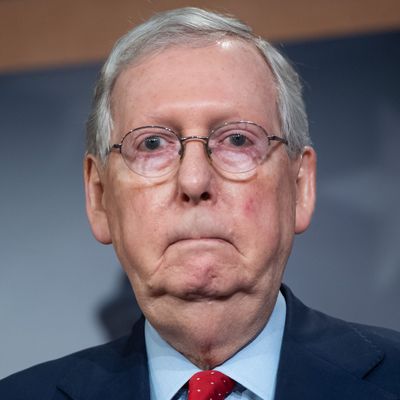

In an interview with conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt on Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell dismissed calls for federal aid to states, saying states’ financial troubles are closely related to reckless decisions about public employee pension benefits and other matters, and that if states need relief from promises they’ve made but can’t keep, they should be allowed to go bankrupt instead of coming to the federal government for a bailout.

There are two problems with this idea. One, which I’ll get to in a moment, is that permitting states to declare bankruptcy would cause a variety of problems in financial markets, hurting the economy and raising the cost for even financially healthy states to borrow. But the other is that, even if we did allow states to declare bankruptcy, it wouldn’t be an applicable tool for the fiscal crisis state governments are just starting to find themselves in. Bankruptcy is for insolvent entities. And while states’ finances will be gravely impaired by the drops in tax revenue we are about to experience, it is unlikely any of them will be made insolvent by it. States’ ability to tax is a very powerful thing, and states will be able to pay their debts even if the federal government provides them no additional aid. The problem is what steps states will have to take to pay those debts, and what negative economic and social effects those steps will cause.

One reason that governments borrow money cheaply is that they have a wide variety of tools available to them that individuals and corporations do not. When Delta’s customers disappear during a crisis, it can’t force them to keep paying for airline tickets. But states have the power to tax, and to increase taxes in times of budget shortfall. There are consequences to that choice — residents may respond to tax increases by working less, or by hiding income, or even by moving away. But those choices are a lot harder for people to make than the choice to stop flying (or even to fly another airline). People own real estate. They have jobs and links to family and communities. Their location is pretty sticky. And that gives states a lot of flexibility to lay their hands on more revenue when they need to. States also have a lot more flexibility to cut spending than corporations do. If a corporation spends less on the products and services it provides, that will likely cut seriously into the revenue it can collect. But states can hold taxpayers captive for service cuts much like they can do for tax increases. So that provides a clear non-bankruptcy roadmap for states to deal with a situation where their debt and pension obligations remain substantial and the economy has fallen apart: They can raise taxes and cut spending.

The problem with the approach I am describing is that it is miserable. At a time when households are already immiserated by crisis and many businesses are closed, we would ask them to pay more in taxes and receive less in government services. These moves would also exacerbate the negative economic effects of the coronavirus crisis itself: If we lay off teachers in large numbers, cut police officers’ pay, strip benefits from low-income people, reduce payment rates to Medicaid providers, raise income and sales taxes — all those changes leave people with even less money to spend, forcing them to cut back further on the products and services they buy, and reducing income and consumption throughout the economy. And those negative knock-on effects would further reduce state income and sales tax receipts, necessitating even more spending cuts and tax increases, and so on. This is the reason states need a bailout: not because they would otherwise be unable to pay their debts, but because the things they would otherwise do to pay their debts would wreck the economy.

The “Blue State Bailout” frame some Republicans are using to discuss the idea of state aid is ridiculous. The idea that only states like New York and Illinois will need federal assistance to avoid tremendous cuts to their budgets is a fantasy. The negative economic effects of this crisis are national. Since the crisis seems to be reducing household consumption even more rapidly than household income, at least in its initial phase, it’s likely some of the hardest budget hits will be in Republican-run states like Florida and Texas that don’t have income taxes and rely heavily on sales tax. These two states are also unusually dependent on tax revenue from sectors (tourism and energy, respectively) that have been devastated by the crisis. That some blue states like Illinois and New Jersey (and some red ones like Kentucky) have made irresponsible, unfunded pension promises is beside the point. Pensions are not driving this state fiscal crisis. The current crisis is due to is the huge reduction in current economic activity that is hitting all states, whether their prior fiscal policies were prudent or not.

So, what would happen if we gave states a theoretical power to declare bankruptcy, one that wouldn’t even make sense to exercise in this crisis? What would happen is new uncertainty would be injected into the market for municipal debt. Holders of states’ bonds would have a new thing to worry about: Am I extending credit to an entity that might declare bankruptcy? If investors take that possibility seriously, they will demand higher yields. You could argue that this is useful price discovery: Spreads in state bond yields would tell us which states investors think are being responsible, and push the irresponsible states toward better policy choices. But if you look around at what has happened in bond markets over the last few months, you would realize this argument is wrong. The Federal Reserve is already having to intervene throughout the credit markets to soothe risk fears and ensure the continued availability of credit, because otherwise borrowing costs are spiking even for creditworthy, responsible borrowers. Added panic in the markets isn’t helping to allocate capital, it’s just making it harder for everyone to borrow.

All a state bankruptcy option would do is make the Fed’s job of smoothing out the debt markets even harder. It wouldn’t give the states a tool that would help at all with the issue they face today. And it wouldn’t provide any relief to state residents — which is to say, Americans — who face severe economic and social disruptions if their states are forced to weather this crisis on their own.