New York Is Committed to Covering This Essential Moment

We’ve removed our paywall from this and other stories about police brutality and systemic racism. Consider becoming a subscriber to support our journalists.

When Minneapolis students go back to school in the fall, they’ll find the hallways free of police. The local school board announced on June 2 that it would cancel its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department. In doing so, officials satisfied a long-standing demand of the local teachers union and other local activists. “Kind of overnight, people woke up,” said Greta Callahan, the president-elect of the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, Local 59.

“We don’t need to punish anyone for not coming along in the past, because we’re here right now,” she added.

The path to police-free schools is an arduous one, as the example of Minneapolis shows. There, it took a murder and a nationwide protest movement to get cops out of city schools. The practice is entrenched, with uniformed and sometimes armed police a common sight in American public schools. Around 30 percent of the nation’s school districts used police, known as school resource officers, in 2013. The Oakland Unified School District in California even has its own police department.

But not, perhaps, for much longer. Oakland school officials will soon vote on a resolution that would eliminate its in-house police. If the measure passes, they’ll follow an example set not only by Minneapolis but also by Portland, Oregon, and Charlottesville, Virginia, too. Portland’s school superintendent Guadalupe Guerrero announced on June 4 that the city’s public high schools will no longer use school resource officers. On Thursday, the Charlottesville public school district did the same. Elsewhere, teachers unions in Madison, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Seattle have either passed new resolutions or intensified older demands for cop-free schools.

Educators who want resource officers out of their schools aren’t necessarily police abolitionists, but their goals and convictions overlap. In lieu of cops, they want more nurses and social workers. Madison Teachers, Inc., conditioned its support for cop-free schools on the hiring of more support staff. “If we remove police officers from our schools, but do not adequately staff those same schools with social workers, nurses, counselors, and psychologists, we are perpetuating harm upon our most vulnerable young people,” the union said in a public statement.

The Madison union had historically supported the use of resource officers in schools. In other cities, unions had been organizing alongside community groups against policing in schools for years. “This is work our union has been doing since 2015, in coalition with community groups, grassroots organizations, and students,” explained Stacy Davis Gates, the vice-president of the Chicago Teachers Union. Earlier this week, union members marched alongside students and other activists to call on the school district to end its contract with the Chicago Police Department. Lori Lightfoot, the city’s Democratic mayor, may be an obstacle. Asked directly by the local press if she’d back calls to take police out of schools, Lightfoot was blunt. “Yeah, we’re not gonna do that,” she said. “Unfortunately, we need security in our schools.”

But security has costs that are both financial and psychological. According to Chicago’s PBS affiliate, WTTW.com, the school district spends about $33 million a year on its contract with the police department. The city is prepared to spend another $100 million to build a new training academy for police and other first responders — a major point of conflict between Lightfoot, the teachers union, and other local advocacy groups, many of them led by young people. “You have GoodKids MadCity. You have BYP100. You have Assata’s Daughters. You have a number of community groups throughout Chicago that are black led, that are youth led, that are clear about what they need to see in their schools,” Gates said, ticking off the groups one by one. All believe the money the city invests in policing could be better spent elsewhere. “They are very clear about saying that investment should be a part of their school communities and the neighborhoods in which they reside, and we support them,” she added.

Minneapolis educators feel similarly dismayed by the fiscal priorities of city and state governments. “We are $5 billion underfunded in Minnesota,” Callahan explained. “We really believe that we wouldn’t need police officers in our schools if our students were supported. If we had art. If we had counselors. We really want that money to be used to support our students and in a safe, nonthreatening way.”

The transfer of public wealth from social services to policing brings with it a transfer of power, too. It keeps old hierarchies alive, then reproduces them anew for each generation. Our national overreliance on the police burdens not just taxpayers, but children, for whom the presence of a school resource officer may be no guarantee of security at all. School police are responsible for everything from breaking up fights to fighting off gunmen. They can also arrest students — providing, for many, their first stop on the school-to-prison pipeline. Police arrested 92,000 children in school during the 2011–2012 academic year alone, according to data from the Department of Education. Black students are overrepresented not just in rates of arrest, but also in rates of suspensions and expulsions, often for minor behavioral offenses.

Proponents of police in school, like Lightfoot, argue that officers keep campuses safe. That view is popular. Parents, for example, largely support the presence of armed police in school, as one poll from PDK International reported in 2018. With gun violence a looming threat and political solutions a distant hope, a police officer in school might look, to many, like a necessary step. But officers are responsible for their own acts of violence. Viral videos that show officers beating or arresting children as young as 6 have led occasionally to terminations, but not to police-free schools. In the absence of sensible gun control, or a functional safety net, public officials fall back on force. That creates significant headwinds for educators and teachers unions that think their students are safer, and learn better, without the threat of juvenile detention hovering nearby.

Lightfoot isn’t the only major Democratic mayor standing between teachers and cop-free schools. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio also said he thinks the police are still necessary additions to campus. “I’m thinking about all the parents I heard from at town-hall meetings all over the city who are worried about the safety of their kids in schools,” he told NY1.com this month. “I’m thinking about the weapons that had to be seized. It’s not just one way or another.” Though de Blasio has said he plans to cut some funding for the NYPD and redirect it to social services, including education, it’s not yet clear how much money schools can expect to receive. His change of heart is also notably recent. His first budget proposal, introduced in April, would cut education funding by $827 million.

Educators and teachers unions who want the police out of schools also have to worry about more than recalcitrant mayors and City Councils. They’ll have to pressure the rest of the labor movement to take up their cause. The debate over police in schools unfolds within another, related conflict within the labor movement itself. Other unionized workers are questioning the cops in their midst.

On June 8, the executive council of the Writers Guild of America, East, unanimously passed a resolution urging the AFL-CIO to expel the International Union of Police Associations, or IUPA. (The WGAE and the IUPA are both part of the labor federation, and so is the NewsGuild, which represents the editorial employees of New York Magazine.) But some AFL-CIO leaders, including its president Richard Trumka, have resisted calls to expel the IUPA. The federation’s general board subsequently adopted a set of recommendations intended to encourage the IUPA to reform itself from within. In the same statement, the federation announced that “we respectfully take a different view when it comes to the call for the AFL-CIO to cut ties with IUPA.” Sara Nelson, the president of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, later noted on Twitter that the general board did not actually vote on the WGAE resolution.

Not all police unions belong to the AFL-CIO. Neither do all unionized educators. But the American Federation of Teachers does belong to the federation, and internally, it lacks consensus over the necessity of cop-free schools. Reached by phone during a vigil for George Floyd, AFT’s president, Randi Weingarten, told Intelligencer that her union “has had the position that policing has to change.” But she characterizes the specific question of removing police from school as a decision best left to individual locals. “If you talk to people in schools where there has been a school shooting, they want police,” she said. “But, you know, even if you have police, it has to change to community policing.”

“Having said that, we believe that police and school resource officers should be mentors, not enforcers, that you can no longer have zero-tolerance discipline policies. That you need to have restorative justice,” she added.

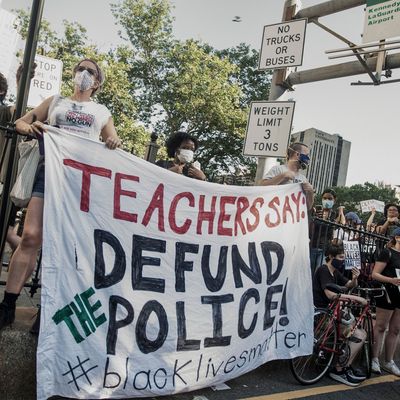

In New York City, this internal debate recently played out in public. On June 6, the Movement of Rank and File Educators, or MORE, caucus of the United Federation of Teachers joined community groups for a rally in front of the union’s headquarters. From there, they marched to the Department of Education calling for the removal of cops from schools — a demand that the UFT has not formally embraced.

The MORE caucus didn’t respond to a request for comment by press time. But in a statement to Intelligencer, UFT president Michael Mulgrew said, “The safety of students and staff is our first priority. If people have an alternative suggestion to better ensure that safety, we are willing to discuss it.” The UFT previously participated in a city-run Diversity Advisory Group, where it recommended the Department of Education conduct a transition study on the logistics of taking school security over from the NYPD.

But after Minneapolis, neutrality might be difficult to sustain. So might incremental approaches to reform. Floyd’s killing focused decades of building outrage, and in its wake, cries for change have become more insistent and more difficult to ignore. For educators, who were reeling from the consequences of the coronavirus when protests gripped the nation, the moment is a crucible. “I truly believe that if we double down on public education, so many of society’s issues will get better,” Callahan said. “We can also educate more people about what is happening, and how we can collectively make change.”