We’re committed to keeping our readers informed.

We’ve removed our paywall from essential coronavirus news stories. Become a subscriber to support our journalists. Subscribe now.

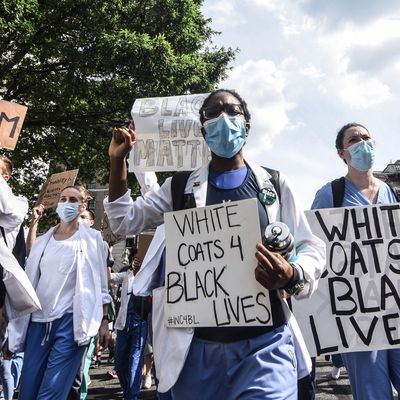

As demonstrations against police brutality engulfed the country, over a thousand public-health professionals came out in support of the protests in an open letter. One person who signed was Gregg Gonsalves, a professor of epidemiology at Yale and MacArthur genius who is no stranger to protest movements. As a “gay college dropout in the 1980s,” as he once put it, he got his start at ACT UP and went on to co-found the profoundly influential Treatment Action Group. In 2008, bearing recommendation letters from Larry Kramer and Anthony Fauci, he enrolled on a full scholarship to Yale to finish his degree, get a Ph.D., and stick around to teach at the crossroads of health, law, and justice.

This past spring, Gonsalves was briefly relieved to see Fauci and Deborah Birx, both familiar faces from the AIDS crisis, working on the federal response to the coronavirus. Having studied Mike Pence’s response to the HIV outbreak in an Indiana county, though, he was chilled to see the vice-president put in charge. “It took a decade for us to have 100,000 deaths from AIDS,” he told me. “Now, we’ve wrapped that up in the course of months, because you had an administration that was incomprehensibly incapable of confronting the tragedy that was unfolding right in front of them.” On Monday, we talked about whether epidemiologists have anything to apologize for, how it feels to be both insider and outsider in this time of crisis, and what the future of social distancing might look like post-protest. (This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and brevity.)

We’re at a moment of conservative backlash to public-health professionals. They accuse you and others of hypocrisy for backing the protests against police brutality while advocating shutdowns and social distancing. I want to ask you first what you think about the premise implied here — that the pointy-headed public-health people have been bossing people around.

You know, if only. If only the public-health people had been in charge. And that’s not just Republicans. Bill de Blasio was basically giving the hand to his department of public health; public health was marginalized even by ostensibly one of the top Democrats in the country. At the federal level, they all serve at the president’s pleasure. There were some very tough choices to be made, and often what the science says is not palatable to our leaders. Even now. In Connecticut, we’d love the governor to release people from prison, and he doesn’t want to do it. If we think about the inability of Governor Cuomo to confront the nursing industry, if we think about the meatpacking plants.

What about the accusation that because public-health professionals are sympathetic to the protests, they have created a double standard that it’s okay to protest police brutality and racism but it’s not okay to go to church or activities that conservatives prefer?

I’m willing to entertain good-faith arguments. I think many of these people just didn’t confront the administration on its failures that created a greater climate of risk. I’d ask, where have you been lately? Second of all, public-health experts — and we’re not a monolith, there’s plenty of differences of opinion — are saying, look, we cannot tell the tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, of people now marching around the world against police violence and systemic racism, go home and stay home. It’s just like telling people in 1982 stop having sex because there’s a virus among New York City or San Francisco or L.A. Public health is all about meeting people where they’re at. It doesn’t help to say police violence doesn’t matter. The health disparities that have killed tens of thousands of people over a half a century don’t matter. We are saying we understand it matters; they’re public-health issues too.

Then people say, well, you didn’t say that about the liberate protesters back in May. One, timing is everything. In March and April, the epidemic was raging in full flourish. Nobody was really talking about reopening back then, and there was little public reaction to the protests in the public-health community. But if I were in Virginia or Michigan back then, I’d be masked up with goggles and I’d be saying, hey, look, the economic effects of this pandemic are real, they’re acute, and many of us have been fighting tooth and nail to figure out how we can get our government to do what Germany and Denmark [are doing], which is more-robust support. [Yale Law School professor] Amy Kapcynzki and I wrote three pieces for the Boston Review where we articulated this — it’s about markets versus lives, not about the economy versus viruses. We understand what’s going on. I’d say to them, “Please put down the gun. And put on a mask.”

The better example was funerals and religious services. My friend [Harvard epidemiologist] Julia Marcus and I in early May did an interview with Michelle Goldberg at the New York Times, and I said, it’s pretty clear now that we can’t keep these strict lockdowns forever; we need look to what we called in the AIDS epidemic safer sex. I lost my father in November, my mother’s 86, and the prospect of going to somebody’s funeral is barely six months only in my personal lives. We’ve got to figure out how to do this in a safe way.

I think what’s going on with this kind of commentary is that it’s the old dance that conservatives try to do: It’s the liberal elites on the coasts who don’t understand the real people in the heartland of America.

That must be funny for you, since you were an outsider for so long.

A lot of the hate mail is like, you elites. Hello, I dropped out of college in the 80s. I waited tables, and then I got a little bit of money to be an AIDS activist. Yale paid for my bachelor’s degree … If anybody wanted to understand my history, they could look. I was talking to someone who has been part of this discussion, and they said, I didn’t know you were HIV-positive. I said, come to the clue phone.

What strikes me is that some of the same people who are angry about the shutdowns oppose harm reduction when it comes to, say, sexual health or drug use.

Harm reduction for me, abstinence for you.

There was also some notion that communities of color didn’t understand the risks and somehow we should have been there to instruct them. There are plenty of people marching who had to be one two or three degrees of separation of someone who died of COVID … I realize some of the people who have been saying this in public health and health care are very afraid that we’re going to see ERs and ICUs overwhelmed again. Nobody’s under the assumption that these protests are risk-free. But the point is, what are you going to do, should I write an op-ed for a newspaper that says stop protesting? You figure out where people are and you work with them.

I got so heartened when I went to the protest at New Haven. I think I saw one or two people in the crowd of 5,000 without masks. A lot of people understand what the risks are, not only to them but to their communities. People are adjudicating their own risk level and comfort level at these protests. If you’re a public-health person, you encourage that; You say, you can do more. San Francisco is starting to set up testing sites for protests. We should advocate for that. Let’s hand out palm cards at all the protests saying, here’s your closest testing site. If we’d had a rational national conversation, we would have been able work through these issues really early on. We never have gotten anywhere close to a national consensus on testing, tracing, scaling up socioeconomic support.

I do think there is a real loss of trust when people are hearing so much conflicting information about masks, or about surface transmission, or about indoor versus outdoor. What happened?

In the beginning, this was a new virus and we were in the fog of the pandemic. All I can remember from March and April is, we were trying to get masks to people in the hospitals. Medical workers were using panty shields and bandannas. People were making face shields. The CDC was AWOL. The lights were off at the CDC in January and February. The agency that should have told us all of this were bound and gagged. Nancy Messonier, you heard from her once and never heard from her again. The WHO guidance didn’t advocate for masks until June 5.

I think what was happening in February and March is that we were using generic public-health guidance … The reason you start thinking about harm reduction is that we’re starting to learn more. There’s the abundance-of-caution stuff that was happening early on because of reasonable fear and lack of information among organizations from the WHO downwards. And there was a worry about how this was going to play out in dissuading people from other measures like washing hands. It reminds me of the argument with HIV that safer sex or PrEP was going to be disinhibiting. Or that needle exchange promotes drug use.

You started out as self-taught. What do you think of all the people outside your field — in tech, politics — trying their hands at building models and making predictions? Does it make your head explode?

I spent a lot of time outside the university and was very always aware of what I didn’t know. Does it make me happy that a lot of people are interested in public-health modeling and how public health works? That’s great. There are some people in the data science world who are building websites who have been super-grateful when I say, okay, let’s talk about how you got those inputs in your model. What I have no time for is people who are actually not really engaged but they’ll use their math skills to bludgeon you with a point that they have no commitment to following through on. Twitter has a lot of that.

Where do you think things go from here now that the genie is out of the bottle with social distancing?

The protests are one thing. Warm weather hits. If you walk around New Haven, you see there are more cars in the road, that parking lots of certain stores that were open the whole time are fuller now. You go to the park and see people hanging out, some with masks and some not. The data shows that people took up the call to social distance early on, before being asked to, and now people are starting to relax more. They’re still afraid of certain kinds of public gatherings and are still exercising caution. But my big fear is that we see a second wave, a third wave, a fourth wave, and it’s going to be harder to get people to go for the full lockdown again. We’re in for a long, long ride with this pandemic. We talked about safer sex in the ’80s, and now we have to talk about safer living.