In the increasingly deep shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Democratic presidential nominating process is limping along, with Joe Biden slowly but steadily building on a delegate lead over Bernie Sanders with a lot of Biden-friendly primaries still ahead. He should rack up three more wins on March 17, with a particularly rich delegate haul in Florida and Illinois and more modest gains in Arizona.

But with five states (Louisiana, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland and Ohio) having already delayed primaries that Biden was expected to win, and more postponements likely in the near future, the former veep’s conquest of the nomination has been put into slow motion. This presents Team Sanders with something of a dilemma. Politically speaking he’s like a condemned man benefiting from serial stays of execution.

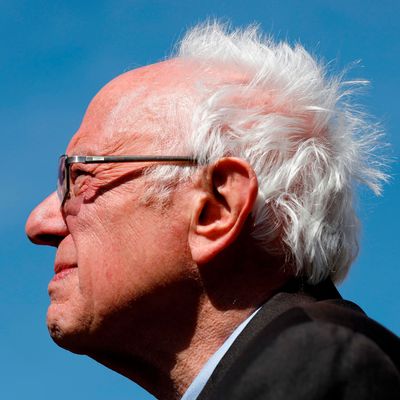

According to Politico, Sanders is not inclined to take a hint and fold his campaign:

Bernie Sanders’ path to the Democratic nomination is closing, but a quick exit is far from guaranteed — even if he gets wiped out Tuesday.

From his debate posture to staffing moves to the “virtual rally” he convened Monday evening, the Vermont senator is signaling that he may not be ready to concede.

His is not, you see, just any old presidential campaign:

If Sanders remains in the race, it will be in part to keep his “political revolution” alive. According to people familiar with his thinking, Sanders will not only consider what’s best for his campaign, but also the progressive movement.

Many of Sanders’ aides and allies also expect him to press onward after Tuesday. They see a benefit in amassing as many delegates as possible in order to influence the party platform at the Democratic National Convention this summer — even if Sanders himself can’t win the nomination.

“Movement” candidacies end slowly because the movement itself is eternal. And Sanders has two rationales for continuing his latest, and perhaps his last, campaign. First, Biden won’t formally win a majority of pledged delegates for some time, and in a year like this one, who knows what could happen down the twisting, pandemic-infected road ahead? And second, there is the fool’s gold of party-platform planks to covet and perhaps shape.

But if Sanders goes O-for-three as expected on March 17, he will have lost 19 of the last 24 state primaries. And despite all the distractions of the coronavirus crisis, Democrats who view themselves as members of a party rather than a movement will become increasingly restive about a “revolution” that seems inclined to fight on to the bitter end, feeding Trump’s reelection prospects:

If Sanders continues his bid after Tuesday, he will face an onslaught of pressure from establishment Democrats and even some progressives to drop out. Many are wary of a long, divisive primary after 2016, and eager to take on President Donald Trump with the benefit of a united party. Jim Clyburn, whose endorsement helped fuel Biden’s comeback victory in South Carolina, said on the day of the March 10 primaries that the Democratic National Committee should “shut this primary down” and cancel debates if the former vice president swept the races, which he went on to do.

Part of the psychology of the Sanders campaign may be affected by his apparent conviction — reflected in his line of argument during the March 15 debate — that the fallout from the coronavirus provides one giant talking point for his pre-pandemic agenda, from Medicare for All to free college to a general redistribution of wealth. As my colleague Eric Levitz pointed out, Sanders’s version of democratic socialism may soon seem entirely proportionate the social and economic disaster facing this country in the very immediate future, as even Biden’s prescriptions are beginning to indicate:

Biden’s answers about how he would combat the coronavirus as president was (in contrast with Sanders) short on moral critiques of underlying systems and structures of power, and long on bullet-pointed lists of immediate public health and economic measures for mitigating the coming damage.

And yet, the “results” that Biden promised were themselves unimaginable in the absence of nigh-revolutionary changes to America’s political economy.

That reality — that politicians from Joe Biden to Mitt Romney to Trump himself are now embracing “revolutionary” responses to COVID-19 and its consequences — must be frustrating to Sanders and his core supporters, and probably explains his debate focus on reminding people of Biden’s past ideological sins. That it seems “divisive” to unity-obsessed Democrats is understandable and at the same time beside the point. The coronavirus is pushing Biden and the Democratic Party to the left; the Sanders campaign is just trying to accelerate the process and vindicate its long march toward ideological victory. But at the same time, it must feel somewhat superseded by the furies released by the pandemic.

So does Sanders stay or go, and if he goes, when’s the right time? Team Biden will undoubtedly probe for the kind of gestures or concessions that might tempt Sanders to claim moral victory and go home, whether it’s a “progressive” running mate or some more coronavirus-rationalized policy shifts. Democrats might as well be patient with Sanders and his people; it’s not like the voting public is going to care that much whether Biden officially wins the nomination next week or at some point later in this season of fear and courage.