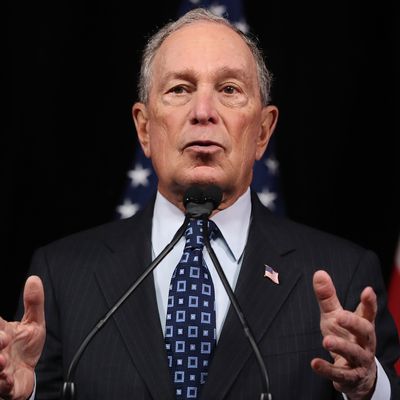

Michael Bloomberg was, until a couple months ago, one of America’s leading advocates for racially discriminatory policing, financial deregulation, and slashing Social Security and Medicaid benefits. The 77-year-old billionaire has an undisputed history of making sexist remarks to female subordinates and three active sexual-harassment lawsuits pending against his company. He endorsed George W. Bush at the 2004 Republican National Convention; campaigned with Rudy Giuliani in 2009; and spent $11.7 million on helping a pro-life Republican senator narrowly defeat a female Democratic challenger in Pennsylvania just four years ago.

In 2014, Bloomberg gave $3 million to Michigan governor Rick Snyder, the conservative Republican who presided over the mass poisoning of Flint’s water supply. The supposedly “socially liberal” billionaire’s rationale for backing a self-described “pro-life, pro-Second Amendment” Republican? Snyder was, in Bloomberg’s words, a guy “who took on the unions to get Detroit and Michigan going in the right direction. And he was re-elected despite being attacked by the unions.”

In other words: Michael Bloomberg has spent much of the past two decades publicly voicing contempt for core Democratic constituencies (young nonwhite people, professional women, the poor, and labor unions) while undermining their policy priorities (flouting civil liberties protections for marginalized groups, bankrolling pro-life Republicans, championing draconian safety-net cuts, and lavishing praise on right-to-work laws). Meanwhile, the billionaire has also committed myriad affronts against Democrats as Democrats — not least, by opposing the party the last time it tried to prevent a lawless GOP president from renewing his lease on the White House.

Nevertheless, he is now one of the top contenders for the Democratic Party’s 2020 nomination. Since December, Bloomberg has gained 15 points of support among Democratic primary voters, enough to propel him into second place nationally, according to a new NPR/PBS/Marist poll. Another survey released Tuesday shows Bloomberg tied with Bernie Sanders for first place in Virginia’s primary. Polls of other Super Tuesday states have found the mogul surging into contention.

There are many reasons why Bloomberg has managed to overcome his unsightly résumé — 419 to be precise. The first 418 reasons consist of each individual million-dollar investment he has made in campaign advertisements, as part of a propaganda blitz without contemporary peer or historical precedent. The other reason is that Democratic voters value “electability” in their 2020 standard-bearer above all else.

If the 2020 primary were a fight over values, records, or sheer popularity among longtime residents of “blue America,” Michael Bloomberg wouldn’t have a prayer. Well-heeled moderate Democrats in the tristate area may have a genuine fondness for the man. But they account for a negligible fraction of the party’s primary electorate. Bloomberg has made himself competitive by martialing his mind-bogglingly vast fortune behind the message: “The only thing that can stop a bad billionaire with a giant campaign war chest is less bad mega-billionaire with a gargantuan campaign war chest.”

Mike Bloomberg is only electable if the 2020 election is buyable.

From most angles, the concept of “Mike Bloomberg, electability candidate” looks bizarre. The mogul is a short, 78-year-old non-Christian who speaks in a nasally monotone; all characteristics that no winning presidential candidate in the modern era has shared. And Bloomberg’s eccentric qualities aren’t merely superficial. He is an unabashed elitist who has publicly argued 1) that ordinary Americans can’t be trusted to pick their own soda size, and 2) that, while he could “teach anybody to be a farmer” or an industrial worker, the modern information economy demands a level of skill and “gray matter” that is much more difficult to inculcate in the average human being.

Meanwhile, nominating Bloomberg would potentially cost the Democratic Party two of its most precious electoral assets: Its status as the party voters trust most to protect entitlements, and (relatedly) its standing as the party that puts the interests of ordinary people above those of the wealthy. Bloomberg may occupy the center of the ideological spectrum within CNN greenrooms, Wall Street C-suites, and Davos after-parties — but in America as a whole, the “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” species of moderation that he has championed for most of his adult life is a rare breed.

Finally, Bloomberg is singularly toxic to the Democrats’ grassroots activists and labor groups. Yes, Joe Biden has committed no small number of sins against progressive orthodoxy. But Uncle Joe’s worst deeds aren’t nearly as recent or severe as Mike’s. Six years ago, Biden was not working to reelect an anti-choice Republican governor on the grounds that destroying Detroit’s unions was more important than protecting Michiganders’ reproductive rights or the city of Flint’s water supply. Biden went to bat for the big banks in the Senate in the early aughts; but he didn’t sic cops on Occupy protesters and progressive journalists less than a decade ago. Bloomberg would do far more than any other potential Democratic nominee to demobilize progressive activists, increase the Green Party’s vote-share, and accelerate the rightward drift of certain predominately white trade unions in the Midwest’s Rust Belt battlegrounds.

And yet, Bloomberg has nevertheless managed to convince a large and growing chunk of Democratic voters that he is, in fact, their safest bet. That Bloomberg’s exorbitant ad-spending has proven sufficient to sell voters on this idea — despite its facial implausibility — is ironically the strongest argument for the idea’s validity. Which is to say: The fact that Bloomberg has bought himself an aura of electability, against long odds, suggests that he just might be able to buy himself a general election victory, too.

Conventional wisdom holds that in an ultra-high-visibility presidential election, campaign spending eventually hits a point of diminishing returns. Hillary Clinton greatly outspent Donald Trump in 2016, after all. But Clinton’s campaign outspent Trump’s by a mere $768 million to $398 million. Mike Bloomberg is worth roughly $60 billion. Between his ad-spending and tactical donations to Democratic interest groups and down-ballot candidates, Bloomberg has already invested more than half-a-billion dollars into his long-shot primary campaign. Imagine what the 78-year-old mega-billionaire would be willing to spend were he a single election away from commanding the world’s most powerful state. No one actually knows what a $10 billion general-election campaign would look like, nor what political realities it could or could not change.

The mainstream media seems to have a soft spot for cosmopolitan plutocrats.

Bloomberg’s general election campaign would not only benefit from an unprecedented avalanche of paid media; it would also likely enjoy generous coverage from the mainstream political press. Bloomberg not only commands his own news media empire, but embodies a cosmopolitan, center-right worldview that is popular with a significant segment of cable news executives and talking heads.

To see one (arguable) illustration of the charity that Bloomberg enjoys from the Fourth Estate, consider this following sequence of events:

1) On Sunday night, Wisconsin’s Republican Party promoted a 2016 clip of Bloomberg telling students at the University of Oxford:

I could teach anybody, even people in this room so no offense intended, to be a farmer. It’s a process. You dig a hole, you put a seed in, you put dirt on top, add water, up comes the corn. You could learn that … Then you have 300 years of the industrial society. You put the piece of metal on the lathe, you turn the crank in the direction of the arrow and you can have a job. And we created a lot of jobs. At one point, 98% of the world worked in agriculture; today it’s 2% in the United States. Now comes the information economy, and the information economy is fundamentally different because it’s built around replacing people with technology … You have to have a lot more gray matter.

2) The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel reached out to the Bloomberg campaign before writing up the candidate’s remarks. And the campaign provided the paper with a supposedly (but not actually) exonerating bit of context. As the Journal-Sentinel reported:

In the video circulated on Twitter, Bloomberg says: “I could teach anybody, even people in this room so no offense intended, to be a farmer. It’s a process. You dig a hole, you put a seed in, you put dirt on top, add water, up comes the corn. You could learn that.”

But the video deleted the first part of that statement, in which Bloomberg says, “if you think about the agrarian society (that) lasted 3,000 years, we could teach processes.”

3) Blake Hounshell, the editorial director of Politico, tweeted out the Journal-Sentinel’s story, writing, “Bloomberg was insulting farmers from 3,000 years ago, not modern farmers.”

Note: The only mitigating context the Bloomberg campaign could muster was a fragment that does not actually change the plain meaning of the billionaire’s remarks in any way. In the video that the Wisconsin GOP posted, it is clear that Bloomberg is discussing a progression from an agricultural age to an “industrial society” to an “information economy.” He cites this progression to argue that it is more difficult to find valuable labor for low-skill (and/or, low “gray matter”) people to perform in the modern era than it was in previous epochs. Bloomberg then explicitly invokes modern farmers, saying, “At one point, 98 percent of the world worked in agriculture; today it’s 2 percent in the United States.” He does not then add, “and the work modern farmers do is actually quite sophisticated.” His clear implication is that, while there is still some farming work for simpletons to perform, there is much less of it than there used to be.

Maybe in the full video of Bloomberg’s lecture, the billionaire clarifies that he has nothing but esteem for the intellectual capabilities of contemporary farmers and industrial workers. But in the Journal-Sentinel’s write-up, the only evidence offered for the assertion, “Bloomberg was not insulting modern farmers” is that a Bloomberg campaign representative said that he wasn’t.

And yet, the editorial director of America’s preeminent online political news publication endorsed the campaign’s spin unequivocally. And not only that — his instinctual credulity toward the Bloomberg campaign ostensibly led him to favorably misread phrase “the agrarian society (that) lasted 3,000 years” as “the agrarian society (that) ended 3,000 years ago.”

I don’t mean to pick on Hounshell. I consider Politico an indispensable resource, and he’s clearly done a fine job directing many aspects of its operation. We’ve all posted bad tweets. But it seems unlikely to me that he, or others similarly positioned, would have missed the thinness of Team Bloomberg’s spin in this instance, had it come from the Sanders campaign instead.

Thanks to the combination of Bloomberg’s heavy-spending, cable news’ favorable treatment of his candidacy (even as he’s declined to compete in the first several primary contests), and the aura of “moderation” that these have conveyed to the mass public, the billionaire currently polls about as well against Donald Trump as any other Democratic candidate. It is hard for me to imagine Bloomberg’s numbers holding up under scrutiny. But then, as already mentioned, it’s also hard to imagine what a multibillion-dollar general election campaign looks like.

The case for Bloomberg is weak and bleak.

So, it’s conceivable that Bloomberg could, in fact, buy himself the presidency. And once in office, his personal fortune could theoretically enable him to overcome other seemingly insurmountable political obstacles. In February 2021, Bloomberg will turn 79. What would a man with more than $50 billion — and only a few years left to live — be willing to spend on securing a legislative legacy? Is it inconceivable that Bloomberg could expand the boundaries of political possibility in the Senate, by promising the Joe Manchins and Lisa Murkowskis of the world giant dark money campaign contributions (and/or, extraordinarily lucrative sinecures for their family members at a Bloomberg enterprise of their choice) if they do his bidding? Can $2 billion in bribes buy president Bloomberg a more ambitious climate law than any other Democrat could hope to pass?

This is the honest case for Michael Bloomberg. It is an argument for Democrats to accept that the best that they can hope for in 2020 is benevolent plutocracy: There is no campaign capable of defeating Trumpism through organizing and reasoned argument, so best to let a billionaire drown it in an ocean of propaganda; there’s no mass movement capable of breaking through D.C.’s gridlock, so let’s see if Lisa Murkowski has a price.

I can’t tell you that this case is wrong. But I can say that we have little reason to believe that it is right.

Maybe Bloomberg’s money can bend our political system to his will; or maybe no amount of advertisements can convince Rust Belt swing voters to support a historically uncharismatic candidate who disdains their “gray matter.” Maybe president Bloomberg would use his awesome, unaccountable financial power to get sweeping climate legislation through the Senate; or maybe he’ll use it to gut the social safety net. Maybe casting our lot with our team’s racist, misogynist, instinctually authoritarian billionaire will save our democracy by keeping the ethnonationalist right out of power just long enough for its voting base to die off; or maybe doing so will extinguish the possibility of achieving genuine popular self-rule in the United States, as Bloomberg’s success inspires a series of super-rich imitators until we all become the subjects of Supreme Leader Bezos.

All we know is that we do not know. And if rallying behind the better of two plutocrats isn’t even guaranteed to “work,” on its own terms — if, to the contrary, there are many reasons to believe it would fail — why on Earth would we make that bet? Why roll the dice on beneficent oligarchy when social democracy looks like (at least) as safe a gamble?