On the final day of its current term, the U.S. Supreme Court today handed down a pair of decisions in cases involving efforts to pry loose the president’s financial and tax records. Both involved 7-2 decisions, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing for the majority, and the Court’s two most conservative justices (Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito) dissenting. And in both, the Court rejected sweeping Trump claims of immunity from state grand-jury and congressional subpoenas while ordering further proceedings that will probably delay any disclosure of the records until after the November elections.

In the state grand-jury case, Trump v. Vance, all nine justices rejected Trump’s claim of absolute immunity from state criminal prosecutions, though the two dissenters would have invited Trump to make a constitutional argument against enforcement of the subpoena on more specific grounds of impairment of presidential prerogatives. The majority opinion from Roberts (in which the Court’s four liberals silently joined; justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch concurred while also noting Trump might raise successful objections to the subpoena later) simply dismissed the claim that the president’s constitutional role gave him any special protection from state grand-jury proceedings involving his nonofficial records, sending the case back to the lower courts and ultimately to the state court.

It can reasonably be expected that Cyrus Vance Jr. will be able to execute his subpoena at some point soon, though grand-jury secrecy rules also mean public disclosure of Trump’s tax returns or financial records is very unlikely to occur before November.

Next up was Trump v. Mazars, the closely watched case weighing congressional subpoenas of the president’s financial records and the final decision of the Supreme Court’s term. There, the justices handed Trump another legal setback but coupled it with a tactical victory.

Writing for the majority, Roberts again rejected Trump’s maximalist argument that his records were protected from disclosure to Congress absent a clear showing of legitimate legislative interest in them. In particular, Roberts pointed out that the records in question were not official documents that could be shielded by claims of executive privilege. But he also concluded that the district and circuit courts that ruled in favor of the congressional subpoenas had inadequately addressed “separation of powers” concerns raised by Trump’s lawyers. So the effect was to start the litigation all over under the new balancing test Roberts announced, as SCOTUSblog analyst Amy Howe explained:

[T]his is basically a Goldilocks approach. The test proposed by the president and the SG [Solicitor General] is too tough. The House test is too lax. The court outlines a set of “special considerations” that the courts should take into account on remand and sends the cases back to the lower courts for further consideration. So I am going to take back my [initial] suggestion that this is more of a win for the president than Vance — I think it’s basically the same. In this set of cases and the Vance case, we are going to have more litigation, and no one is going to see any financial documents anytime soon.

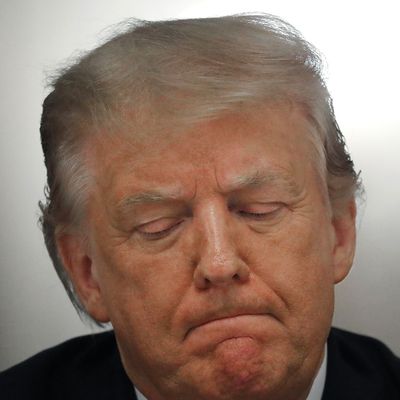

While both decisions had the effect of keeping Trump’s records out of the public eye while he is battling for reelection, his angry reaction seemed to focus on the rebuff of his prerogatives as president:

He seems particularly worried about the implications of Vance:

But then again, Trump can scour the country and never find a judge who is going to agree with his stated belief that Article II of the Constitution (enumerating presidential powers) means “I can do anything I want.”

It’s true, however, that Vance represents a clear and novel rebuff of expansive views of executive immunity. That’s certainly how the New York Times’ legal expert, Adam Liptak, viewed it:

The court’s decision in favor of the New York prosecutors was a major statement on the scope and limits of presidential power, one that will take its place with landmark rulings that required President Richard M. Nixon to turn over tapes of Oval Office conversations and forced President Bill Clinton to provide evidence in a sexual harassment suit.

But the current pursuit for truth and transparency involving Trump’s shadowy personal finances and suspect deal-making may simply become moot in the court of public opinion by November.