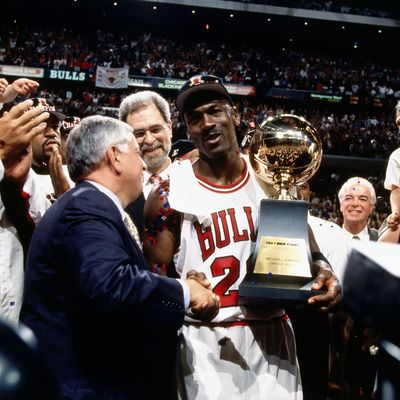

After weeks of airing painful HORSE competitions, extensive investigations of Tom Brady’s Instagram, and countless “debate” shows conducted over Zoom, ESPN is finally going to give us some quarantine content we actually want to watch. The Last Dance, the long-awaited ten-part documentary about the final season of Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls dynasty, debuts Sunday night at 9 p.m., airing two episodes every week through May 17. The series reportedly features never-before-seen footage of that traveling road show of a team, as well as exclusive interviews with Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Barack Obama, and hundreds of others. The Last Dance was initially supposed to premiere in June, likely tied to the NBA Finals. But with sports on an extended hold, and fans already salivating over the film, ESPN smartly moved it up. I’ve put the airing of every installment in my calendar for the next month; it’s not like there’s anything else in there.

The Last Dance promises to be the biggest documentary event for ESPN since 2016’s Oscar-winning O.J.: Made in America, and all told, it’ll probably end up being even more massive. It’s also considered the next step for the network’s ongoing and well-respected 30 for 30 series, which won ESPN that lone Oscar, and has featured films by directors as varied as Barry Levinson, Albert Maysles, Ron Shelton, Ice Cube, Errol Morris, Barbara Kopple, Ryan Fleck, and the late John Singleton. It is worth noting — and almost never pointed out — that The Last Dance is not part of the series at all. It is actually a co-production between ESPN Films and Netflix (it will debut internationally on Netflix April 20). But it’s a mark of the brand’s influence that even though The Last Dance is not a 30 for 30, we instinctively refer to it as one.

30 for 30 began back in 2009, the brainchild of producer Connor Schell (now executive-vice-president of ESPN) and then-ESPN superstar sportswriter Bill Simmons, who was eager to spread his tentacles throughout Bristol. It was pitched as a way to celebrate ESPN’s 30th birthday in 2009: 30 films about smaller sports stories from the past that had been forgotten about, or at least not covered in the obsessive way sports were being covered in the new century. Simmons told me back then that ESPN wanted to take back the sports documentary from HBO, using “the indie film model”: finding established filmmakers to go deep on topics they were personally interested in. (Ironically, Simmons ended up producing the documentary André the Giant for HBO after his unceremonious exit from ESPN.) This approach led to terrific, very-un-ESPN films like Brett Morgen’s experimental June 17, 1994 (which told the story of that wild sports day with no narration or interviews), Mike Tollin’s fantastic Small Potatoes: Who Killed the USFL? (which featured an infamous interview with Donald Trump), and Hoop Dreams’ Steve James’s No Crossover: The Trial of Allen Iverson. The movies were searing and opinionated and often angry; they were sharp-elbowed and risky in a way ESPN had long forgotten how to be.

30 for 30 was an immediate, massive hit for ESPN. The network promoted Schell, gave Simmons his Grantland website, and made a ton more of the documentaries, despite no longer celebrating its 30th anniversary. And 30 for 30 continued to churn out excellent films, my favorite being Benji, about late Chicago high-school-hoops legend Ben Wilson. But one couldn’t help but notice a certain sameness creeping in, a formula that consistently worked, but which was a formula nevertheless. Mavericks like Kopple and Maysles went back to their independent films, replaced by young filmmakers within the 30 for 30 system, like The Last Dance director Jason Hehir and Ezra Edelman, who had directed the 30 for 30 film Requiem for the Big East before helming O.J.: Made in America. The films still worked, but no longer was there the unpredictability of a Brett Morgen or an Alex Gibney.

30 for 30 now produces podcasts, including an outstanding one last year about Donald Sterling, The Sterling Affairs, as well as films made in conjunction with NASCAR, the NBA, and Major League Baseball. ESPN says it has many more 30 for 30 films coming later this year, though it isn’t naming them; its most recent one, Vick, about Michael Vick’s dog-fighting trial and conviction and the aftermath, aired in late January. It was good, but it didn’t feel dramatically different than the rest of them.

The question is whether The Last Dance signals a change for the 30 for 30 format, or a larger change for ESPN itself. One of the reasons everyone is assuming the film is a 30 for 30 is because it looks like one; it features big moments from sports history, interviews with the major players, smart talking heads putting everything in perspective, top-shelf production values. (The format is actually considerably different than O.J.: Made in America’s, but the length is sure similar.) Is the fact that it’s not under the 30 for 30 banner a shift away from the franchise and more toward deals like the one with Netflix? And hey, why does ESPN need Netflix to help make its big event movies anyway?

Whichever direction the network goes, 30 for 30 has accomplished what Schell and Simmons set out to do — and much more. In many ways, the series has transcended itself. It has been such a success in the popular imagination that the name has become shorthand for “sports documentary.” (I have heard several commentators note that they are already eagerly anticipating the episode about our current world without any sports.) Someday they’ll make a documentary about 30 for 30. They’ll surely just call it a 30 for 30.