While the cause of Kobe Bryant’s helicopter crash has not yet been determined, the weather and terrain conditions were similar to those that have killed many helicopter pilots over the years, with fog and clouds masking rugged, rising terrain. The reconstruction of his flight that follows is based on information from transponder data, air traffic control audio recordings, and my own experience as a pilot who was trained in the exact area where the incident took place.

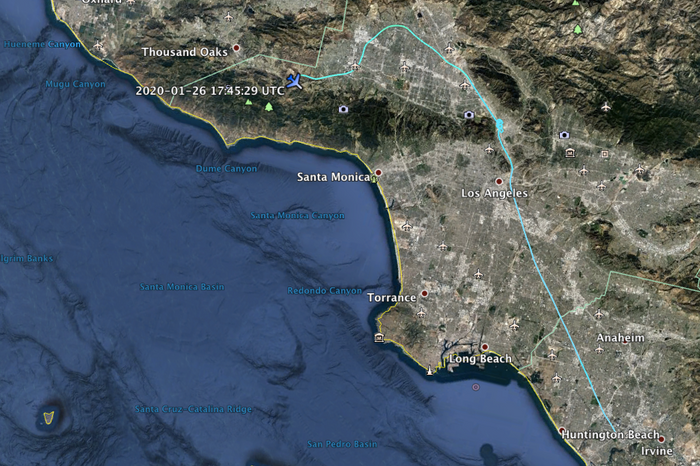

Bryant’s helicopter, a Sikorsky S-76B built in 1991, took off shortly after 9 a.m. from John Wayne Airport in Orange County, which is located near the coast approximately 35 miles south of downtown L.A. According to the New York Post, Bryant and the eight other passengers were heading to a basketball game at his Mamba Sports Academy in Thousand Oaks, approximately 70 miles to the northwest. Over the course of the next 40 minutes, the helicopter would trace a circuitous route around the Los Angeles basin as it negotiated mountains and busy airspace in three main phases: first, cutting across the broad coastal plain of central Los Angeles, then winding around the basin of the San Fernando Valley to its north, before a final ill-fated attempt to cross the rising terrain that led west to Thousand Oaks.

At takeoff a few minutes after 9 a.m., the weather was marginal, with a solid overcast at 1,300 feet and visibility of about five miles in a thin haze. The pilot was flying according to “Visual Flight Rules,” or VFR, meaning that he was relying on his ability to see the terrain below him, and hence had to stay below the clouds. As an alternative, he could have contacted air traffic controllers and switched to “Instrument Flight Rules,” or IFR, that would have allowed him to climb up through the clouds. Controllers would have given him a series of waypoints to follow that would keep him well clear of terrain, dangerous weather, and other aircraft. Flying IFR, however, is time-consuming and constrains pilots to following the directions of controllers. “Southern California airspace is extremely busy, and they might tell you to wait an hour,” assistant professor of aviation at the City University of New York Paul Cline told me. “You’re just one of many waiting in line, and it doesn’t matter if you’re Kobe Bryant.”

So the helicopter continued under visual flight rules. According to data transmitted continuously by the plane’s transponder, it climbed to an altitude of 800 feet as it headed to the northwest near its top speed of 178 mph. For the next 12 minutes, it sped over the inland sprawl of Orange County, past former citrus groves that had long ago been repurposed as warehouses and strip malls. It left the beach enclave of Huntington Beach to the left, and Disneyland to the right, as it worked its way north and west, drawing ever closer to the east-west range of hills, the Santa Monica Mountains, which define the northern end of Los Angeles proper and shelter the city’s most storied redoubts: Beverly Hills, the Hollywood Hills, Malibu.

As he skirted downtown L.A. — and the stadium where Bryant had spent the entirety of his 20-year career — the pilot picked up Highway 5, one of the state’s main arteries, and followed it north to Glendale, a sort of gateway between L.A. proper and the San Fernando Valley to the north. To the left, the peaks of the Santa Monica Mountains disappeared into the clouds; to the right rose the Verdugo Hills. Low-level aviation in the greater L.A. area is constrained by the mountains and the passes that cut through them. Fortunately for pilots navigating by sight, the major highways also make use of these passes, so in a pinch a disoriented pilot can find his way through by following the traffic. There’s an old joke that “IFR” stands for “I Follow Roads.”

But before Bryant’s helicopter could enter the San Fernando Valley, it had to wait. Directly ahead lay Burbank Airport, surrounded by an invisible cylinder of airspace 10 nautical miles across that cannot be entered without permission from air traffic control. Here, near Griffith Park, the helicopter slowed and started a series of turns to the left. After 11 minutes, permission to proceed came through, and the helicopter accelerated as it resumed its northward track over the 5.

Five minutes later, the helicopter reached the edge of Burbank’s airspace. As the 5 turned north on its way to the Bay Area, the helicopter kept straight, then followed a long curve to the left that carried it around the northern half of the San Fernando Valley to skirt the busy airspace around Van Nuys Airport.

At 9:42 a.m., the helicopter intercepted the Ventura Freeway near the southwestern corner of the San Fernando Valley. To the left, the rectilinear sprawl gave way to the wooded slopes of the Santa Monica Mountains and Malibu beyond. Straight ahead, the freeway climbed and zigzagged as it negotiated the higher terrain that led to Thousand Oaks. The journey was almost at an end: the Mamba Sports Academy lay just 17 miles to the west.

For the first time, though, the helicopter was no longer flying over the flat expanse of dense urban Los Angeles. Here, at the suburban fringes, the terrain was hilly and climbing. To make matters worse, the canyon that stretched to the south has a tendency to funnel in the maritime fog. That morning, said Calabasas resident Sharon Stepanosky — who lives less than a mile from the crash site and who happens, coincidentally, to be my cousin — a thick fog had lain over the area, with visibility no more than a few hundred feet. “It was completely overcast and visibility was not good,” she said. By 9:45 a.m., rising temperatures had driven away the fog from the majority of the town, but thick low clouds still wrapped around the slopes just a few hundred feet higher.

As the helicopter approached Calabasas, it was less than 500 feet above the ground. Perhaps wanting to put a safety margin between himself and the increasingly hilly terrain, the pilot began a brisk climb, ascending nearly 1,000 feet in 36 seconds. This put it very close to the bottom of the cloud layer reported at that time at nearby Van Nuys Airport.

We may never know for sure if the helicopter had indeed entered the clouds. But if it did, then it had crossed a kind of invisible line. It was now engaged in what air-crash investigators call “continued VFR flight into instrument meteorological conditions.” Basically, a pilot dependent on seeing the ground to stay oriented can no longer see the ground. Amid a sudden whiteout, disorientation can come surprisingly quickly. “When you get in the soup, your senses don’t work,” Cline, the aviation professor, said. “For me, I always feel like I’m falling to the right. Other people might feel like they’re falling to the left, or climbing.”

A trained pilot can stay right-side up by paying attention to the instruments on his panel. But at low altitude over Calabasas, Bryant’s pilot also had another problem. He knew that the ground ahead was rising, and he couldn’t see it. To avoid hitting it, he could keep climbing, and hope that he’d gain altitude faster than the ground underneath him. Or he could slow to a stop and descend vertically until he popped out of the bottom of the cloud.

Based on the subsequent track of the aircraft, however, it seems that the pilot decided to take a third option. According to data transmitted by its transponder, at 15 seconds past 9:45 a.m. the pilot banked to the left, then dove. Why? We can never get into his head to know for sure. But based on my own experience flying light aircraft, the sudden intensification of danger creates of sense of mental overload in which it’s nearly impossible to rationally weigh one’s various options. Instead, one takes the most immediate and obvious choice. In this case, that meant trying to get back into clear air by diving back under the cloud layer while pulling a hard 180 to retreat from the dangerous terrain.

Eighteen seconds after beginning the turn, the helicopter had lost 800 feet and returned to an easterly heading. But what the pilot had failed to reckon with is that the ground rose not only straight ahead, but on the sides as well. The S-76B had impacted a hillside above the Los Virgenes Municipal Water District facility at a speed of 170 mph.

To be clear, this scenario is just one possibility. “I can’t stress enough, we do not know what happened,” said Cline. It’s possible, he acknowledges, that the plane suddenly developed a mechanical problem that forced it down. Still, he can’t help but be haunted by the idea that if Bryant’s pilot had decided to fly IFR, he and his passengers would still be alive.

“A ton of rules come into play, and people don’t always want to fly that way. It takes away their ability to do whatever they want to do,” Cline said. “The trade-off is you get to live.”