Every presidential election cycle, there are vanity candidates: pols or wealthy business people who have the determination, the resources, the ego to persist in the difficult task of running for president despite abundant signs that it’s not working. Many observers accuse 2020 candidates Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer of running that kind of campaign, wasting tens and even hundreds of millions of dollars better spent on promoting the Democratic Party or down-ballot candidates.

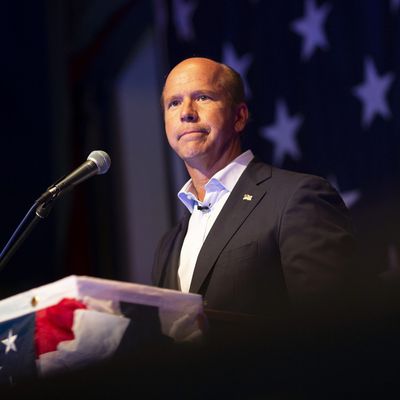

But before either of these men got into the fray, there was another wealthy candidate who launched a presidential campaign long before anyone else, made a brief but not necessarily positive mark on the contest, and then hung in through thick and mostly through thin before abruptly leaving the race just three days before the Iowa caucuses: former Maryland congressman John Delaney.

A three-term congressman from a gerrymandered district running from the D.C. suburbs into western Maryland, and before that a successful (and largely self-made) banker, Delaney emulated another Marylander, 2016 candidate Martin O’Malley, in following the “book” by getting into the race early and focusing obsessively on Iowa. Indeed, nobody was going to beat Delaney to the starting post: He announced his candidacy on July 28, 2017. Unlike O’Malley, Delaney was rich enough to self-fund (loaning over $20 million to his campaign), and by declining to run for reelection in 2018, he was able to run full-time. By the end of 2018, he had completed the so-called “full Grassley,” with appearances in all 99 Iowa counties, a feat many presidential candidates never accomplish. By the autumn of 2019, he had spent a total of 80 days in the state, holding 229 events. From the get-go, he identified himself as a member of the moderate, “pragmatic” wing of his party. But his early start didn’t do much for him in terms of early popularity.

The first edition of the gold-standard Iowa Poll from Ann Selzer (sponsored by the Des Moines Register, CNN, and Mediacom) in December of 2018 measured Delaney’s total first- and second-place support at one percent, and his favorable-unfavorable ratio at a meh 25-11. After all that campaigning and even some TV ads, the most recent Iowa Poll earlier this month gave him a nice round zero in first- and second-choice support, and a terrible favorability ratio of 15/40.

Delaney qualified for the first and second candidate debates; after the first one in June of 2019 his campaign staff reportedly urged him to drop out. But it was in the second debate in July that Delaney made his first and only impression in the national contest, cast by combat-loving CNN moderators as the Fighting Moderate warning Democrats of the nefarious radicalism of Sanders and Warren, as my colleague Matt Stieb reported at the time:

During the first night of the second round of Democratic debates, the former Maryland representative appeared with great regularity, to the point that observers began to dabble in conspiracy theories …

[I]n some of his more notable moments, it seemed he was brought in mainly to set up a question for a front-runner, as was the case when Jake Tapper shifted from the former Maryland representative to Bernie Sanders on Medicare for All or the switch from Delaney to Warren on the issue of electability and big ideas.

Thanks to his bad and even worsening poll numbers, Delaney never made another debate stage, though he continued his attacks on the leftward drift of the more successful candidates and continued to haunt the highways and byways of Iowa.

So why did he finally quit, just three days before the event toward which he had labored for so very long? Here’s the official explanation as reported by NBC News:

In a statement, his campaign said that his decision “is informed by internal analyses indicating John’s support is not sufficient to meet the 15% viability in a material number of caucus precincts, but sufficient enough to cause other moderate candidates to not to make the viability threshold, especially in rural areas where John has campaigned harder than anyone.”

Delaney, a moderate Democrat, said on CNN Friday morning that he did not want to take away votes from other moderate candidates, such as former Vice President Joe Biden, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg.

With all due respect, it’s unlikely that Joe Biden is going to need John Delaney’s supporters, such as they are, to reach 15 percent anywhere. And while it’s possible that the odd Delaney fan could happen to push Buttigieg or Klobuchar over the viability threshold here or there, there are probably more important variables for these campaigns, like the availability of parking or the quality of baked goods brought by volunteers.

All in all the Delaney candidacy is a cautionary tale in what can happen when a pol goes by the book in Iowa and just won’t stop when it clearly isn’t working. But after the Caucuses come and go, Sanders and Warren may feel nostalgic for the presence of Delaney as a foil.