For most of Tuesday morning, no one knew anything, and Bernie Sanders was nowhere to be seen. Ten, then 12, then 15 hours after the Iowa caucus results were initially expected, the senator (the front-runner?) was still in Des Moines, avoiding the cameras and waiting for some answers on what exactly happened Monday night.

While Sanders sat and his senior team members stewed, fretting that their deserved momentum was slipping through their fingers, his rivals fanned out across New Hampshire. Joe Biden’s campaign mobilized lawyers to question the caucuses’ legitimacy. Elizabeth Warren took the stage in Keene, promising to fight on, and Pete Buttigieg made two stops in the state’s southern tier, flooding the morning TV-interview circuit to keep declaring victory, even with no official count to back up the claim. Yet there was Sanders, still on midwestern ground, saying nothing. Behind the scenes, his inner circle had been convinced since early the previous night that he’d won. But it was also growing increasingly clear to them that he’d get no glowing moment in the spotlight anytime soon — and that the polling bounce he would typically expect from a kickoff win might never come, thanks to developments that were out of their hands. Would they even be declared the winner before Tuesday night’s State of the Union address?

The morning aged, Sanders’s silence grew more notable, and rumors flew about when the Iowa state party would say something, anything, official. Sanders’s senior adviser Jeff Weaver, his 2016 campaign manager and longest-serving aide, tried to pry whatever information he could get out of the party operation. When its chairman, Troy Price, finally convened a call with flabbergasted representatives from the campaigns at 11 o’clock local time, he informed them that, later in the afternoon, the party would release the results it had from over 50 percent of precincts but not a final total. Aides from rival campaigns objected, unwilling to settle for an incomplete count. Sanders’s allies sighed, exasperated, but Weaver acknowledged he’d been hard on Price the previous night and said at least they were getting some results out. “The criticism of the integrity of the process is coming from folks who didn’t fare too well in the caucuses,” he told me after. It seemed clear he was talking about Joe Biden.

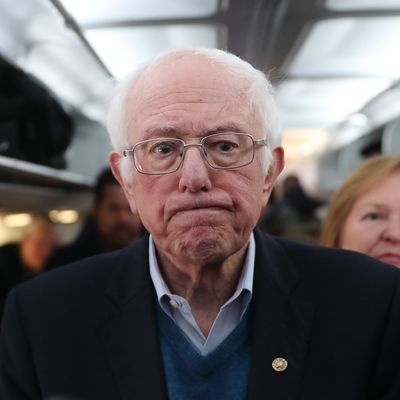

If the tide wasn’t going to turn on its own, they’d have to turn it themselves, and Sanders would have to be on the ground in New Hampshire when the results landed. So there he finally was on his chartered campaign plane on the Des Moines tarmac, shortly after noon. Flanked by his wife and the top echelon of his campaign team, he approached a small group of reporters jammed halfway down the narrow central aisle. An aide whispered to him that he’d have to speak up to be captured by the mics over the engine’s thrum; as he neared, the plane revved up, and the flight attendants suddenly made their boarding announcements. “Never before in history have so many cameras been on an airplane,” Sanders said, surveying the scene. It was clear to him, and to anyone who’d been there, that this midday flight to New Hampshire would likely be a far cry from the overnight party plane four years earlier, when he’d nearly claimed a shock victory over Hillary Clinton and kicked off the big-time phase of his political revolution. But this time around, it wasn’t just a lack of results standing between Sanders and a big night for fundraising and political momentum. Even if Sanders’s internal numbers were right and Biden was in serious trouble, Buttigieg looked perilously close, and progressive rival Elizabeth Warren likely wasn’t going anywhere.

Almost immediately, Sanders said he wouldn’t be declaring victory yet, but he insisted he was feeling good about the internal numbers his team had seen. Asked about Buttigieg’s claims of a win — backed by initial data from the mayor’s team — Sanders raised his eyebrows and shot back, “I don’t know how anybody claims victory without an official statement of election results. I’m not declaring victory.” He then introduced Weaver to effectively declare victory.

The adviser shared that the campaign’s updated numbers showed Sanders ahead of Buttigieg, with Warren in third and Biden and Amy Klobuchar far behind. As Weaver spoke, campaign manager Faiz Shakir sent an email to supporters, informing them, “Our internal results sent to us by precinct captains around the state indicate that with close to 60% of the vote in, we have a comfortable lead.” Still, Sanders looked around but didn’t smile. He seemed more focused on the point at the top of Shakir’s email: “Last night was a bad night for democracy, for the Democratic Party, and for the people of Iowa.”

Less than two hours after Sanders touched down in New Hampshire, the party finally released some initial results: Buttigieg was ahead but barely, and Sanders had — as his team had long hinted would happen — won the first alignment. Still, the night was young, and nearly 40 percent of precincts had yet to be counted. “We want to thank the people of Iowa,” Weaver said in a statement. “We are gratified that in the partial data released so far, it’s clear that, in the first and second round, more people voted for Bernie than any other candidate in the field,” a line Sanders echoed Tuesday night at his Milford, New Hampshire, rally.

For most of Caucus Day, Sanders’s team was encouraged by what it was seeing. They were happy with the optics of the first satellite precinct to report its results in the afternoon: Of 15 caucusgoers at the Ottumwa location, 14 — primarily Ethiopian immigrants who work at the local pork-processing plant — went for Sanders. And when the night’s main-event caucuses started in earnest, they had a good feeling early. Aides said on Tuesday that after about 15 percent of their precinct captains had reported totals back to HQ early the previous evening, their numbers (showing Sanders in first and Buttigieg in a tight second, with Warren close) stayed roughly steady. When all was done, there was anecdotal reason for cheer, too, which played right into the Sanders team’s claim that it was turning out disaffected and new voters, including Latinos. Advisor Chuck Rocha celebrated that, of the 483 Iowans who caucused in the state’s four Spanish-language satellite caucus sites, Sanders earned all the delegates, winning the support of 430 voters.

But a central piece of Sanders’s plan to win the nomination had always been a clear win in Iowa, and as Monday evening went along, it was hard to miss the troubling signs that the contest was looking tight. Most data that became available throughout the day, including Sanders’s own, didn’t show him expanding his support much between the caucuses’ first and second alignments, perhaps casting doubt on his long-term ability to build upon his base within the party. (In the initial results dump, it was Buttigieg who gained more ground after the first round.) And for a candidate who speaks constantly of the need for a massive voter turnout to propel him to victory, the apparent drop back to 2016 turnout levels, instead of the 2008-style surge many Iowans predicted, was discouraging too.

All day long, Sanders aides had been popping up around Des Moines expressing confidence but refusing to say much of substance on the record, instead waiting for the big evening moment when they thought he’d get to celebrate. In the press filing center at Sanders’s Caucus Night party, deputy campaign manager Ari Rabin-Havt walked in around the time caucus sites opened and was immediately swarmed by reporters. He didn’t want to talk about what Sanders was doing or how he was feeling. “I got nothing here!,” he insisted. And when asked if anything could stop Sanders’s run to the nomination if he won Iowa, Rabin-Havt stood straight and replied, “I’m not—, I’m not—, I’m not—,” before turning around and knocking on a wooden table three times.

About an hour later, California congressman Ro Khanna, a Sanders campaign chairman, downplayed the idea that Iowa could set the candidate on a glide path. “It’s a long process to the nomination,” he insisted to me on the sidelines of the party. “I don’t think he’s under any illusion that this isn’t a long slog, and he views himself as an underdog taking on a lot of special interests.” He allowed, though, that he’d seen a surge in support for Sanders since he came out strongly against war with Iran earlier this year and got the formal endorsement of the Sunrise Movement environmental group, all positioning him “for a good showing in New Hampshire.”

As the night dragged on and it became clear that something was going wrong, the attendees cheered less enthusiastically each time CNN showed Sanders’s empty lectern. Meanwhile, the fully stocked cash bar in the next room over got more and more crowded. Aides grew hesitant about walking through the press area. One, trying to move away from the main stage, found himself surrounded by journalists trying to see if he had any idea what the reporting delay was all about. He looked around, overwhelmed. “This is fun, this is fun,” he said under his breath, and kept walking.

The mood of the room shifted palpably after the campaigns were told there were real problems with the caucus results and Klobuchar jumped at the opportunity to speak first, before East Coasters went to sleep. Warren and Biden’s campaigns both said their candidates would talk soon, too, and suddenly Sanders staffers began hustling around the room to fill the risers behind the lectern, where — surprise! — the senator would soon appear. He took the stage, insisting he was happy with what he’d seen, declaring the end of Trump was near, and promising to march on. He almost accidentally quoted Howard Dean’s infamous 2004 exclamation (“Now it is on to New Hampshire!,” Sanders said, “Nevada! South Carolina! California! And onward to victory!”), but no one noticed amid the madness of the moment. He left the stage, but his campaign — still sure good news would come soon — asked supporters to stay tuned.

Of course, looming doubt about the final result remained. “Any campaign saying they won or putting out incomplete numbers is contributing to the chaos and misinformation,” tweeted Joe Rospars, Warren’s chief strategist, later that night, as Buttigieg’s camp distributed numbers suggesting he’d won, Warren’s campaign manager said they expected a close three-way race with Biden far behind, and Klobuchar’s campaign manager said her candidate would be close to Biden. The initial results released Tuesday were friendlier to Buttigieg than to Warren.

Still, Sanders still could hardly contain his disappointment half a day later as he spoke to reporters on the chartered plane and insisted he’d likely won. Asked about Biden’s posture toward the caucuses, he replied, “We should all be disappointed in the inability of the party to come up with timely results. But we are not casting aspersions on votes that are being counted.”

Calling the state party “negligent,” Sanders admitted, “Frankly, I am disappointed — and I suspect that I speak for all the candidates, all their supporters, and the people of Iowa — that the Iowa Democratic Party has not been able to come up with timely election results. I can’t understand why that happened, but it has happened.”

He was minutes away from wheels up to New Hampshire, the state that gave him his most resounding victory in 2016 and could do so again in a week. He was again the front-runner. But, Sanders said, “this was not a good day for democracy.”