In his State of the Union address Tuesday night, Donald Trump touted his support for Medicare, Social Security, price controls on prescription drugs, regulatory protections for people with preexisting conditions, new infrastructure spending, paid family leave, environmental protection, increased federal funding for child care, rural broadband, criminal-justice reform, and the cultivation of an “inclusive society” in which Americans of “every race, color, religion, and creed” can thrive.

He also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to a talk-radio host who has argued that “feminism was established so as to allow unattractive women easier access to the mainstream of society”; derisively referred to public education institutions as “government schools”; and described various homicides committed by “illegal aliens” in grisly detail as part of a transparent effort to stoke fear and loathing for one of America’s most vulnerable minority populations.

In other words, he struck a “moderate” tone.

In elite discourse, the terms “centrism” or “moderation” tend to imply a specific, coherent worldview — to be ideologically moderate is to endorse positions that lie somewhere between each major party’s orthodoxy on most issues. But this is not how the median self-identified moderate understands their ideological orientation. In truth, individual “moderates” tend to espouse idiosyncratic grab bags of left and right policy preferences and attitudes, including some that would strike D.C. centrists as radical or reactionary. And there’s some evidence that voters don’t just equate moderation with heterodoxy when describing their own ideological affiliation, but also when they describe those of politicians.

In 2016, Trump campaigned for the presidency on a promise to ban Muslims from the United States, coerce Mexico into financing a wall along America’s southern border, target the wives and children of ISIS terrorists, and imprison his Democratic opponent. And yet, according to Gallup, voters considered him the least conservative Republican nominee in more than a quarter-century. Several factors likely informed this perception. One was Trump’s personal libertinism, which led many secular, white working-class voters with a distaste for the Evangelical right’s moralism to conclude that his professed opposition to abortion was insincere, according to postelection focus groups convened by Planned Parenthood. But another factor seems to have been Trump’s rhetorical embrace of relatively liberal positions on entitlements, prescription drug pricing, infrastructure, and (at times) health care. A Pew Research Survey released in July 2016 found that plurality of voters saying that Trump’s “views can best be described as a mix of liberal and conservative.”

All of which is to say, Trump’s rhetoric is borderline fascistic on many subjects — while his governing agenda is arguably the most uniformly reactionary of any modern GOP president’s — doesn’t necessarily mean that his mendacious gestures of moderation and inclusion Tuesday night won’t prove politically effective.

The discrepancy between Trump’s heterodox campaign rhetoric and exceptionally conservative presidency hasn’t been wholly lost on the electorate. In a January 2017 YouGov poll, 22 percent of voters described Trump as moderate, 11 percent called him liberal, and 42.5 percent said he was conservative. By December 2019, just 6 percent still considered Donald Trump a “lib,” while 16 percent called him moderate, and 49 percent identified him as a man of the right.

But in the latter survey, 57 percent of independent voters either described Trump as a centrist or else could not place him anywhere on the ideological spectrum.

In my view, the significance of how voters categorize themselves and their nation’s presidential candidates ideologically tends to be both misinterpreted and overstated. The incoherence of actually existing moderates’ preferences reflects the irrelevance of ideological categories to many voters. The fact that a slim majority of voters don’t recognize Trump as a conservative, however, does suggest that when the president endorses broadly popular liberal policy ideas, his disingenuousness will not be obvious to a wide swath of the electorate.

This point may sound banal. But in 2016, some Democrats took false comfort in the presumed transparency of Trump’s extremism. Whereas previous Republican nominees had dog-whistled their appeals to nativist and anti-black sentiment, Trump derided Mexican immigrants as a pack of drug dealers and rapists (with some good people sprinkled in) and retweeted white nationalists. These provocations inspired a widespread, bipartisan expectation that the mogul would cost the GOP dearly among nonwhite voters in November. But the prophesied backlash failed to materialize. In fact, exit polls showed Trump performing slightly better with black and Hispanic voters than Mitt Romney had four years prior (such polls are woefully imprecise, but would not have totally failed to register a sea change in nonwhite voting patterns had one occurred). Trump’s affronts to decency and decorum did alienate some suburban white voters, but not nearly as many as Democrats had hoped.

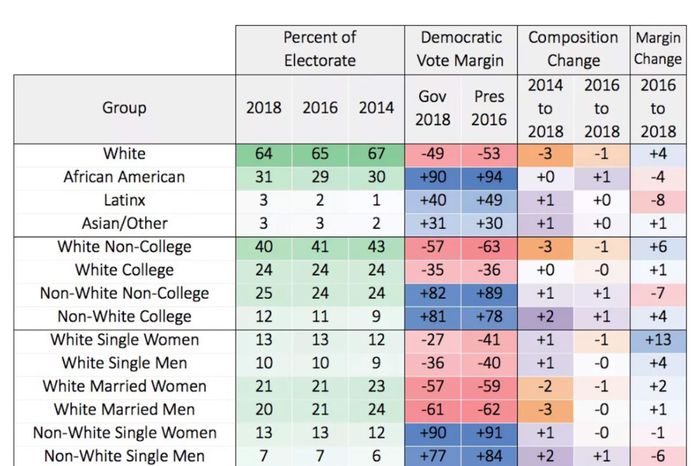

Given this history, liberals would be unwise to laugh off Trump’s recent appeals to African-American voters or his advocacy for high-polling pillars of the progressive agenda. In fact, there is acute cause for concern about the potential efficacy of the former. As Vox’s Matt Yglesias has noted, Democrats actually won a smaller share of the African-American vote in 2018 House races than they had in the 2016 presidential election — even as the party’s overall popular-vote edge in the midterm was 5 points higher than Hillary Clinton’s two years earlier.

Remarkably, this very slight right turn among black voters showed up even in Georgia’s gubernatorial race, which pitted the African-American minority leader of the state’s House of Representatives Stacey Abrams against a secretary of State complicit in voter-suppression efforts. According to the Democratic data firm Catalist, Abrams’s share of the state’s black vote in 2018 was 4 percentage points lower than Hillary Clinton’s in 2016.

More alarmingly, this same modest shift is detectable in early polls of the 2020 general election. In its survey of Electoral College battleground states last fall, the Upshot found all the leading Democratic candidates failing to match Clinton’s 2016 margin among African-Americans.

What makes these scattered data points most concerning, though, is that there is a theoretical basis for expecting the Democratic Party’s share of the African-American vote to erode over the coming decade. Keeping 90-plus percent of any subgroup united in one partisan camp takes work. The reason Democrats have enjoyed such a landslide margin among black voters — despite considerable ideological and attitudinal diversity within that demographic — is not that each individual African-American Democrat concluded that the GOP was hostile to people like them through their own personal ruminations on current affairs. Rather, as political scientists Ismail K. White and Cheryl N. Laird argue in their new book, Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior, the black bloc vote is a product of “racialized social constraint” — which is to say, the process by which African-American communities internally police norms of political behavior through social rewards and penalties. In their account, the exceptional efficacy of such norm enforcement within the black community reflects the extraordinary degree of black social cohesion that slavery and segregation fostered.

If this thesis is correct (and White and Laird do much to substantiate it), then it would follow that the erosion of African-Americans’ social isolation would weaken racialized social constraint, and thus, narrow the Democratic Party’s margin with black voters. As White and Laird write:

We believe that increased contact with non-blacks and a decline in attendance at black institutions, in favor of more integrated spaces, would threaten the stability of black Democratic partisan loyalty. The result, we believe, would be a slow but steady diversification of black partisanship because leveraging social sanctions for racial group norm compliance would become much more difficult in integrated spaces.

The president seems to have arrived at a much less precise version of this hypothesis. His reelection campaign devoted its Super Bowl commercial to heralding Trump’s support for decarceration by spotlighting the criminal-justice-reform bill he signed, as well as the story of an African-American woman named Alice Johnson who was convicted of a nonviolent drug offense and released from prison after Trump commuted her sentence. In his State of the Union address, Trump gave tribute to the last surviving Tuskegee Airman, “the marchers at Selma,” and Martin Luther King; boasted that he is presiding over record-low African-American unemployment, African-American youth unemployment, and African-American poverty; and reiterated his support for criminal-justice reform.

These gestures of outreach are largely fraudulent. Although Trump did indeed sign a modestly progressive criminal-justice-reform bill into law, his Justice Department has been working around the clock to limit its impact on mass incarceration. And while the African-American unemployment rate has hit record lows since Trump took office, there is little basis for attributing this to the president’s policies, except in the limited sense that Trump has done nothing to reverse the steady upward trend in job growth that he inherited. To the extent that Trump’s policies have impacted African-Americans’ material fortunes, the effect has almost certainly been a net negative. His administration has worked to restrict access to food assistance programs and facilitate cuts in eligibility for Medicaid, policies that disproportionately hurt black people. Meanwhile, if the White House had had its druthers, it would have cut $1 trillion in Medicaid funding to finance larger tax breaks for the wealthy.

But the Trump campaign has alternative facts, and it is investing time and money into putting its propaganda in front of as many African-American voters as possible. If Democrats do not recognize the threat that this poses — if the party operates from the presumption that it can take such voters for granted — the African-American community’s political “norm enforcers” may no longer be able to bail them out. Precisely what kinds of messaging and organizing efforts are required to mitigate this risk is not obvious. But the question of how to prevent African-American defections into Trump’s camp must be taken just as seriously as how to increase black turnout. Even a small increase in the president’s share of the black vote in Wisconsin or Pennsylvania could prove decisive for his reelection.

Similarly, Democrats need to recognize Trump’s feigned support for expanding the social safety net as an urgent problem. The responsible members of the Fourth Estate should strive to put the president’s campaign promises into the context of his governing record. But Democrats cannot count on the political press withholding unearned credulity. In the general-election campaign, the party must not cast Trump as an aberration from the conservative movement’s respectable traditions (as Hillary Clinton did for much of 2016), but rather, emphasize the myriad ways he represents an unusually “severe” strain of that ideological tendency.

Donald Trump is not an exceptionally moderate Republican president, but he plays one on TV. And in our sorry excuse for a democratic society, that might just be enough.