In very recent years, the ancient dilatory tactic of the filibuster has been abused (mostly, though not exclusively, by Republicans) to create a de facto 60-vote supermajority requirement for virtually all major legislation in the Senate. For some older Americans, however, the filibuster is indelibly associated with the southern regional resistance to the civil-rights movement. Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the history of congressional action to dismantle Jim Crow occurred on June 10, 1964, when proponents of what was to become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 mustered 67 votes to invoke cloture and end the filibuster orchestrated by southern leader Richard B. Russell of Georgia (for whom one of the three Senate office buildings is named).

In 1975, the Senate reduced the number of votes required for cloture from 67 to 60 votes. Alongside the recent routinization of the filibuster, both parties have combined to eliminate its use with respect to executive and judicial nominations.

But there’s been much solid bipartisan resistance to elimination of the legislative filibuster. As recently as 2017, 61 senators, including 32 Democrats and 29 Republicans, signed a letter “opposing any effort to curtail the existing rights and prerogatives of Senators to engage in full, robust, and extended debate as we consider legislation.”

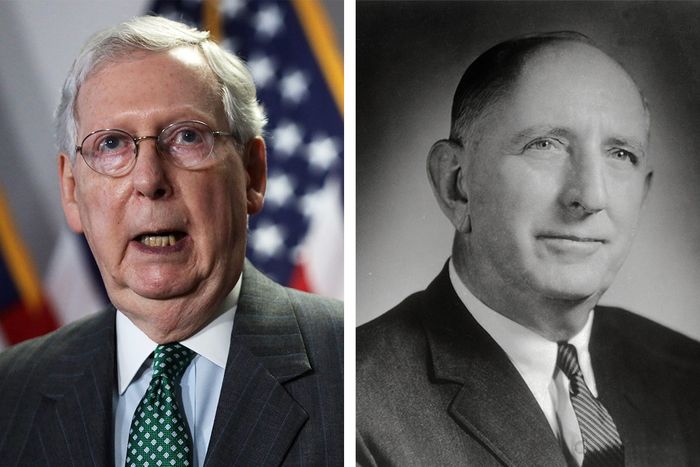

Currently, however, as Democrats look ahead to the increasing possibility of a Biden administration and a Democratic Senate, memories of how Mitch McConnell used the filibuster to hamstring the Obama administration have spurred some reconsideration of the traditionalist stance. Chris Coons, who along with Susan Collins circulated the above-mentioned pro-filibuster letter, has expressed second thoughts about exposing the agenda of his friend Joe Biden to Senate obstruction. Even Joe Manchin, the Democrat least inclined to toe the party line, seems frustrated with how “the place [the Senate] isn’t working.”

Still, if (as is likely) Republicans shift toward party-line defense of a supermajority requirement as they move into the minority, it would take lockstep support for filibuster reform among Democrats to make it happen. That might still be a bridge too far if it’s a matter of enacting sweeping progressive legislation on health care or climate change. But as Ron Brownstein explains at The Atlantic, the perfect mobilizing device for filibuster reform might be the old nemesis of racial injustice:

[A]fter this spring’s nationwide outpouring of protest following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, many Democrats believe that if the party wins unified control, issues of racial inequity and civil rights may create the greatest pressure yet to eliminate the filibuster. That pressure will only grow if, as many voices are already urging, Democrats brand some or all of their voting-rights agenda as a tribute to the civil-rights pioneer and longtime Representative John Lewis, who died on Friday. Already, Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont said he would reintroduce one such bill to name it for Lewis, who he described as “my hero.”

The heavy focus on voting rights during the coronavirus pandemic and in the runup to November could certainly make legislation to restore the elements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 gutted by the Supreme Court in 2013 (which the House passed last year) a partywide Democratic crusade in the next Congress worthy of an associated effort to kill the filibuster. But a broader racial-justice push could be combined with voting rights in a way that places great moral pressure on Senate Democrats to reciprocate the exceptional loyalty of Black voters, notes Brownstein:

Leaders of the burgeoning racial-justice movement are unequivocal in warning Senate Democratic leaders that they risk an eruption if they achieve unified control of government yet allow Republican filibusters to kill civil-rights initiatives that pass the House, as bills on police reform, voting, and other issues have in this session.

That “will be unacceptable,” Rashad Robinson, the executive director of Color of Change, a leading racial-justice organization, told me. “It will be unacceptable to people who have waited a long time. It will be unacceptable to people who are already skeptical of electoral politics. It will be unacceptable that a body that is deeply unrepresentative of a diverse America is telling people to wait more time.”

This last observation by Robinson suggests another reason racial-justice legislation might provide the best available reason for filibuster reform: It would help Democrats rightly paint McConnell and his Republicans as the spiritual heirs of the southern racists who deployed the filibuster to impose their own tyranny on the minority for so many years. If all this is happening at a time when Donald Trump no longer occupies the White House, there could even be some Republican support for turning the page on a GOP rooted in older white voter resistance to a changing country.

Once the filibuster is gone or radically curtailed, of course, the door would be open in a Democratic-controlled Senate to enact all sorts of progressive legislation. But the first insistent knock on the door ought to be by and on behalf of those who have waited so long for equal rights.