It took only a few hours after Rashida Tlaib booed a mention of Hillary Clinton while onstage at a Bernie Sanders campaign rally in Clive, Iowa, on Friday before she backed down. “I know what is at stake if we don’t unify over one candidate to beat Trump and I intend to do everything possible to ensure that Trump does not win in 2020,” tweeted the Michigan congresswoman — she was just disappointed with Clinton’s recent questioning of Sanders’s effort to unite Democrats in 2016, she said. The cleanup was swift, and it was on message: The morning after the boo, Sanders reminded a rally crowd in Indianola that he was friends with the other candidates, and that “if we do not win, we will support the winner, and I know every other candidate will do the same.”

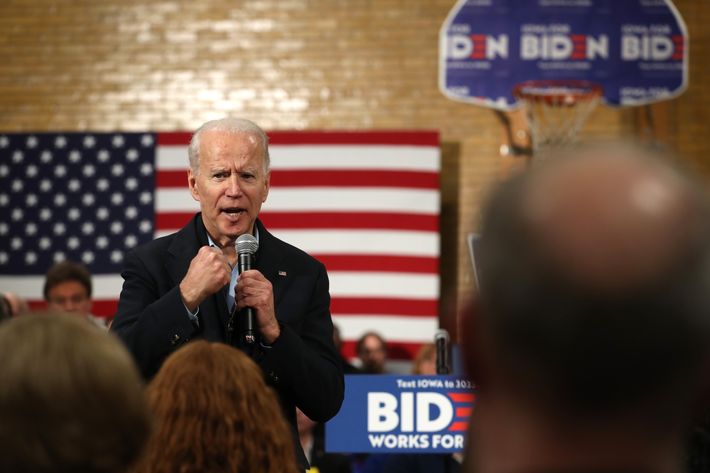

This wasn’t a new line from Sanders, but coming just as each candidate is straining to prove that he or she can beat Trump, it was an especially pointed one: In order to win the nomination, after all, Sanders will need former Clinton supporters on his side. And he’s not alone. In the closing hours before Monday’s Iowa caucuses, Elizabeth Warren is making her most explicit unity pitch yet, aiming to prove that firing up dedicated progressives is only part of her plan and that she represents the party’s 2020-era center. Meanwhile the two leading candidates who have most often spoken of the need to unify the entire country, not just the party — Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg — have each been amplifying their criticisms of their rivals, feeling the imperative to underscore the contrast for undecided Iowans, many of whom want reassurances that they’ll be ready to fight Trump head-on.

While those around Warren have long suggested that her ideological vision and plans position her well to bring the party’s factions together, her surrogates only started saying this out loud in so many words in recent weeks. Upon returning to Iowa from the impeachment trial this weekend, Warren herself joined in. “We will, we must come together to defeat Donald Trump,” she said in Cedar Rapids on Saturday, a few hours before brushing off a question about Tlaib in Iowa City: “In the primaries, people can get heated. But what’s important is we come together as a party. Because we have one really important job, and that is to beat Donald Trump.” In Cedar Rapids, she tried to prove the point by listing the former candidates whose onetime staffers have since joined her campaign (Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Julián Castro, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Steve Bullock), and in Iowa City her introduction included one of the state’s most prominent Sanders 2016 supporters and one of its best-known Clinton 2016 backers. In case that wasn’t enough, the campaign started distributing new signs that said, simply, “UNITE THE PARTY.”

Buttigieg, meanwhile, has often spoken of his wish to win over “future former Republicans,” especially in the parts of the state that went for Trump in 2016 after backing Barack Obama. But in the closing stretch, he’s also leaned further into his central pitch about generational change even within the Democratic Party, often emphasizing, “This is no time to get caught up in reliving arguments from before,” and “The less 2020 resembles 2016 in our party, the better.” In recent days, this looks more like a shot at Sanders than ever. “I hear Senator Sanders calling for a kind of politics that says you’ve got to go all the way here and nothing else counts,” Buttigieg has taken to saying, making the case that such a posture excludes moderates and Iowans who are curious about Democrats but not convinced. Yet the former mayor also felt heat from Biden, whose recent ad campaign insisting that now is no time to take a risk was partially targeted at voters deciding between the two of them. “I hear Vice-President Biden saying that this is no time to take a risk on someone new. But history has shown us that the biggest risk we could take with a very important election coming up is to look to the same Washington playbook and recycle the same arguments, and expect that to work against a president like Donald Trump, who is new in kind,” Buttigieg replied in Decorah on Thursday.

For his part, Biden sees little upside to directly going after Buttigieg, clearly believing his initial line worked and that wavering voters got the message. Still, his allies bristled at his opponent’s suggestion: “With all due respect to the mayor, that’s not how this process works. You don’t walk in and basically say, ‘I’m now elected, and this is the way it’s going to be.’ We’ve seen what that’s like with President Trump,” Biden’s top Iowa surrogate, former governor and Agriculture secretary Tom Vilsack, told me after the former vice-president spoke in Waukee last week. “Anybody who suggests that somehow you don’t need a lot of experience to navigate the world just doesn’t quite understand. On any given day, the president will be dealing with a pandemic in Asia, a cyberattack in Europe, a terrorist attack in the Middle East, and gun-violence activity here. I mean, you have to be able to pick up the phone, and when you’re talking to a world leader, that world leader needs to know who you are.”

Biden, though, did briefly venture further into Sanders criticism than he has in months last week, while making a final push among older voters deciding between the two of them. He called the contrasts between them “self-evident,” pointing out, “I’m a Democrat,” before bringing up Sanders’s “record on guns”: “The fact that he gave the gun manufacturers an exemption that no other, no other industry in the world — in the United States — has, I think he regrets having done that.” As Biden amped up his pressure on Sanders, the election cycle’s first Democrat-on-Democrat attack ad was starting to play in the state, questioning Sanders’s general-election viability and even mentioning his recent heart attack. Sanders, who was in Washington for the impeachment trial at the time but soon returned to Iowa, never personally responded to Biden’s comments, eager not to muddy his closing message.

Of course, the candidate’s own insistence on staying on the unity message hasn’t stopped his campaign from leaning into at least some of the fights. After Tlaib tweeted her apology, Sanders’s campaign manager replied, “Rashida, you’re all good. We love your passion and conviction. Don’t change.” A few hours later, opening the programming at Sanders’s concert rally in Cedar Rapids — the cycle’s single biggest Iowa event — filmmaker Michael Moore led the audience in a series of chants against Michael Bloomberg and the Democratic National Committee.