After 111 days, Governor Andrew Cuomo is holding the last of his daily coronavirus press conferences. Cuomo claims that 59 million people were tuning into the briefings, but amid the PowerPoint slides and the daughter jokes, one question has plagued me: Whose head am I looking at? While the governor has given the briefings at various places around the state, most have occurred in Albany and were attended by the same group of capital reporters. For more than four months, I’ve been watching these reporters ask the governor questions about the pandemic while wondering: Who’s that in the first seat typing wildly? Who’s the guy with the notes on the floor? Do they all have to wear masks? Extensive reporting on the reporting has revealed the answers. And yes, there is a best seat.

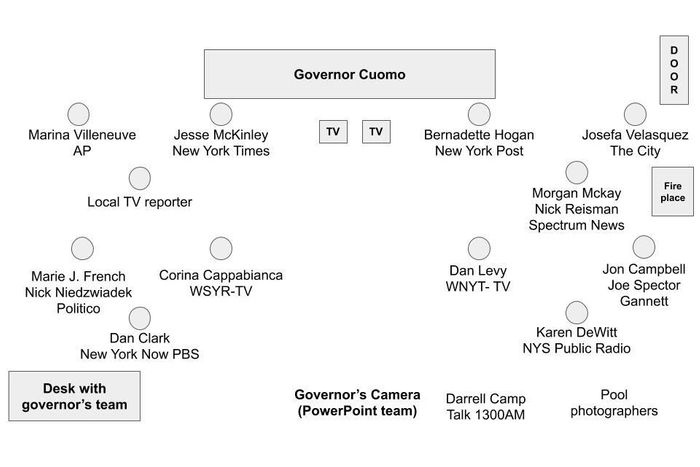

Who are these people? Here is a sketch of the usual seating chart in Albany.

In addition to reporters and the governor, the people in the room have been those Cuomo brings to the dais (usually Dr. Jim Malatras, president of SUNY Empire State College; Dr. Howard Zucker, state health commissioner; Melissa DeRosa, secretary to the governor, and Robert Mujica, director of the budget), and five or six staffers who run the audio and video of the streamed presentation. The majority of the reporters are members of the Legislative Correspondents Association, an Albany professional organization of about 40 media people. The only reporters who aren’t LCA members are Dan Levy from WNYT (usually in the third row) and Anne McCloy from WRGB (usually second row). “We’ve become part of the furniture,” says Josefa Velasquez of The City. Rich Azzopardi, senior advisor to the governor, adds, “This is a press corps that is younger, more diverse, and more gender balanced than any one I’ve seen. And I do believe that informs their questions in a positive way, with a varying degree of perspectives. I think it’s a great thing, and it’s reflected in the discourse.”

During his second-to-last press conference on June 18, Cuomo took a few minutes to praise the work done by the reporters. “Their coverage of this situation will be a course in journalism class one day I believe,” he said. “The questions, the dialogue, was as informative to people as my briefing. I actually think the back-and-forth with the press was in some ways more communicative for people.” He even acknowledged the grind, adding, “I know it couldn’t have been easy for you, because it was hell for me, and we all lived it together.”

Where have they been held? The Albany press briefings have taken place in the Capitol building’s Red Room, the governor’s ceremonial office on the second floor. Reporters use that name for the event itself, too, as in “the Red Room starts at 11:30.” “There’s three doors,” says Azzopardi. “There’s the door that lets the press in, there’s a hidden door that’s kind of carved in the wainscoting that goes into my office, and the third door is the governor’s,” connected to his office. “It’s also freezing in there,” says Velasquez. “We call it Cuomo Cold. Every time we go somewhere with him, it’s freezing.”

Any reason it’s been at 11:30 am? “It’s what it evolved into. I see people on Twitter call it Cuomo o’clock,” says Azzopardi. “It does give a little bit of consistency in a time when everything is changing and yet there is nothing to do.” In other words, not really.

What was each morning like? Doors opened to reporters about 20 minutes ahead of time, and many turned the wait into a time for socializing. “For a lot of us, this is the only interaction we get during the day,” says Velasquez. “We do realize how ridiculous this entire situation is and we’ll have this shared experience when this is all done.” Bernadette Hogan of the New York Post even started doing dramatic readings of the paper’s horoscopes. “I think it’s really funny,” said Hogan. “The other day I was like, Karen [DeWitt] you’re such a Taurus—this is so you. This is your day.”

Were there assigned seats? Not officially, but there has been an understood code among the reporters. “Some people are really territorial about their seats,” says Dan Clark of WMHT public TV. “The ethical code is ‘if your seat is stolen, and you feel you have a right to that seat, every reporter here knows they are more than welcome to speak up.’” But Clark says the governor has come to know the reporters who have been at every briefing and calls on them.

“The Albany press corps is great, and unlike a lot of state houses, it’s pretty robust,” says Jesse McKinley of the New York Times. “We all know each other very well and respect each other. We’re certainly competitors, but we’re friendly. We share tape if we miss things. We’re always willing to help each other out. It’s not like anyone’s attacking each other to get seats. In part because this has been such a day-after-day experience, people have kind of settled into their spots. I got up front fairly early because I wanted to be able to get the governor’s attention. It’s also good because I’m short-sighted—that’s something I learned in school.”

Best seat? “I think it’s the one directly in front of Robert Mujica that Josefa sits in,” says Azzopardi. “There was one day when some else was sitting there, and the room didn’t feel right.” But the reporters see it differently. “The best seats are where Jesse and Bernadette sit,” says Clark, “because in that room it’s really hard to get the governor’s attention, and to be literally six feet away from him has an advantage.” McKinley seems to agree. “I like my seat,” he says. “It’s up close. The governor is a very intense speaker a lot of times, particularly on this issue. He does make eye contact with people. You can get a sense of his mood and his intensity and more importantly his intention.” Also, he admits, “I get to lay all those papers on the floor, because my memory is so shoddy.”

Worst seat? “All the way in the back closest to the cameras—I don’t think it’s the worst seat, but it’s the last one to get filled,” says Azzopardi. “It just depends on a reporter’s voice,” says Hogan. “You’ve got Joe Spector from Gannett, who has a booming voice and I’m like, ‘Wow, I can’t even compete.’ As long as you can get your questions asked.”

What happened after the cameras shut off? “I come out of my hole. I take whatever follow-ups they have,” says Azzopardi. Then two emails go out to reporters. One is a set of numbers that the governor’s office tracks every day: number of cases, number of tests, number of hospitalizations, number of people in the ICU. The other is a PDF of the governor’s PowerPoint presentation.

Who made the PowerPoint slides? “The PowerPoint is nobody’s full-time job,” says Azzopardi. “But we do have a team of people who help put those together.” Malatras and deputy commissioner of the Department of Financial Services Gareth Rhodes also help, but the slides, Azzopardi insists, ultimately come from the governor. He doesn’t do a dress rehearsal or dry run before the presentation, says Azzopardi. “That’s not who he is.”

What safety measures have been taken? Early on, the chairs were separated. “People were understandably scared, I was scared,” says Azzopardi. He worked with the LCA on what safety measures were appropriate and together they decided that the chair move was the best option. They took a third of the chairs out of the room and Azzopardi kicked out all non-essential staff. After that, they set up photography zones. “People were complaining because there were photographers who were moving around the room and it was just an uncomfortable thing,” says Azzopardi. He worked with the photographers to put in three squares on the floor as dedicated photography spaces. “I worked with them to make sure they got the shots. There’s only so many shots you can take of someone at a table.”

Next came the mask order. “The mask rule in the room is, everyone socially distance. Wear the mask if you’re comfortable, but it’s up to you because you are socially distanced in the room,” says Azzopardi. Masks and hand sanitizer are also provided to the reporters. All the governor’s staff is required to wear a mask as well as the photographers. “Anyone who has to move around the room has to wear a mask,” says Azzopardi. “But I’ve gotten no push back to that.” The last measures were asking the four local TV stations to pool, which three of them agreed to, and allowing maximum one staffer per outlet. “And if you want to bring your own TV camera but man it, that’s fine, too,” says Azzopardi. “Their job is difficult enough without having to man the camera and ask questions and try to get answers too. And that’s why I help facilitate it all.”

How will these daily briefings change the governor’s relationship with the press? The governor insists he’s not going anywhere. During the June 18 briefing, he said, “I’m not running for anything. Period. No president, no vice president, not President of Argentina, not President of Italy, not prime minister. I’m not doing anything. I’m not running for anything. I have one agenda, which is to work for you.” But of course, the increase in national press appearances could give New Yorkers a different idea. “He has said he doesn’t want a higher office, but you’re talking Rolling Stone covers, Vanity Fair covers, the Ellen show, nightly appearances,” says McKinley. “I don’t know if it’ll change his relation with the Albany press corps, but it has certainly changed his relationship with the national press corps, for many of which this is their first, or a fresh, look at him.”