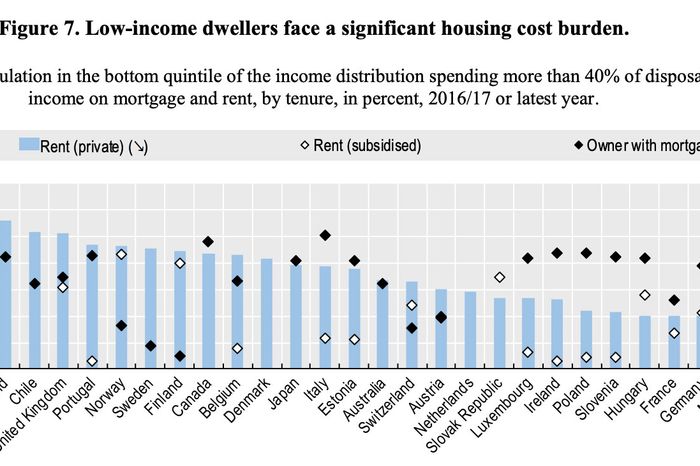

The wealthiest country in human history has trouble keeping its people housed, even in good times. In 2017, the United States boasted one of the strongest economies in the world, and nearly half of its tenants were rent burdened. A majority of households in the bottom quintile of our nation’s income distribution give more than 40 percent of their disposable income to landlords each month. Only three other developed countries force their poor to shoulder heavier housing costs.

In times of crisis, the unaffordability of American housing is exacerbated by our “just in time” socioeconomic model: Steady GDP growth is the duct tape holding together this jerry-rigged social order in which low-income Americans have little to no emergency savings, many basic welfare benefits are contingent on employment, and the threadbare safety is patchy by design. This top-heavy, gold-plated jalopy of a political economy can pass as road safe in fair weather; try to ride it through a once-in-a-century epidemiological storm and it starts to break apart.

Between 2006 and 2014, about 10 million Americans lost their homes to the foreclosure crisis. Today, upwards of 20 million U.S. renters are poised to be evicted between now and September, according to Emily Benfer, the chair of the American Bar Association’s Task Force Committee on Eviction.

At present, the impending flood of evictions is partially dammed by a federal moratorium that covers one-fourth of all renters, the $600 federal unemployment insurance bonus, and the recent dispersion of $1,200 coronavirus relief checks. But even with these protections, a great many renters are being washed out of their homes while millions more accrue onerous debts. Roughly one-third of U.S. households have not made their full housing payments for July, according to a survey by the online retail platform Apartment List. In New York City, one-quarter of all renters haven’t paid their landlords since March.

This is in part because fiscal aid has not reached everyone in need (many state unemployment insurance systems have failed to keep pace with applications; many workers do not qualify for federal unemployment benefits; and others were reliant on informal work), and the federal moratorium on evictions does not cover most renters. But it is also because the federal moratorium doesn’t actually have an enforcement mechanism. Fifteen states have passed legislation requiring landlords to verify that their buildings aren’t covered by the federal ban before seeking to remove their tenants. In all other states, the obligation lies with the tenant, which is to say a renter must verify that their building is covered by the moratorium and prove it in court.

People facing eviction do not generally have much disposable income available to cover legal bills; in fact, many struggle to muster the data or internet connection necessary for attending the videoconference hearings that have taken the place of eviction courts throughout much of the country. A Washington Post account of one embattled renter’s attempt to avert eviction illustrates the pathologies of this process:

Judge Yvonne Williams, glasses snuggled tight to the blue mask covering most of her face, peered into the camera in her Texas courtroom recently to press a renter about the more than $4,000 she owed her landlord.

“What do you have toward the rent?” Williams asked.

The renter appeared on another shaky screen from a dark room and explained that she had been furloughed as the spread of the novel coronavirus shut down much of the U.S. economy. But she had three kids and nowhere to go, the renter said, and was working to raise the money, which included more than $1,000 in late fees.

… During the hearing, the judge was asked whether the renter might be covered by the moratorium, which doesn’t expire until late July. But Williams shrugged off the question. (The Washington Post viewed the hearing online.)

“I am not familiar with that, but if someone will show me the law on that, I will certainly entertain that,” she responded. “Right now, I am going to give them the eviction … as unfortunate as it is.”

According to a search on Fannie Mae’s website, the building is covered by the moratorium.

Absent congressional action, enhanced unemployment benefits will expire at the end of this month, while the federal eviction moratorium will be lifted in the fall. As of this writing, congressional Republicans are committed to reducing unemployment benefits and blocking an extension of existing rental protections.

For their part, House Democrats have passed legislation establishing a $100 billion rental-assistance program, while Senator Elizabeth Warren has proposed expanding the number of households covered by the federal eviction moratorium and extending that ban into March 2021.

If no action is taken, up to 28 million Americans could be thrown out of their homes by October, according to Benfer. The victims of such a catastrophic social failure will extend well beyond the ranks of the displaced. As Bloomberg’s Noah Smith writes:

When a landlord evicts a tenant, they need someone else to move in relatively quickly. If no one does, it means a financial loss for the landlord and an economic loss for the country as a whole because the apartment is going to waste. The time and expense that the evicted tenant has to spend moving to a new place results in an additional economic loss…Units whose tenants are evicted will probably sit empty for many months until the crisis is past, while the evicted low-income people will either crowd in with family or become homeless, increasing the risk of coronavirus spread. This is bad from both an economic and a public-health standpoint.

The fiscal cost of keeping cash-strapped Americans in their homes — and unburdened by back rent — may well be lower than that of allowing them to be thrown onto the streets by the tens of millions. The human costs of the latter, meanwhile, are higher than any decent society could afford.