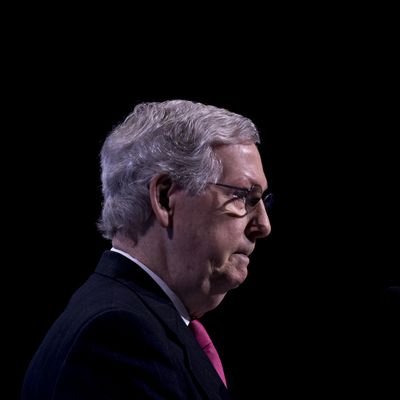

The smartest thing the wily Mitch McConnell did in planning the impeachment trial of Donald Trump was to line up 51 Republican votes for his “organizing resolution” — the detailed trial protocols addressing matters not prescribed by the Constitution or the standing Senate rules — before anyone had a chance to read it. The big issue when the majority leader was whipping his conference was whether the Senate could begin the trial and hear opening arguments without consideration of witnesses and new evidence, and that remains the biggest controversy.

Initially, it appeared McConnell had also nestled into the resolution some other stink bombs, including 12-hour sessions ending as late as 1 a.m. to hear the opening arguments, a ban on presentation of evidence collected by the House without a Senate vote to allow it, and a requirement that any witnesses eventually called first have to be deposed by both sides in the trial. But when the resolution was actually read in the Senate, we learned McConnell had relented on a few of those points. First, he had substituted “three days” for “two days” in the timetable for each side’s opening arguments (in the Clinton trial the same length of presentations were held over four days). That means eight-hour as opposed to 12-hour presentations; depending on how many breaks the Senate takes, sessions could end in the late evening rather than the wee hours. Perhaps McConnell was displeased with the new moniker “Midnight Mitch,” or maybe Republican senators objected to the breakneck schedule. The resolution also dropped the requirement that the House record could not be entered into evidence without a Senate vote, which was mostly there to annoy Democrats.

The deposition requirement, which remained in the resolution, is one of several elements of the Republicans’ fallback strategy if witnesses are eventually called. McConnell and the White House obviously hope that 51 senators agree not to hear any witnesses (it’s theoretically possible, though unlikely, that Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts would rule to allow new evidence or even witnesses in his capacity as presiding officer of the trial). If witnesses are allowed, then an opportunity to depose, say, John Bolton, would provide Trump’s lawyers a convenient moment to assert executive privilege to block the testimony (by appealing to the chief justice to make a ruling in their favor, or even by going to federal court and seeking an injunction). They could also demand, in Bolton’s case, that the witness be heard by the Senate in a closed session due to national-security concerns.

The final element of the GOP’s button-it-all-up strategy is to threaten that if Bolton or other witnesses to Trump’s impeachable acts are called, then the president’s team should be allowed to call Hunter Biden or Joe Biden or Alexandra Chalupa or some other alleged figure in the Ukrainian corruption and election-tampering plot Republicans are fatuously but consistently alleging. If the requisite four Republican senators do vote to hear Bolton, they might be hard-pressed to deny Trump his own witnesses, and things could get weird in a hurry. That possibility could convince Senate Democrats to pull their punches a bit.

If everything goes as McConnell wishes, however, he’ll get his 51 votes on the organizing resolution (despite Chuck Schumer’s efforts to amend, delete, or modify all the provisions addressed above). Then, after each side’s opening arguments are heard, McConnell will get at least 50 votes to block motions to hear Bolton or other witnesses, and the trial can be wrapped up in time for Trump’s State of the Union Address on February 4, when he can either bellow triumphantly or play the conciliatory victim of persecution who has been exonerated. Unlike much of the impeachment trial, that performance will be squarely in prime time.

This post has been updated throughout.