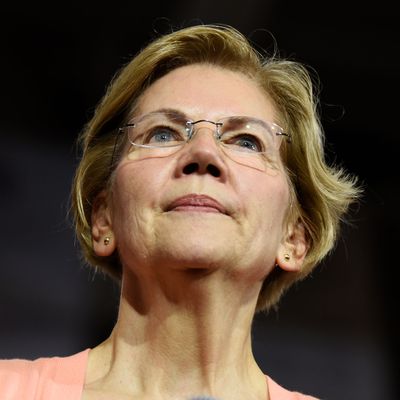

Perhaps the most commonly heard observation at year’s end about the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination contest was how little things had ultimately changed during 2019, which began and ended with the very familiar late-septuagenarian odd couple of Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders riding high over the field. But underlying this reality is another one: During the autumn of 2019 Elizabeth Warren, who looked to be putting Sanders in her rearview window and challenging Biden, began to lose steam and now may not be in any sort of top tier with the two old men.

According to the national polling averages at RealClearPolitics, Warren’s share of the vote during the last three months dropped from 26.8 percent, a virtual tie with Biden for the lead, to 14.2 percent, in third place, six points behind Sanders and with less than half of Biden’s support. There’s no obvious reason why her support has fallen so far so fast; she hasn’t had a bad debate performance or committed some terrible gaffe. Yes, she still trails Sanders on the fundraising front, as does everyone else, but her fourth quarter 2019 haul of over $21 million placed her in the same neighborhood with Biden and fundraising phenom Pete “Wine Cave” Buttigieg. She has by all accounts competently invested her resources in building a strong, highly professional organization in the early states, along with infrastructure in the Super Tuesday states and beyond.

She also, in theory at least, may have a strategic advantage as the candidate best able to truly unite the progressive and “moderate” wings of her party. One rival for that role, Kamala Harris, is no longer in the race, and another, Pete Buttigieg, seems to be aggressively aligning himself with party centrists.

But on the other hand, that might be Warren’s problem: Activists in her party may not be presently in a mood to compromise, as evidenced by the fact that she is now getting ground up by criticisms from left and center, much of it, interestingly enough, flowing from her positioning on Medicare for All. The New York Times’ Asted Herndon, in an assessment of her struggles, noted how she’s been able to please no one:

It will be an electoral tightrope walk of the highest order, as evidenced by the way the debate about Ms. Warren’s health care plan consumed the final months of 2019. It started with the race’s moderates, who pressured Ms. Warren into providing additional details about how she planned to pay for and transition to a “Medicare for all” system. When those details diverged from the outline in Mr. Sanders’s bill, some members of the party’s left flank accused her of political betrayal.

It’s unclear to me how anyone other than Warren can simultaneously appeal to Democrats who don’t like Medicare for All or consider it a pipe dream, and those who somehow believe it can be enacted immediately in a patently hostile Congress. But at this point, and without too much overt firing at each other, many Democrats prefer to remain in their separate tents led by the old guys.

Aside from ideological sniping at Warren from both directions, another problem has seeped down from elite political analysis to actual voters, according to Herndon:

Ms. Warren’s conundrum is tied to the all-important notion of “electability,” the vague and sometimes discriminatory concept that has become paramount to Democratic voters who are motivated by defeating Mr. Trump.

When Ms. Warren’s campaign was riding high in the summer and early fall, the energy around her ideas was an implicit message to both liberals and moderates: She was the one who could win.

But now as her bandwagon has slowed, fears about her electability have revived, fed by the very influential polling of Herndon’s Times colleague Nate Cohn, as Isaac Chotiner explained in November:

On Monday, the New York Times and Siena College released a poll of how Donald Trump is faring against three leading Democratic Presidential opponents — Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren — in six critical swing states, all of which Trump won in 2016. The results contain bad news for Warren, despite her strong showing with Democratic-primary voters in Iowa; against President Trump, she performs worse than Biden or Sanders, with Trump leading or tied in five of six swing states. Biden leads or is tied with Trump in five of the six states, while the Times/Siena poll shows Trump and Sanders running essentially even. The Times’ Nate Cohn, who oversaw the poll, wrote of Warren, “not only does she underperform her rivals, but the poll also suggests that the race could be close enough for the difference to be decisive.”

This finding was closely linked to Cohn’s strong belief that swing voters hostile to social liberalism living in Rust Belt battleground states are the most likely keys to 2020. And that in turn triggered the almost superstitiously powerful belief of some Democratic beliefs that the real reason Hillary Clinton lost to Trump is that Americans “aren’t ready” for a woman — particularly an older woman — to serve as president.

As it happens, I have criticized this mindset as representing a misogynistic triumph for our misogynist president:

Add in the evidence that Democratic voters express more enthusiasm for the presidential candidacy of a woman and/or person of color than of another white guy — stronger than the evidence Clinton lost because she is a woman — and it becomes clear the fears about actually nominating a woman are almost entirely a matter of assuming that Trump’s misogyny is shared by the voters who will decide the 2020 elections. And beyond that, the fears reflect the atavistic gut conviction that the purple-state backlash against a women will exceed the frontlash from those happy, finally, to break that last political glass ceiling. Trump has so thoroughly demoralized Democrats that they are exhibiting sexism in their own political judgments in the guise of “electability.”

Understanding fears about Warren’s electability as misguided do not, however, dispel them at a time when Democrats are rightly terrified about the consequences of a second Trump term. So even if Warren looks like a heaven-sent unity candidate for a potentially divided party, and one who commands unparalleled respect as a policy thinker, if Democrats fear she’s a loser in a general election, she’ll lose in the primaries.

The silver lining for Warren is that nothing dispels such fears quite like a tangible sign of electoral strength, and she will have the opportunity to pull one off in Iowa, where her strong organization and retail skills remain big assets. Thanks to the recent polling dearth there, it’s unclear whether her national slide has proportionately damaged her standing in Iowa; the one recent poll from CBS/YouGov shows her trailing her three main rivals (Biden, Buttigieg, and Sanders) by seven points. Next week’s debate in Des Moines will provide a good opportunity for her to remind Iowans of her virtues. And among them they may wind up focusing on her potential as a party unifier in the white-hot horse-trading atmosphere of the Caucuses.