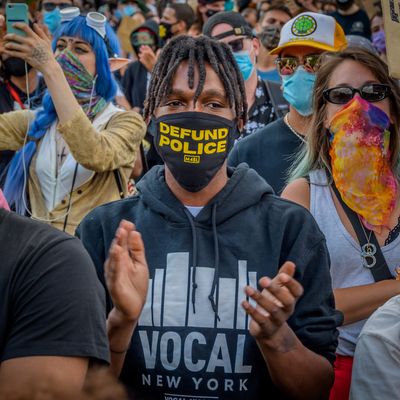

“Defund the police” has become a rallying cry for recent protests, but several different explanations have been offered for what it actually means. The semantic dispute reveals key philosophical differences among its proclaimers: The abolitionists who coined the term see gutting police budgets as one step toward a policeless society; others who’ve adopted it see policing as redeemable and worth preserving — a common view that much evidence suggests is folly.

This has been a source of confusion and contention. In the weeks since a Minneapolis police officer knelt on George Floyd’s neck and killed him, social media and news broadcasts have been awash in pundits and pols claiming that protesters shouting “Defund the police!” don’t really mean it. What they do mean varies depending on the source. It might be “budget priorities [for black and brown communities] that white communities have already created for themselves,” like funding education over law enforcement; it might be a maximalist demand aimed at securing modest tweaks to the status quo, like “reform … [and] good policing.” The confusion is understandable; people have freighted the term with their own agendas. Sympathetic officials, eager to make the protesters’ grievances sound uncontroversial, have sought to reconstitute it in more palatable terms for a wary public. Detractors and opponents see these conflicting approaches as signs that dissidents either don’t know what they want, or desire anarchy. Armchair political strategists object to its branding, complaining that its radical posture makes good proposals made in its name seem scary and divisive.

Then there are the abolitionists, who introduced the concept into the lexicon. Their intention remains as stated: They want to take money away from the police. The analysis that informs them is robust and long held. They view police violence as intolerable but inevitable as long as the institution exists. “Unequal enforcement and violence aren’t aberrations: they are a necessary part of the job,” reads an explanation at A World Without Police, an online resource kept by an anonymous global abolitionist collective. Supporting evidence abounds; even the best-behaved police departments enforce the law with severe racial and class asymmetry. Anti-bias training yields little reprieve. Steady rates of police killings nationwide, despite significant reforms being implemented, testify daily to the institution’s imperviousness to change. In the communities cited most often to illustrate policing’s necessity — typically poor, usually black, with homicide rates well above the national average — decades of alternating neglect and over-policing have proved it a failed model for keeping the peace, but an effective one for subjecting children and traumatized adults to harassment and criminalization.

The result is social combustion visible from Minnesota to Los Angeles to New York. Critics broadly agree that a logical first response is to narrow the police’s purview; others want fewer of them altogether, to thin their ranks toward reinvesting in social welfare. “What about rape and murder?” is the common retort, but by most estimates, acts of violence consume less than 10 percent of the average officer’s time on duty. Even in severe circumstances like homicide, police have a middling track record: The murder clearance rate hovers around 50 percent in the typical American city. The average officer spends 90 percent or more of their time addressing infractions of administrative codes — rules dictating how and where Americans sit, walk, eat, drink, drive, and participate in commerce. Most civilian contact with the police comes during traffic-related incidents, like collisions or police-initiated stops. Armed officers have become the front line for dealing with homelessness, mental health crises, substance abuse problems — all issues that a social worker could do more effectively and less brutally.

But revising the police’s job description is where much of the agreement ends. Abolitionists frame their belief system simultaneously as a goal, a process, and a practice. It’s a holistic vision that takes up the question, “How might society look if criminal punishment wasn’t an available method of recourse?” None of its desired outcomes are supposed to happen in a vacuum. Few abolitionists foresee a society without police that doesn’t also lack prisons, or feature sustained countervailing investments in housing, employment, education, substance abuse treatment, health care, and new standards around conflict mediation and addressing interpersonal violence. Far from unimaginable, such a world gets hinted at daily. Abolitionists point to how millions of people resolve disputes and violent conflicts all the time without police intervention, sometimes by simply declining to involve them. Others work to replace law enforcement’s mediative function with community support networks, crisis centers, and self-defense groups — a model for the future that abolitionists envision, typically incubated by and within the same communities deemed most in need of more policing. Others still are fortunate to live in circumstances where their social and material needs are so taken care of that they might not see an unsolicited police officer for months.

The idea is to synthesize these realities at scale. This creates tension with strategies that seek merely to change how policing announces itself, often while expanding its reach. “Community policing,” more training, more aggressive criminal prosecution of officers who behave badly — to abolitionists, these are proposals that either expand policing by integrating it more thoroughly into communities and giving it a more varied operational tool kit, or lend it more legitimacy by feeding America’s jails and prisons. Abolitionist alternatives include making police liable for misconduct settlements, demilitarizing them, and reducing the size of their departments, partly through defunding, partly by refusing to rehire officers who’ve been involved in excessive force incidents and disallowing paid leave for those under investigation. The rubric is whether a policy shrinks the scale of policing, reduces the weapons at its disposal, and challenges the notion that the police increase public safety.

This doesn’t mean “better” policing, to quote Washington, D.C., mayor Muriel Bowser. It doesn’t mean body cameras or choke-hold bans, neither of which stop abuse. Nor does it mean retraining or teaching police to recognize the prejudices to which they’ll revert the second they panic. It certainly doesn’t mean more money. Law enforcement already consumes more than half of the latest Los Angeles city budget; the NYPD’s just topped $6 billion. (Both have since been reduced in response to the protests.) This investment is inseparable from the divestment endured in the areas most likely to make it redundant, like public health and housing. Meanwhile, Eric Garner was killed by choke hold despite New York City’s choke-hold ban. Minneapolis police were a model of reform until Derek Chauvin crushed a man’s neck while three of his colleagues stood guard, in defiance of department policy compelling them to intervene. Even the celebrated Camden County Police in New Jersey — formerly the Camden police, disbanded and rebuilt in a flurry of misconduct and austerity demands in 2013 — shows what “community policing” most often looks like: more officers, more surveillance, and a renewed emphasis on “broken windows” law enforcement, cycling people through the criminal-legal system over citations, fines, and misdemeanors.

A question that abolitionists often ask is whether the current system is actually delivering for people who wish to resolve harm. Murder, rape — both still happen regularly, despite no shortage of police officers or legal consequences. Current methods of punishment succeed mostly in facilitating more of both, often by rerouting them into jails and prisons. The dilemma is whether that’s tolerable. How much pain is necessary to compensate for our own? Conventional wisdom holds that people who cause harm deserve harm directed back at them ad infinitum — if harm is done at all; police regularly introduce harm where none, or mere nuisance, existed before.

This is where abolition is most accessible as a framework — even for those who don’t consider themselves adherents. If your horizon is reform, you’re more likely to tolerate harm in the course of securing it; if you think the system is redeemable but falling shy of its potential, you’ll fight to redeem it, often through tweaks, overhauls, and even expansions that have consistently failed, and if you’re not careful, make matters worse. If your horizon is abolition, though, anchored by a refusal to greet harm with greater harm, you’re left with little choice but to dismantle harmful systems — to recognize that law enforcement’s excesses are by design, and to set your goals further afield. You won’t always succeed; the amount of public buy-in and the sheer number of mutually reinforcing changes required to make any single component of abolition work can seem insurmountable. Abolitionists readily admit their goal is a process with no precedent. Some disagree about how to get there. Some foresee an endgame that includes a “small, specialized class of public servants whose job is to respond to violent crimes” — not police, exactly, but something that fills one of their rarer functions.

But for most, the key mandate is that the specifics derive from the commitment. This is why the dispute over what “defund the police” means matters; efforts made in its name risk reinforcing what they seek to change if severed from its abolitionist roots. Some people would prefer that. Others cite pragmatism to rationalize asking for less. This isn’t to say that incremental change is unimportant; on the contrary, such a monumental task requires it. But wherever there’s agreement that police violence is the problem, and not the solution, aiming to uproot it rather than mitigate it isn’t just prudent, no matter how utopian or unpopular. It’s necessary. Abolition is an opportunity to reimagine how society responds to harm. Past efforts have been disastrous. Even if we’re not ready to demand a new world, we can see more from orbit than we do from underground.