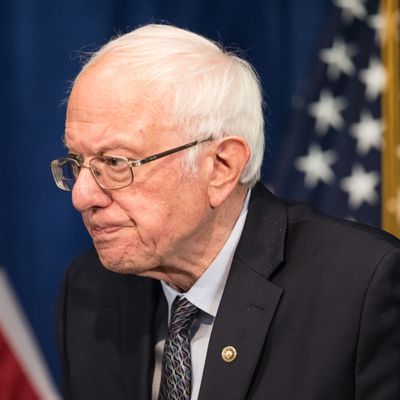

After his shocking, sudden defeat on Super Tuesday, it made sense that Bernie Sanders would stay in the race and try to regroup, perhaps regaining momentum with a surprise victory in Michigan, like the one that had revived his campaign four years before. After he lost every county in Michigan, it made sense he would stay in the race and force Joe Biden to debate him one on one, possibly triggering a meltdown and forcing Biden supporters to reconsider his electability. After Biden turned in a strong debate performance (perhaps his strongest), it even made sense for Sanders to stick around a few more days and see if lightning struck.

Now Sanders has lost once again. His aides had expressed hope that one of tonight’s states, Illinois, might somehow deliver a small victory. Instead Biden won it in another blowout. Sanders had pinned some hopes on the belief that reminding Democrats of Biden’s history of considering Social Security cuts as part of a deal to reduce the deficit might bring him down, and used those clips in ads. Florida Democrats said they trusted Biden over Sanders to protect Social Security.

Even before tonight, FiveThirtyEight gave Sanders a 0.1 percent chance of denying Biden a majority of delegates. He now needs to win the remaining states by massive, blowout margins — vastly larger than his 7 percent margin of victory in California, which is demographically one of his best states, and where he also benefited from a divided field of opponents who have since dropped out.

As Nate Cohn points out, every Sanders win so far — in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, California, Colorado, Utah, North Dakota, and Vermont — has added up to a net 108-delegate margin. Biden will net almost as many delegates in Florida alone.

The mere act of having to schedule elections has become a significant administrative burden for states, which have to scramble to set up remote-voting options for fear that polling places will spread the coronavirus. Several states have already delayed their primaries, which will in turn elongate the process. Pushing contests back into June will force Biden to take weeks or months longer to clinch his delegate majority.

There is no reason, save an unforeseeable tragedy, that would cause voters to suddenly change their minds at this point. It is not like Jimmy Carter in 1976 or Bill Clinton in 1992 or Barack Obama in 2008, when voters were swept off their feet by a new figure on the scene. Sanders and Biden are both very well-known brands. Biden has survived thorough vetting.

Sanders has, of course, built a passionate movement associated with well-defined ideas. It’s not clear what he has to gain by devoting that movement and its resources to the cause of losing a long series of primaries. Deepening the association of Bernie-ism with a failure to accept political reality and disinterest in the Democratic Party’s greater good seems counterproductive to its long-term goals.

What possible reason does he have to continue?