Alarms from Congress over the last few days about the president’s refusal to keep lawmakers in the loop as he launched airstrikes that killed Iranian general Qasem Soleimani sparked a push from Democrats to rein Trump in via congressional resolution.

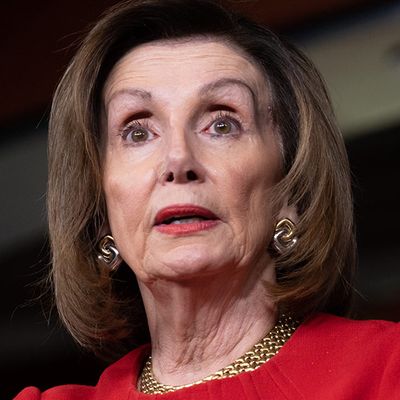

“This week, the House will introduce and vote on a War Powers Resolution to limit the President’s military actions regarding Iran,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced on Sunday. “It reasserts Congress’s long-established oversight responsibilities by mandating that if no further Congressional action is taken, the Administration’s military hostilities with regard to Iran cease within 30 days.”

Pelosi is now planning a vote on January 9. She may be emboldened by a statement made by Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah expressing tentative support for a counterpart Senate resolution by Tim Kaine after he received an unsatisfactory briefing from the administration about its reasons for assassinating Soleimani.

Proclaim as they might that Trump is again out of bounds, congressional Democrats (and the handful of Republicans with longstanding concerns about presidential abuses of power) are not in a good position to do anything about Iran policy. Yes, Pelosi’s War Powers Resolution might pass the House, but that’s probably where it will end unless Trump’s conduct gets so far out of control that the Senate Republican majority preparing to acquit him over articles of impeachment is somehow unsettled.

Here’s everything you need to know about the War Powers Act, including why Pelosi’s move (along with a similar resolution introduced by Kaine in the Senate) may just expose the weak hand Congress has traditionally played in decisions on the use of military force.

Creating the Imperial Commander-in-Chief

The Founders did not deliberately create the imperial presidency as Americans have recently experienced it. But they did, perhaps inadvertently, create an imperial commander-in-chief with broad powers to deploy and direct the armed forces in circumstances (rare enough in the early days of the Republic) that did not require a congressional Declaration of War. It has taken a long series of acquiescent Congresses, however, to make reliance on the presidential powers laid out in Article II of the Constitution a complete alternative to Declarations of War (the last actual declaration was several major wars ago, in 1942).

While Donald Trump is unique in his belief that the Constitution gives him the power “to do anything I want as president,” the notion that Article II gives him virtually unlimited power in many areas of international affairs is much more broadly accepted. In recent years, both Democratic and Republicans administrations have insisted on broad constitutional powers for the commander in chief. Again and again, Congress has granted presidents explicit and often open-ended authorizations to deploy the military without any declaration of war. Presidents, in turn, have exploited these Authorizationa for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs) to conduct wide-ranging operations beyond the scope of the original purpose for seeking such authority, for years and even decades.

War Powers Resolution of 1973

Perhaps the most notable attempt in modern times to reassert some congressional control over military force was the War Powers Resolution (sometimes referred to as the War Powers Act) of 1973, crafted in response to Richard Nixon’s secret military operations in Cambodia and enacted via an override of a presidential veto.

The War Powers Resolution requires that when presidents engage in military actions not authorized by Congress – presumably of some emergency or defensive nature – they notify lawmakers within 48 hours, and bring the military operations to a close within 60 to 90 days (the later deadline applying to withdrawals of forces already underway).

It also provides for a proactive congressional demand for cancellation of an otherwise unauthorized military deployment within 30 days by a simple concurrent resolution. The ability to do this by majority vote was struck down as a collateral effect of a 1983 Supreme Court decision reasserting presidential powers against congressional vetoes, but the procedure itself remains. In fact, this is the provision Pelosi is utilizing, just as opponents of the U.S.-backed Saudi war in Yemen did in 2019, leading to a resolution demanding an end to U.S. support within 30 days which passed both Houses but was vetoed by Trump in April of 2019. Despite some rumblings of limited Republican support for the Pelosi/Kaine measure, it is not going to obtain two-thirds support in either chamber, and certainly not the Senate.

Even if Team Trump accepted the power of Congress to restrain its actions under the War Powers Resolution, his lawyers would almost certainly argue that the attack on Iran falls under a prior congressional authorization.

Authorization for the Use of Military Force

The White House will likely claim that Trump’s Iran-related ventures are in pursuance of the 2001 AUMF, in which Congress basically authorized a global war on terrorism, and the 2002 AUMF, which gave George W. Bush the green light to invade Iraq.

The desire to exploit the 2001 AUMF probably explains the dubious claims emanating from the administration (and particularly from Vice President Mike Pence) that Soleimani was involved after the fact in the September 11 attacks. But as Scott Anderson explains at Lawfare, the 2002 AUMF is the more logical, if still problematic, precedent that might serve as a current authorization:

The 2002 AUMF…authorizes the use of force to address “the continuing threat posed by Iraq” without further elaboration. It provided the legal basis for most U.S. military operations in Iraq from 2003 through the U.S. withdrawal in 2011, including prior military operations against Iran-affiliated militias. Since then, it’s primarily served as a redundant authority for the 2001 AUMF for counter-Islamic State operations in Iraq and, in certain circumstances, in Syria. But it could have broader application. As the acting general counsel for the Defense Department described in 2017 remarks, the 2002 AUMF “has always been understood to authorize the use of force for the related dual purposes of helping to establish a stable, democratic Iraq and of responding, including through the use of force, to terrorist threats emanating from Iraq.” In theory, Soleimani and the other targets of the Jan. 3 strike could qualify as either, due to the Iran-backed PMFs’ history of undermining the rule of law in Iraq and engaging in acts of terrorism targeting U.S. personnel. Moreover, just as the 2002 AUMF authorizes the use of force in Syria where doing so furthers its purpose, it might also authorize the use of military force in other neighboring countries, like Iran.

The political case for using an AUMF on Iraq even in the face of current Iraqi government hostility to U.S. military involvement is shakier, though Americans have never been very good at subordinating sovereign government decisions to our superior second-guessing about their “real” interests, have we?

Congress Passed Up Its Last Chance to Place Limits on Trump

There was a recent opportunity to attempt to impose some restraint on the Trump administration’s military operations against Iran, as part of the debate over a regular Defense Authorization bill (known as the National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA). Last July the House passed an amendment to the bill drafted by Represenatatives Ro Khanna and Matt Gaetz aimed at requiring prior congressional authorization for any attack on Iran, as reported by Vox’s Tara Golshan:

Lawmakers passed two amendments to the House’s more than $730 billion national defense budget that would restrict Trump’s ability to go to war with Iran without congressional approval, and also put a check on Trump’s relationship with Saudi Arabia, an alliance the administration has been using to escalate tensions with Iran.

These amendments were passed with bipartisan support in the House, as lawmakers of both parties grow increasingly concerned about how much power the executive branch wields in the US’s decisions about war. But they will see major resistance among Senate Republicans, who so far have largely supported giving Trump unfettered war authority when it comes to Iran. Trump has already threatened to veto the House version of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). His administration requested $750 billion for the Pentagon budget — a figure Senate Republicans passed late last month.

Fifty senators voted for a similar amendment on Iran, but that didn’t meet the chamber’s super-majority requirement, much less reach the two-thirds vote necessary to override the threatened presidential veto. And so the Iran language was dropped in the final version Trump signed.

It would have taken either unprecedented Republican defiance of Trump, or a bicameral Democratic determination to stall “must-pass” legislation perpetually over what was then a hypothetical fear of Trump lashing out violently at Iran. But it was probably as close as Congress has come – or may come in the immediate future – to reclaiming war-making powers from Trump.

Note: this piece has been updated and corrected to make it clear that the present War Powers Resolution action in Congress is pursuant to a provision in the original WPR of 1973.