Tuesday night’s election results appear to have wrapped up the Democratic nomination for Joe Biden much faster than seemed possible even just a few weeks ago. But if before Super Tuesday we weren’t at all sure who would be the Democratic nominee, we thought we had a pretty good idea of what their campaign would look like — it would look like every other presidential campaign in memory, full of rallies and rope-line greeting, and debate halls full of voters. Thanks to the coronavirus, it’s beginning to look more likely that we’ll be at least launching the general election — and conceivably even completing it — without any of that, a 21st-century pandemic giving us, potentially, the first post-hustings presidential election.

The possibility dawned on the campaigns somewhat slowly. As Bernie Sanders got ready to speak at the St. Paul, Minnesota, convention center the night before Super Tuesday, congresswoman Ilhan Omar looked out at the tightly packed crowd and asked the 6,000 Democrats to hold hands. The nervous laughter that usually greets that kind of request dribbled out at first, swiftly followed by an uncomfortable, mumbled hush. Concern about the coronavirus wasn’t yet at deadbolt-your-doors-and-seal-your-windows levels. But it was acute enough that Sanders’s press corps — now looking up, eyes wide and disbelieving — had already nicknamed the senator’s recent campaign swing the #coronatour, and some news outlets had begun restricting their reporters’ travel.

Then, a moment later, everyone dropped their neighbor’s hands and moved on. They were just another crowd of thousands huddled for hours indoors (strike one) amid the emerging pandemic, gathering to hear yet another septuagenarian man with underlying health issues who’s spending all his time in transit (strike two). They were, whether they knew it or not, just another set of participants in an eerie, weeks-long pattern repeating itself at Sanders and Joe Biden events as the campaigns made their COVID-19 responses up as they went along, assuring the journalists trailing them that they wouldn’t sleepwalk into disaster even as the public woke up to the threat, then started to panic.

The night before Sanders spoke in Minnesota, more than a few N95 masks dotted his crowd of over 15,000 in Los Angeles. The following one, when a burly Sanders supporter in Essex Junction, Vermont, joked to me while washing his hands that he had just left quarantine, no one in earshot laughed, and everyone in line for the sink kept their distance. Crowds didn’t thin, but within days, hand soap started appearing at rallies, first in the press pens and then at the doors.

And the campaigns rolled on, frantic for votes and for approval even as the world around them shook. They insisted to anyone who would listen that they were in constant contact with local health officials everywhere they went — ready but desperately hesitant to make any drastic decisions that would take them off the trail. The AFL-CIO canceled its Orlando forum for the Democrats, and the Washington Democratic Party axed its big weekend fundraiser. Biden, eventually, agreed to cut back on his beloved intimate rope-line sessions with his fans, and Sanders’s braintrust decided against a Seattle-area rally the weekend before Washington State’s primary, an adviser told me, avoiding a hotspot for the disease.

And still the headlines grew grimmer as the willful ignorance of the third candidate in the race, Donald Trump, grew more glaring.

On Saturday night, around the time three new cases were identified in the D.C. area, Trump said he’d continue to hold his “tremendous rallies.” A reporter asked if the president, sitting for dinner at Mar-a-Lago with Brazil’s right-wing leader, Jair Bolsonaro, was concerned that the virus was getting closer to the capital. (One of Bolsonaro’s aides, also on the trip, would soon test positive.) “No, I’m not concerned at all,” Trump insisted. “No, we’ve done a great job.” Two nights later, as Trump refused to tell journalists in D.C. whether he’d been tested yet, Biden rallygoers in Detroit were greeted by peppy volunteers offering pumps of hand sanitizer as they entered. That afternoon, Sanders held a roundtable with medical professionals at the Detroit airport Westin. Addressing a room stacked with Purell dispensers, Sanders criticized the administration for ignoring science, reiterated his calls for Medicare for All and paid sick leave, and insisted anyone should be able to get tested, regardless of their socioeconomic or immigration status.

Still, when a reporter asked Sanders about the precautions he himself was taking, he brushed the question off: “I am running for president of the United States,” he said, “and that requires a whole lot of work.” Sanders had headlined two rallies in Michigan the day before, and had another scheduled for Cleveland the next day, too. At least a dozen reporters were still following him everywhere — to North and South Carolina, Massachusetts, Virginia, California, Utah, Minnesota, Vermont, Arizona, Illinois, and Michigan in the preceding days alone — and at least 3,000 voters were greeting him at every stop. Clearly fed up with the line of questioning that night, on CNN, he offered Chris Cuomo a drop of reassurance: “I have used more hand sanitizer in the last two weeks than I’ve used in my entire life.”

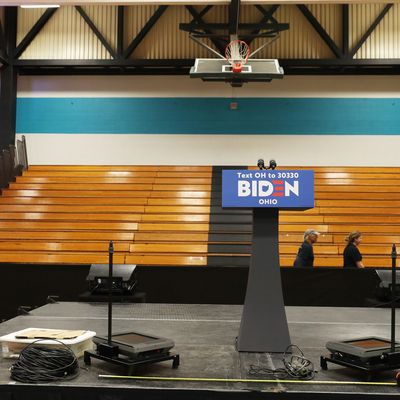

The next afternoon, Sanders canceled his evening speech. “We are heeding the public warnings from Ohio state officials, who have communicated concern about holding large, indoor events during the coronavirus outbreak,” his communications director said in a written statement, shortly before the candidate flew back home to Burlington, offering no public comment of his own. “All future Bernie 2020 events will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.”

That morning, a video of Biden had gone viral. In the clip, he confronted a Detroit Fiat Chrysler factory worker who accused the candidate of trying to take away his guns. The setting was at least as jarring as the back-and-forth: Biden was standing in a sea of laborers, just inches away from them on all sides. Meanwhile he, too, was scheduled for an evening event in Ohio. But 32 minutes after Sanders’s announcement, Biden canceled his too, and soon after also scrapped his planned Thursday event in Tampa. Network cameras captured him arriving in Cleveland, then re-boarding his campaign charter jet a few minutes later. He was heading back to Philadelphia, where his campaign is headquartered, and where no crowd was waiting. Soon after Biden boarded, a pair of announcements landed in reporters’ inboxes just about simultaneously. The DNC and CNN had one warning: Sunday night’s debate in Phoenix would now be held without a live audience, a press filing center, or a spin room, “at the request of both campaigns and out of an abundance of caution.”

The Trump campaign, perhaps unsurprisingly, had a very different idea: The president would be headlining his next rally, in downtown Milwaukee, the following Thursday. Which suggests, of course, another possibility for the summer and possibly fall, if the outbreak should continue or even reemerge then, as scientists suggest it might: With the Democratic nominee campaigning primarily virtually, the president could continue to run an incautious, (relatively) traditional out-and-about race, in part to signal normalcy to voters and consumers, but more realistically out of resentment for the advice of experts — in part to support the perception in some quarters of the right that the outbreak is a liberal plot designed to take him down, and in part because, being who he is, he loves nothing more than a rally and all those people chanting his name. However many might be infected, or even die, as a result.

Or not. Slightly over 24 hours later, Trump canceled his rally in Wisconsin. The Democratic debate was moved to Washington, D.C., and Jorge Ramos, one of the anchors, was pulled from the broadcast because of possible exposure. Biden and Sanders both instructed their staffs around the country to work from home, and canceled the rest of their upcoming in-person events. In a week, the general election has entered totally uncharted territory.