I didn’t really think I’d ever have a Ring doorbell. I knew that “millions of users” worldwide had installed one of the many cloud-enabled security devices sold by the company, which is owned by Amazon, and I’d seen dozens of quasi-viral Ring-camera videos, often broadcast on local television news: clips of porch pratfalls, curious animals, petty criminals, particularly skilled or incompetent delivery drivers, all providentially recorded and uploaded by the Ring’s fisheye lens to the cloud. But I’m not personally much troubled by petty crime — I’ve had a package stolen only once in the ten years I’ve lived in New York — and I couldn’t see myself getting much mileage out of a video doorbell, except to prank friends and annoy my girlfriend.

On the other hand, I am very troubled by dystopian future-tech. Over the last year I’d spent a lot of time reading about Ring — dozens of articles published in the Intercept, Recode, Vice, and Cnet — detailing the company’s sloppy security practices, secretive police partnerships, and many potential privacy violations. Ring was a prominent rationale for the tech experts who named Amazon “the most dangerous tech company” in Slate’s recent poll. This seemed like a good reason to get a Ring. Why not see for myself what it was like to live with one? Was it as useful as its popularity suggested? As dangerous as its detractors feared? So, last year, I emailed the company and asked for a test unit. A few days later I received a test unit of the Peephole Cam, a newish model with a small footprint designed for apartment-dwellers and renters.

As a camera, the Peephole Cam, like other Rings, is boringly straightforward. There’s a doorbell button on it that, when pressed, sends an alert to your phone, and it has a small speaker which can function as an intercom. You’ll also get an alert whenever the camera senses activity, allowing you to see what’s moving outside the door; by default, the camera records 30 seconds of video whenever its motion sensors are tripped. It’s also very easy to install. You unscrew your apartment-door peephole, screw in the Ring hardware, snap in the rechargeable batteries, and download the app.

It’s a bit more difficult to explain to your neighbors. Shortly after installing the camera on my apartment door last year, I ran into my upstairs neighbor outside my door and immediately felt embarrassed that I’d turned the second floor of our building into a hallway-length panopticon. My attempt to explain why his movements up and down the stairs were now being monitored was, I think, the longest sustained interaction we’d ever had. To his credit, he was gracious about it. I know this because I was able to rewatch our conversation. My doorbell had automatically recorded it and stored it in the cloud.

What does one do with such recordings? You can play them back to yourself, as I did, or share them with friends as video files. Or you can upload them to the Ring app’s “Nearby Incidents” feed — which in turn is used to populate another, standalone app developed by Ring called Neighbors. This is where Ring gets interesting.

A sort of cross between the police-scanner app Citizen and the neighborhood social network Nextdoor, Neighbors is designed to allow Ring owners to upload videos taken by their cameras — and non-Ring owners to watch them and keep tabs on what’s happening in their neighborhoods, from the point of view of others’ Ring cameras. “When communities work together, safer neighborhoods become a reality,” the website copy reads. “Connect with your neighbors and stay up-to-date with what’s going on in your neighborhood.”

If you strip away the touchy-feely marketing or rhetoric about making wholesome local connections, Neighbors is a social network for crime. I’m not sure how else to describe it. If you open Neighbors and create an account with your home address (you don’t need a Ring camera to download or use it), you’ll find a list, arranged in the familiar, reverse-chronological feed format of your social network of choice, of nearby crimes. Or, maybe not crimes, but things that appear to be crimes, or seem like they might eventually become crimes, or should be crimes, or are, in someone’s mind, crime-adjacent. Besides dry summaries of local police scanner chatter posted by the “Ring News Team” — “There are reports of a stabbing near 3rd St & 3rd Ave.” — the Neighbors feed consists mostly of videos recorded by people’s Ring cameras. In most places this means videos of package thieves and “suspicious” strangers. (“Who is this?” asks one Brooklyn neighbor, captioning a video of a man in an undershirt walking up to the door. “Should keep doors locked at all times,” observes Neighbor27.)

Until recently, Neighbors itself provided five categories for posts, so you can filter your feed according to your appetites and specific tastes as a neighborhood busybody. Those categories, from Defcon 5 to Defcon 1, are “Lost Pet,” “Safety,” “Stranger,” “Suspicious,” and, yes, finally, pure “Crime.” Starting this week, a new, less anxiety-inducing category will join those five: “Neighborly Moments,” which, according to Ring’s announcement, let you “highlight … acts of kindness and help your community celebrate them together.” Were I to share the video of myself and my neighbor, I might categorize it as a “Neighborly Moment.” What could be more neighborly than explaining the surveillance zone of our apartment building?

The introduction of Neighborly Moments seems designed to mitigate the relentless fear inculcated by the app. The problem is that the fear is the fun part. When I first downloaded neighbors, I filtered out “Lost Pet” posts almost immediately. Boring! What remained was a terrifically addictive, a wildly engaging hodgepodge of voyeurism, suspicion, unease, and mystery. Why would I dilute that with sentimental glurge? I created accounts for the Brooklyn neighborhood I live in now and the Los Angeles neighborhood I lived in ten years ago, as well as for suburbs and towns in New Jersey and the Bay Area where I’d read viral stories about Ring-captured videos. Through the fisheye lenses of Neighbors users’ Ring cameras, all of them became seamier, grittier, awash in petty crime, trespassing, danger, madness.

But as entertaining as Neighbors is, it’s haunted by a background sense that maybe you don’t really need to know quite so much about your block, or your neighborhood. Moments you’d never have been aware of without the Ring — a stranger stepping on your stoop, or knocking on your door — mount as evidence of possible danger and urban decay. Even unquestionably innocuous activity, like me unlocking my own door, is lent the frisson of danger thanks to the security-camera-style footage.

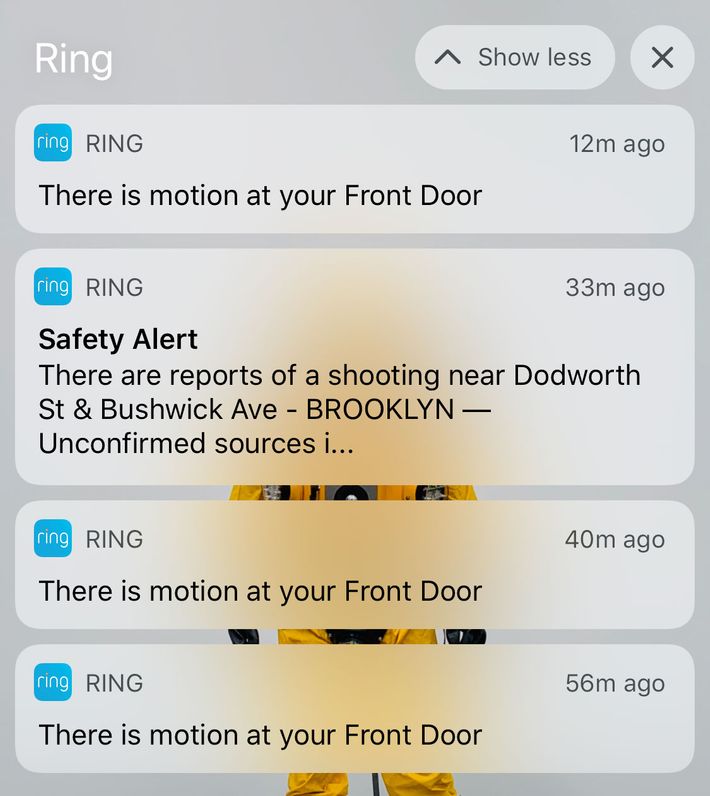

Also by default, the app notifies you of “Safety Alerts” from the “Nearby Incidents” feed. One evening not too long after installing the camera, while out for dinner with some friends, I received an notification from Ring: “There are reports of a shooting near Dodworth St & Bushwick Ave - BROOKLYN.” Twenty minutes later, my phone buzzed again with another notification: “There is motion at your Front Door.” My apartment is two miles away from the intersection where this unconfirmed shooting had reportedly taken place, on the second floor of a building with dead-bolted front door; as I said, I’ve never once felt scared or unsafe in my apartment, or even in my neighborhood in general. And yet, for a nanosecond, staring at the alerts on my phone, I was seized with panic: A shooting? In Brooklyn?? Motion? At my front door?? What was happening outside my apartment?

As it turns out: My upstairs neighbors — the ones I’d shamefully tried to explain the Ring to earlier that week — were leaving their apartment. Strolling through the hall past my door, they’d tripped the motion sensor, as I was able to tell when I opened the app and watched a clip of their departure. I could hear part of their conversation; had I wanted to, I could even have spoken to them through the speaker on the doorbell. (“Be careful, my app says there was a shooting in Bushwick!”) Whatever instinctive, immediate panic I’d felt was long dissipated. Here, phone in hand, I was in control — Brownstone Big Brother, vigilantly monitoring my empty hallway from a Japanese restaurant down the street. Sure, even a moment’s prior reflection would have indicated to me that obviously, nothing was happening outside my apartment that I needed to know about. But who needs reflection when you have an app?

You don’t need to use the app and experience its adrenaline roller coaster to understand why “Neighborly Moments” won’t transform the Ring experience. You just need to see the way Ring’s marketing strategy relies in a large part on convincing homeowners that their property is constantly threatened by crime, and that Ring cameras can help prevent it. Since 2016 Ring has partnered with police departments and local governments across the country to provide discounted or subsidized Ring doorbells, premised on the idea that Ring is an effective crime-fighting tool. In some towns, Ring and Amazon help the local cops set up package-theft sting operations with cutesy names (“Operation Grinch Grab”), videos from which are pitched — by Ring publicists — to local news channels, which happily broadcast quasi-viral video of entrapped “grinches” lifting Amazon-branded packages, helping convince people to buy Ring cameras themselves.

There’s not much hard evidence that Ring cameras actually do anything to make people, or their property, safer. (A study often touted by the company as proof of its cameras efficacy as crime-stopping tools was persuasively disputed by the MIT Technology Review in 2018.) But the inconclusive evidence about Ring’s efficacy as a crime-stopping tool hasn’t stopped police departments from continuing to partner with Ring — probably because Ring provides a special dashboard for law enforcement that lets them search by time and location for footage posted to the the feed. In towns sufficiently blanketed, Ring cameras essentially create a comprehensive, readymade surveillance network for local police. Of course, Ring doesn’t provide law enforcement with videos without a subpoena, so police must request clips from the camera owners themselves. But what law-abiding homeowner would refuse? (In the past, some police departments have required that people who receive Ring cameras through giveaways hand over any requested video to police. Ring told CNET that it “doesn’t support this model” and “was reaching out to police partners to make sure this wasn’t a requirement for Ring giveaways.”)

It’s not hard to extrapolate out the dystopian future augured by Ring-blanketed suburbs. Last summer Amazon patented what it called a “surveillance as a service” system: Essentially, a way to take its in-development air force of delivery drones, and turn it into an automated neighborhood watch, swinging by subscribers’ homes to watch for, say, “a broken window, a detection of graffiti, or a fire.” Such footage would no doubt be of great interest to police — not to mention the many users of Neighbors anxious for the next peek into their neighbors’ backyards. If that’s not dark enough, the Intercept recently reported that Ring had been planning a feature that would allow users to create and share “neighborhood watch” lists of unwanted persons, powered by Amazon’s facial-recognition technology. If I share with you my list of blocked faces, does that qualify as a “neighborly moment”?