Mr Morales, in exile in Mexico, for 30 years for terrorism and sedition.

These are not the only relevant facts, of course. Morales did ignore a democratic mandate in favor of term limits, and had attracted real grassroots opposition, not only from the upper strata of Bolivian society but also pockets of its left. It is possible that Sanders’s initial reaction to Morales’s ouster was informed more by kneejerk sympathy for a fellow socialist than a careful appraisal of the situation. But from the few details the Post provides, a lay reader would scarcely gather that subsequent events have done far more to vindicate Sanders’s description of Morales’s fall than Donald Trump’s. The important thing to know is that the president’s view was more in keeping with mainstream sentiment. The validity of that mainstream sentiment demands no scrutiny.

This indifference to the merits of Sanders’s heresies is maintained in subsequent paragraphs:

Beyond his objection to Morales’s removal, Sanders has pointedly declined to label Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro a dictator. He called Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu a “racist,” and he has campaigned with Reps. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) and Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), vocal supporters of a controversial Israel boycott movement. He said China has done more to address extreme poverty “than any country in the history of civilization.”

There is little question that Maduro is a corrupt and illiberal leader. But Merriam-Webster defines dictator as “one holding complete autocratic control.” The fact that an opposition movement secured control of Venezuela’s National Assembly and proceeded to challenge the legitimacy of Maduro’s claim to the presidency would seem sufficient to establish that — at least for now — his autocratic control of Venezuelan politics is less than complete. Benjamin Netanyahu, meanwhile, warned supporters on Election Day in 2015 that “Arabs” were “being bused to the polling stations in droves” — suggesting that Arab Israelis’ participation in the democratic process was on its face a cause for alarm. He later has made alliance with a Jewish supremacist party so virulently anti-Arab, AIPC has denounced its views as “reprehensible.” And, of course, Netanyahu presides over a military occupation that denies Palestinian residents of the West Bank basic political rights by dint of their ethnic identity. Finally, Sanders’s assessment of China’s progress on poverty isn’t actually heretical. It’s the conventional wisdom of Davos, a cornerstone of every apology for neoliberal globalization.

Sullivan ostensibly includes Sanders’s echo of this conventional wisdom in his litany because it comports with a Cold War–era conception of what it means to buck bipartisan foreign-policy consensus from the left — namely, to be “soft” on authoritarian socialism. But the notion that the main disagreement between leftists and Cold War liberals on foreign policy concerned the permissibility of allying with autocrats was never credible. And in the present context — in which America’s most powerful corporations routinely abet Chinese propaganda, and billionaire centrists like Mike Bloomberg defend the legitimacy of Xi Jinping’s rule — the premise is facially absurd. Sympathy for Communist China is not an aberrant trait of 21st-century progressives in general, or of Bernie Sanders, in particular. In fact, the Vermont senator has accused Xi’s government of “cultural genocide,” and cast it as principal member of an “international authoritarian axis” that America must use its soft power to combat.

The discrepancy between Sanders’s actual position on China and the one the Post implicitly attributes to him is reflective of the piece’s broader hyperbole. From Sullivan’s article, one would never guess that Sanders is not actually a reflexive opponent of U.S. military intervention, and supported Bill Clinton’s bombing of Kosovo, or that he has made qualified defenses of using drone strikes to preemptively murder alleged terrorists overseas. Sanders’s dissent from his nation’s imperial prerogatives is not absolute.

I suspect that the impulse to exaggerate Sanders’s foreign-policy radicalism, and the impulse to elide the factual basis for his blasphemies, are related. If the bipartisan consensus on foreign policy were easier to defend on the merits, there would be less need to paint its progressive apostates as ideologically blinkered suckers for neo-Soviet regimes. It isn’t the extremity of Sanders’s worldview that makes it threatening to the “world order” (as the Post conceives of that phrase), but its reasonableness.

Congress’s bipartisan foreign policy consensus asserts that the United States has a vital interest in preserving Saudi hegemony in the Middle East (even though Riyadh’s totalitarian Islamist regime is more oppressive than Iran’s, sponsors jihadism, and is no longer needed as a supplier of oil to the U.S. economy); that Israel cannot defend itself unless U.S. taxpayers subsidize its army (even though it is a wealthy nation with one of the world’s most powerful militaries); that terrorism poses such a dire threat to Americans’ physical well-being, the U.S. must bestride the globe preemptively executing every Islamist militia we deem suspicious (even though fewer than 300 Americans have been killed by terrorists on U.S. soil since 9/11, and majority of those deaths came as a result of domestic extremists); and, above all, that the Pentagon’s budget should always be higher (no matter how many trillions of dollars the Department squanders while misleading Americans into endless wars that exacerbate the very problems they were launched to solve).

The fundamental cause of all this rabid irrationality is simple: America’s foreign-policy consensus is forged by domestic political pressures, not the dictates of reason. Saudi Arabia’s oil reserves may no longer be indispensable to the U.S. economy, but its patronage remains indispensable to many a D.C. foreign-policy professional. Israel may no longer be a fledgling nation-state in need of subsidization, but it still commands the reflexive sympathy of a significant segment of the U.S. electorate. Terrorism may not actually be a top-tier threat to Americans’ public safety, but terrorist attacks generate more media coverage than fatal car accidents or deaths from air pollution, and thus, are a greater political liability than other sources of mass death. And the Pentagon may have spent much of the past two decades destabilizing the Middle East and green-lighting spectacularly exorbitant and ill-conceived weapons systems, but the military remains one of America’s only trusted institutions, and its contracts supply a broad cross section of capital with easy profits, and a broad cross section of American workers with steady jobs.

Bernie Sanders is not immune to the gravitational force of these political realities. But he is more resistant to Congress’s collective madness than most of his peers. The senator has consistently opposed increasing the Pentagon’s gargantuan budget, called for rethinking the U.S. alliance with Saudi Arabia, and threatened to withhold U.S. military aid to Israel if it continues to expand settlements in the West Bank. To be sure, the man is no foreign-policy wonk. And his stated views on trade can be reductive and nationalistic. But on the whole, his outlook is both more evidence-based and more moderate — with its cautious approach to foreign intervention and allergy to unilateral assertions of American power — than the consensus he threatens to “upend.”