Another 1.5 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits last week — and another 23,000 new U.S. cases of coronavirus surfaced on Wednesday. Like the interminable Zoom meetings they’ve forced white-collar workers to endure, the recession and pandemic aren’t going to wrap up the minute we decide we can’t take them anymore.

Earlier this month, a surprisingly (and misleadingly) strong May jobs report — combined with a bafflingly robust stock market recovery — fortified the congressional GOP’s inveterate complacency about mass economic suffering. Republicans opted to leave for summer recess without extending enhanced unemployment benefits, approving further stimulus checks, or sending a single dollar of unconditional fiscal aid to America’s cash-strapped states and cities. Instead, Mitch McConnell plans to resume negotiations over a hypothetical fourth coronavirus relief bill in late July. Officially, the GOP’s rationale is that we will have a better sense of how much support the economy truly needs in a few weeks, after the curative benefits of reopening have taken effect. But it also seems likely that Republicans hope to milk some leverage out of negotiating on a cliff’s edge: If no bill passes by July 31, America’s unemployed will see their weekly income slashed by $600. Faced with the looming threat of mass immiseration, perhaps Democrats can be goaded into immunizing negligent business owners against liability lawsuits.

Whatever the GOP’s rationale for withholding relief, their stance is an expression of ideological madness.

Republicans have put needless constraints on stimulus during this recession. But unlike in 2009, the party has affirmed the basic premise of countercyclical fiscal policy: When the private sector is unwilling or unable to provide workers with income and the economy with investment, the public sector should replace that demand with deficit spending, so as to prevent the downturn from feeding on itself. Altogether, Congress has authorized more than $3 trillion in relief funds. And according to the Trump administration’s own data, that big government spending has worked like a charm: Even as the economy hemorrhaged jobs in April, personal income in the U.S. rose by a record-high 10.5 percent — thanks entirely to government transfers.

And yet, while the federal government has massively increased its spending during the coronavirus recession, just about every state and city is moving in the opposite direction.

This is because, unlike Uncle Sam, state governments can neither print their own currencies nor borrow money at near-zero interest rates. And many are also constitutionally obligated to maintain balanced budgets. For these reasons, when a pandemic increases a state’s public health and social welfare liabilities — while decimating its sales and income tax revenues — it has little choice but to actively worsen its own recession by slashing public employment, services, and investment.

More precisely, this is the only choice that states will have if Congress denies them access to the U.S. government’s copious fiscal capacity. And if Congress understands that it is bad for the public sector to slash social support and public employment in the middle of a pandemic-induced recession — as its past three months of legislating suggests — then it has no rational basis for denying states such access. There is no theory of recession-fighting that prescribes deficit spending at one level of government, but draconian austerity at all lower levels. No coherent model of the economy could ever justify such a policy. And yet, for three months now, this is the policy that we have pursued.

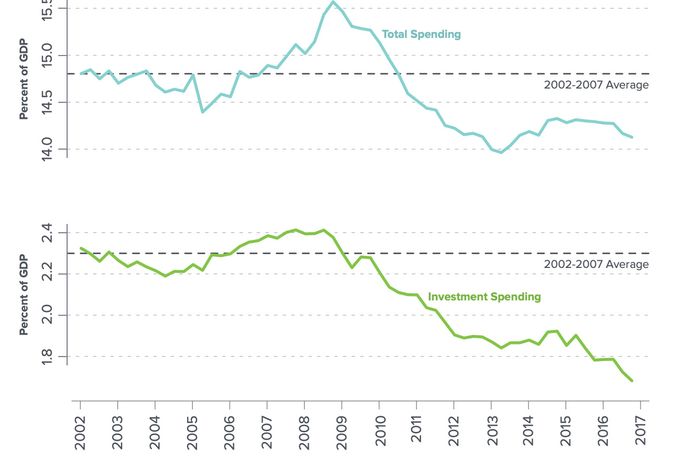

And there’s reason to fear that it is a policy we’ll pursue indefinitely. After all, this is precisely what we did during the Great Recession. One of the primary reasons why the post-2008 recovery was so slow and weak was that states and cities were laying off workers and canceling investment projects for the bulk of it. As the Roosevelt Institute’s Mike Konczal and J.W. Mason have illustrated:

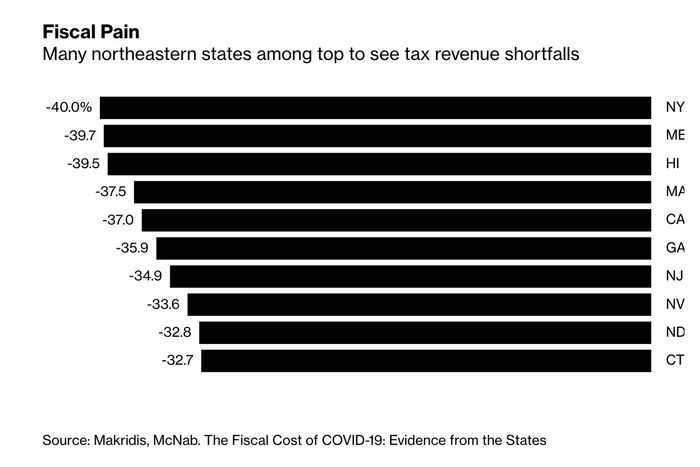

State spending remained far below its pre-2008 level through the peak of the ensuing expansion. And the coronavirus pandemic is dealing a bigger blow to stave revenues than the financial crisis ever did. According to one projection from economists at MIT and Old Dominion University, state-level tax revenues are set to decline by an average of 20 percent, with at least ten states seeing greater than 30 percent declines. The U.S. Conference of Mayors has set up a “fiscal pain tracker” that aggregates the bad news pouring out from cities across the country, as each new day brings more furloughs, layoffs, and impending cuts to basic services.

What makes Congress’s inaction all the more remarkable is that fiscal aid to states isn’t just integral to addressing one wrenching social crisis but two: It is not possible to mount a remotely credible response to the recent uprisings over police violence and discrimination while forcing cities to slash spending on health care, job training, education, housing, and social services. The Black Lives Matter movement’s demand to “defund the police” is not a call for targeted austerity, but for shifting investment away from punishment and into care and community-based violence prevention initiatives. If major U.S. cities end up slashing overall spending by upwards of 30 percent, there is every reason to expect tensions between increasingly underserved communities and overextended police departments to rise further still.

Some have hoped that if Congress didn’t relieve the fiscal pressure on states, the Federal Reserve would. But while the central bank has taken steps to ensure that states and cities can find buyers for their debt, its “Municipal Liquidity Facility” is designed solely as a lender of last resort. Rather than providing municipal governments with cheap credit on easy terms — say, a “loan” with a zero percent interest rate and 200-year maturity — it is offering them loans on less favorable terms than they can find on the private market.

Republicans have signaled that they will likely approve a modicum of fiscal aid at the end of July. But Mitch McConnell has said that the price tag on the next relief package — which, God willing, will include extended unemployment insurance benefits and aid to small businesses, among other things — cannot exceed $1 trillion. In mid-April, Republican chair of the National Governors Association Larry Hogan warned that states needed at least $500 billion in federal aid to avert “significant reductions to critically important services.” In the two months since, the fiscal outlook for states has only worsened.

Anyone who would like the United States to make meaningful progress on racial justice — or at least, avoid a depression — must call on Congress to cease needlessly starving state governments of funding. If enough pressure is brought to bear on McConnell & Co., it is conceivable that they can be persuaded to prioritize their own electoral self-interest over their ideological affinity for afflicting the afflicted.