When the origin story of Bernie Sanders, the increasingly clear favorite to win the Democratic nomination for president, is told, inevitably, the Brooklyn Dodgers come up. Sanders’s beloved Dodgers left Brooklyn in 1957, when Sanders had just turned 16 years old, because real-estate tycoon and Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley refused to accept a city-owned, city-funded stadium in Queens and decided to move his team to Los Angeles. The move broke the hearts of generations of Dodgers fans, but for Sanders, the story goes, it was more than that: It soured him on capitalism as practiced by the ultrawealthy. “When you’re a kid and the name of the team is called the Los Angeles Dodgers or the Brooklyn Dodgers, you assume that it belongs to the people of Los Angeles or Brooklyn,” Sanders told the Los Angeles Times two years ago. “The idea that it was a private company who somebody could pick up and move away and break the hearts of millions of people was literally something we did not understand. So it was really a devastating moment. I remember it with great sadness.” Former Obama chief strategist David Axelrod had Sanders on his podcast back in 2016 and asked him straight up, if the Dodgers’ move turned Sanders against corporations. Sanders laughed. “I wouldn’t say that was the only thing,” he said.

But, as Sanders potentially closes in on the nomination, it is perhaps worth looking more closely at another, more formative sports moment in Sanders’s history, one that speaks to what he believes, what he hopes to accomplish, and what happens when his ideals conflict with the often gnarled and mean world of capitalism: his experience with the Vermont Reds.

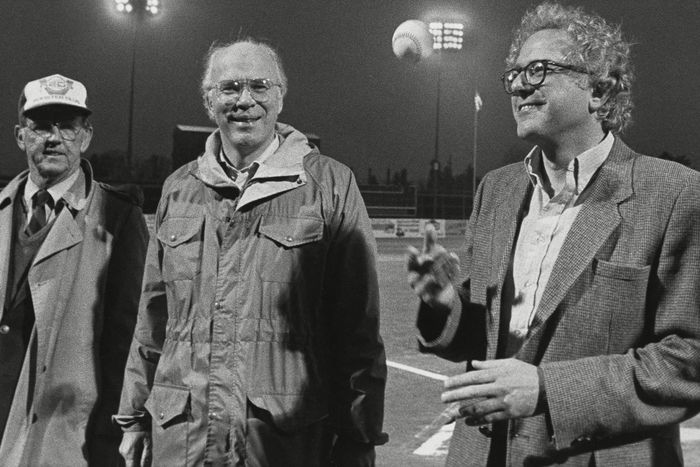

Shortly after becoming mayor of Burlington, Vermont — famously winning by only ten votes — Sanders decided that he should try to bring a minor-league baseball team to town. (This detail, and many others in this column, come from a terrific story by the Guardian’s Les Carpenter back in 2015 that you should definitely read.) True to form, Sanders at first wanted the team be publicly owned, imagining a system like Green Bay’s Packers, which is owned by the city’s citizens. (“It would have been a new model of sports ownership,” one of Sanders’s friends said of the plan.) It turned out, though, the league the team would have played in didn’t even allow this, so he and others in Burlington had to retreat from the original plan.

(It is worth noting, by the way, that while Packers shares are commonly thought of as a public investment, they are, in fact, anything but; as The Wall Street Journal put it, Packers shares “pay no dividends, benefit from no earnings, aren’t tradeable and have no securities-law protection.” They are essentially worthless, yet were sold for $250 a share back in 2011, allowing the Packers to put in a new HD-video scoreboard without having to pay for it themselves. Packers stock is basically a keepsake with voting rights.)

So, like any mayor of any town that wants a sports team, Sanders had to lure a rich guy to either start a team or relocate the team he already owned.

He found the answer, like many mayors who want a team, in public subsidies. A man named Mike Agganis owned the Lynn Pirates, a double-A affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates in Lynn, Massachusetts, and, hearing that Sanders was desperate for a team, met with the young mayor. Agganis told Carpenter in 2015, “He was very aggressive.” Sanders now (quite reasonably, and correctly) lambastes public financing for sports teams, but in the ’80s, eager to get a team, he bent over backwards for Agganis. There was no bond measure or new tax, but Sanders got the public University of Vermont to lease their baseball stadium to the team, and he worked closely with local business leaders to pay for renovations to the stadium, which was more than 80 years old.

The sweeteners persuaded Agganis to move the team from Lynn, and, by all accounts, the team, now called the Vermont Reds (Carpenter notes that there were many Red communist jokes involving the socialist mayor) and later the Vermont Mariners, was a massive success. On the field, it won multiple championships, thanks largely to the Reds’ and Mariners’ farm systems at the time, which included future Hall of Famers Ken Griffey Jr. and Barry Larkin. Of the field, the team was such a fixture of the community that Sanders still uses it as an example of what minor-league baseball can do for small towns, in the wake of Major League Baseball’s ongoing battle with some of its minor-league affiliates. “Families could come to a ballgame —tickets are seven, eight, ten bucks — you get a couple of hot dogs, you have a great evening,” Sanders told Sports Illustrated in December. “Kids can go out near the field, get autographs from players, it was a real boost for the community.”

But here’s the thing about persuading a rich guy to move his team to your town: He can always just move it somewhere else. And that’s exactly what Agganis did. After just four seasons — the minimum time span he committed to stay in Burlington — Agganis moved his team to Canton, Ohio, for “a better market and a brand new stadium,” which the city of Canton built for him. ”Our attendance has averaged out to about 85,000 over five years in Burlington,” Agannis told the Times in 1988. “In Canton, we can probably do between 225,000 and 300,000 attendance.” Sanders fumed and fumed — “He was angry with me,” Agganis told Carpenter — but the owner simply decided that he could make more money elsewhere and therefore left to do so. Sanders could make all the pleas he wanted to his better civic angels, or argue that he was working with a “new model” of sports ownership. But when the rich guy wanted out, the rich guy got out.

Sanders’s efforts were not a total loss, far from it. There is, after all, a minor-league team in Burlington today, in that same stadium they remodeled for Agganis, home to Vermont’s college team and the Vermont Lake Monsters, a short-season, class-A affiliate of the Oakland A’s. Of course, that team was once the Jamestown Expos, until a Burlington businessman named Ray Pecor bought them and moved them to his town. (Most teams used to be somebody else’s team.) And even that team is in danger now — it’s one of the teams that MLB is threatening to unaffiliate, potentially putting them out of business. The Lake Monsters are why Sanders elbowed into that mess in the first place, even meeting with MLB commissioner Rob Manfred about the issue.

And it does feel like there is a lesson in here somewhere, or at least a potentially illustrative example. Sanders, in some ways wanting to right a wrong from his childhood while supporting his community through collective action, attempts to create a new paradigm involving civic engagement and working outside the traditional capitalist system, is thwarted at every turn and is forced to find more traditional ways to help out his constituents. He succeeds, only to have his task undone by the whim of a wealthy man. And yet, Sanders lays the groundwork for something to succeed long term, until another billion-dollar corporation, Major League Baseball, threatens to shutter it for the same purely capitalist reasons he’s been fighting against all this time. Sanders has a long history with sports, from his remarkably fast times as a long-distance runner to his long history with basketball all the way up to supporting sports website Deadspin (which, full disclosure, I founded) when its whole staff resigned while battling its new private equity owners. But the story of Bernie Sanders and sports, in many ways, is the story of Bernie Sanders in total, for better and for worse. And it always seems to be the same story, over and over.