More than 1.1 million acres of the State of California have been burned by wildfires since a “lightning siege” started hundreds of fires throughout the state a little more than a week ago. To the north and south of the Bay Area, two complexes, or groups of fires, are now the second and third biggest fires in the state’s recorded history — and they and several other large wildfires, which grew at an unprecedented pace and remain largely uncontained, will continue to expand in the coming days. The good news, at least over the past 24 hours, is that the region dodged a major bullet when a weather system that could have produced more lightning strikes and dangerous winds — both starting new fires and spreading existing ones — did not do that.

Every Bay Area county except San Francisco has been struck by the fires, and the smoke they’ve produced has enveloped much of the state and the western half of the country, promoting widespread air-quality warnings. It’s not yet clear what effect the fires and smoke will have on California’s efforts to suppress the coronavirus, or on the severity of subsequent COVID-19 cases in the affected regions, but it won’t be good. The pandemic is already complicating evacuations and firefighting efforts, which have been stretched so thin that some fires have had to be left to burn, and may continue to for weeks. On Saturday, California governor Gavin Newsom announced that the White House had approved his request for a presidential major-disaster declaration.

More than 14,000 firefighters are battling two dozen fires across the state, according to the state’s fire agency, CAL Fire. Thanks to climate change–fueled weather conditions, including a historic heat wave, California has been hit by more than 12,000 lightning strikes since August 15, starting at least 615 new wildfires. (That was CAL Fire’s count; another analysis found that there were more than 20,200 cloud-to-ground lightning strikes in the state between August 15 and August 19.) There have been reports of local officials scrambling, even begging, for more resources after requests were turned down by Cal Fire, which has already shifted its efforts to prioritize the protection of lives and property. More favorable weather conditions helped fire crews make some progress against the fires over the weekend, but the battles are far from over.

More than 250,000 people live in the areas under evacuation orders due to the wildfires, most of which are concentrated in Northern and central California. Over 1,000 structures have already been lost, while more than 54,000 additional structures remain threatened, and at least seven people have been killed.

And the fire season is just getting started:

Too many fires that are too big, and there are nowhere near enough resources to fight them

More than 14,000 firefighting personnel, some of whom are working 24-hour shifts, are trying to take on more than two dozen California wildfires, including the three largest ones: the LNU, SCU, and CZU Complex Fires in Northern California. Some firefighters have reportedly been on the front lines for as long as 72 hours. In addition, 2,400 fire engines (including 96 percent of CAL Fire’s) have been deployed in the fight, as have about 200 aircraft, and the National Guard and U.S. military have also sent in resources, including helicopter crews, C-130 air tankers, and hastily trained ground crews. Governor Newsom said Saturday that ten states are sending personnel and equipment to help, and he has also reached out to Canada and Australia for whatever they can spare.

And it’s nowhere near enough.

As an illustration of how overstretched Cal Fire is dealing with the current fires, in 2019, three times as many firefighters were deployed to battle the 77,000-acre Kincade Fire in Sonoma County as have been deployed to fight the LNU Complex, which is more than four times Kincade’s size.

Cal Fire has been forced to reorganize its efforts on the fly and adopt a triage system when deciding which fires to confront, as the Associated Press reported Saturday:

With firefighting resources tight, homes in remote, hard-to-get-to places burned unattended. Cal Fire Chief Mark Brunton pleaded with residents to quit battling fires on their own, saying that just causes more problems for the professionals. “We had last night three separate rescues that pulled our vital, very few resources away,” he said …

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Mike Smith said typically a wildfire of the size burning through the region would have 10 or even 20 times as many firefighters. “We are doing absolutely everything we can,” he said.

The Los Angeles Times has more on the shortages and pressure points:

In some places, officials said they were being turned down for state help and left to beg equipment and manpower from volunteers and local agencies …

With blazes overwhelming the crews available, fire experts say state officials are now being forced to prioritize which fires will get resources, and to change how equipment and crews will be used. Though officials often try to build defensible lines to contain blazes, fire experts said the focus was now on saving lives and structures. That means the current blazes could burn for weeks.

“At the statewide level, we do get into this mode where we start wondering where the biggest loss is going to be, what’s the highest priority, and that is where the resources are going to go,” said Lenya Quinn-Davidson, a fire specialist with the UC Cooperative Extension.

With resources stretched so thin, CAL Fire officials are dreading the possibility of more lightning storms leading to more fires. In addition — though it appears help will be arriving from neighboring states — Arizona, Oregon, Colorado, and Washington State currently have their own wildfires to worry about, too. All told, more than 1.6 million acres of America have already burned this year, and as of this weekend there were 93 active fires across 13 states.

The perfect firestorm

Here is how UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain tried to explain the scale of what happened last week, starting with the extreme weather that preceded it:

[M]id-way through this extreme heat event [the ongoing record-breaking heat wave, caused by a “heat dome”], remnant moisture and instability from former Tropical Storm Elida combined with a robust easterly wave over California to generate one of the most intense summer thunderstorm events of the past 20 years across the San Francisco Bay Area. Most of the coastal portion of the Bay Area experienced intense and even locally violent wind gusts during this thunderstorm event. Many places saw 40-50 mph gusts, but there were a few places that logged winds of 65-75 mph as these powerful storms moved ashore. Much of the SF Bay Area was under a multi-hour Severe Thunderstorm Warning by the NWS for the first time I can remember. Multiple places also experienced Midwest-style convective “heat bursts” — in which rapid collapse of thunderstorm updrafts caused air parcels aloft to plunge to the surface and warm to extreme levels.

And then there came the lightning. Over 11,000 strikes were recorded over northern California over a 36 hour period, and many of these occurred pretty close to the coast (though some did extend inland over the Sacramento Valley and its foothills). As feared, unusually dry vegetation following an extremely dry winter and in the midst of a record heatwave acted as tinder — and many of these lightning strikes ignited wildfires. Over 350 lightning fires were reported over NorCal this week. But the number of fires is actually not the most problematic aspect of this event — it’s the astonishing speed with which these fires grew and their relative proximity to many heavily populated areas …

I’m essentially at a loss for words to describe the scope of the lightning-sparked fire outbreak that has rapidly evolved in northern California — even in the context of the extraordinary fires of recent years. It’s truly astonishing. By the time this post is published [on Friday], around 800,000 acres of land will have burned over the past 8 days in California — over 700,000 of which in the northern part of the state, and about 500,000 within 100 miles of San Francisco. For perspective: less than 250,000 acres burned in California in all of 2019. There are so many fires right now that multiple wildfires under 5,000 acres have gone largely unattended, and unmentioned in the media. CalFire stated earlier today that to fight these fires to the maximum of their ability, the agency would near nearly 10 times more firefighting resources than are available.

And, yes, as Intelligencer’s David Wallace-Wells has repeatedly pointed out, the intensifying perennial California wildfire crises are a climate-change story. Full stop.

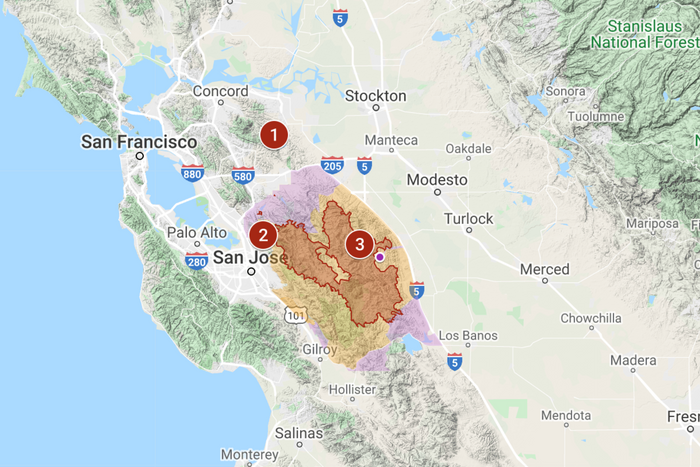

The most significant fires

The LNU Complex Fire

As of Monday, the LNU Complex Fire has burned more than 347,000 acres in Sonoma, Napa, Lake, Solano, and Yolo counties — making it the second largest fire in state history. It is just 21 percent contained, and has already consumed at least 871 structures and killed at least four people. Some 30,500 structures remain threatened by the complex, which comprises multiple individual fires, including the Hennessey, Gamble, Walbridge, Meyers, and Green fires. This is how fast it grew in less than a week:

On Friday, less than 600 firefighters had been assigned to the blaze. That then doubled to over 1,400 on Saturday, plus a total of 200 fire engines. The fire threatens the state’s most famous wine region, an area that has faced numerous wildfires in recent years, including the Kincade Fire in the fall of 2019, which burned more than 77,000 acres in Sonoma County and led to an evacuation of some 190,000 people.

SCU Complex Fire

As of Monday, the SCU Complex Fire, which is located east of Silicon Valley, had burned more than 344,000 acres across Santa Clara, Alameda, Contra Costa, San Joaquin, and Stanislaus counties — making it the third largest fire in state history. While it has mostly burned in rugged, sparsely populated areas, the fire was still only 10 percent contained on Sunday, and continues to threaten some 20,000 structures. The complex began as a group of about 20 smaller fires that later merged into two massive ones in the middle of last week. Its fast growth was due to the fact that it struck remote areas that hadn’t burned in years — meaning there was a surplus of easy fuel for the flames. Some 6,000 people have been forced to evacuate their homes because of the blaze.

CZU August Lightning Complex Fire

The third largest fire burning in Northern California is the CZU August Lightning Complex Fire, which has struck the Santa Cruz Mountains in San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties. As of Sunday, it has burned more than 71,000 acres and is only 8 percent contained, but its growth has slowed significantly after originally exploding in size in the middle of last week. It has already destroyed 115 structures, continues to threaten more than 24,000, and has prompted evacuations of at least 77,000 people from their homes, including in multiple small towns like Boulder Creek, Ben Lomond, and Scotts Valley, as wells as UC Santa Cruz. One reported death has been linked to the fire.

The CZU Complex began as a group of about 22 smaller fires that were started by lightning strikes on the morning of August 16 and later merged into one big fire. Though firefighters were able to take advantage of more favorable weather conditions over the weekend, earlier efforts were stymied by poor visibility — initially preventing the use of aircraft support, as well as limited access to the blaze and competition for firefighting resources, according to the Santa Cruz Sentinel. As of Sunday, nearly 1,350 firefighting personnel were working to contain the blaze.

These are only the three biggest fires. Several more continue to burn across the region as well:

The multifold pandemic problem: COVID-19 plus evacuations and wildfire smoke is a dangerous mix

All of this is happening in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, which makes it a compound nightmare for residents and public officials in the fire and smoke zones. While California has made substantive recent gains in slowing the spread of COVID-19 following a summer spike, the wildfire crisis could lead to more than just a setback. In addition to the logistical stress of the state fighting two crises at once, there are the complications of evacuating safely in the time of social distancing, plus the added dangers of hazardous air quality and the difficult-to-quantify mental-health toll.

Last week, the Los Angeles Times reported one Vacaville family’s struggle to cope with the dual crises:

Lloyd Broughton, 78, evacuated with little warning after a firetruck came up his road north of Vacaville at 3 a.m. Wednesday. Along with his wife, Anne, 73, and daughter Kristine, 35, they gathered their seven rescue cats and packed two cars.

“No one is ready for it,” he said of having to leave in the middle of a pandemic. All three were having breathing problems — Kristine has asthma, and her parents both use CPAP breathing machines. With a heavy layer of ash falling, they were already coughing and having trouble breathing, Kristine said.

Tonight they hope to go to a motel if they can’t return home. Though they aren’t too concerned about the coronavirus, Kristine said the shelter was not yet set up to screen for the contagion. “They just got in thermometers but are out of batteries,” she said.

The coronavirus has also complicated firefighting efforts, as the Sacramento Bee reports:

“They can’t put as many firefighters next to each other on the fire line,” said Bill Stewart, a UC Berkeley wildfire expert. “The pickup trucks (transporting crews) are historically full of people. Now they’re limited to one or two.”

Last month, the state said it expected to have about a dozen fewer inmate crews available for wildfire duty, partly because thousands of inmates have been released because of virus risks. The total inmate population is down 9% from a year ago, according to Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation data …

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said that no inmate crews are currently on COVID-19 lockdown, but the number of inmates are down significantly since last summer. In 2019, there were 2,800 inmate firefighters. This year, there are only 2,026.

One of the ways California has traditionally handled fire season is to deploy thousands of specially trained (and poorly paid) inmates to handle dangerous and important work like cutting fire lines. Early last month, 12 of California’s 43 inmate fire camps were placed on lockdown after an outbreak of COVID-19 at the prison where the fire crews are trained. The lockdowns subsequently ended. The state hired more firefighting personnel to replace the inmate firefighters it lost to early release, but it currently needs all the help it can get — and it has traditionally been very difficult for inmate firefighters to gain normal employment on fire crews after they are released from prison.

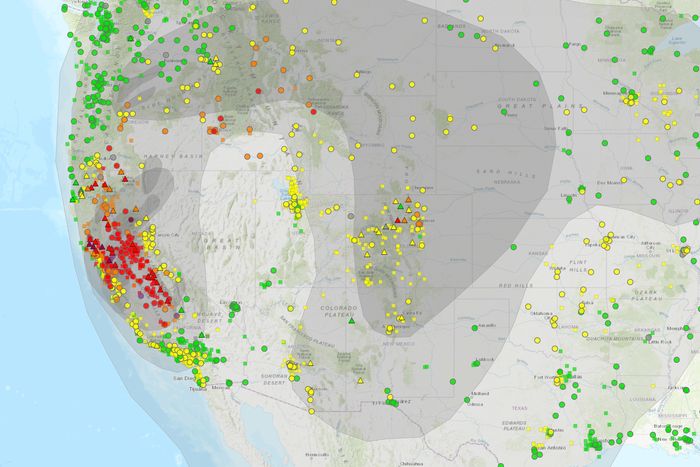

And then there is the significant air-quality issue, as the California wildfires have enveloped a wide swath of both the state and the western United States in smoke, leading to widespread air-quality warnings — particularly in the Bay Area — but also much, much further away. This piles one public-health crisis on top of another.

This map, from the SSEC, shows the smoke conditions as of Monday:

And this map, from the EPA’s AirNow program, shows smoke plume reach in addition to air-quality sensor readings (red and orange icons indicate poor air quality), also as of Monday:

Wildfire smoke irritates and inflames the lungs, greatly exacerbates respiratory illnesses, and can weaken a person’s immune system. In other words, the hazardous air quality may make it both easier to catch COVID-19 and develop a more severe infection, as one expert explained to CNBC last week:

“With the wildfires, we’re going to see increases in PM 2.5,” said Dr. Neeta Thakur, a pulmonology and critical physician at UC San Francisco, referring to fine particular matter. “There’s some studies that have suggested an association between increases in particulate matter and severity of Covid-19 infections,” she said. “Although how those are related is less well understood.”

The smoke also adds danger to the lives of California’s farmworkers. As the San Francisco Chronicle explained last week, many of those workers feel they have no choice but to continue to work, no matter what. But it’s far from clear whether or not they will all be able to do that safely, particularly since the N95 face masks that they would require are already in short supply.

Agricultural workers, who are considered essential workers, have already been at a higher risk for contracting the coronavirus, and many are undocumented, with little recourse if their employers do not supply them with the proper equipment or enforce safety protocols.

The other issue is that the natural reactions to smoke inhalation — coughing and sneezing — are also the most effective way to propel COVID-19 droplets into the environment and infect others. This problem could be particularly acute among firefighting personnel, who will not only be exposed to the most smoke, but are also likely to end up in situations of close contact.

It’s not clear what kind of testing is available, or required, for the fire crews who have rushed into action against the fires — or if it’s even possible those test results could be returned in time to provide any kind of effective screening. Will the tens of thousands of evacuees and 14,000 firefighters all have to quarantine themselves once the crisis is over? Will contact tracing be possible in the chaos?

Making matters worse, the vast majority of face coverings that Americans have hopefully begun to wear to protect themselves and others from the coronavirus aren’t effective protection from smoke inhalation. Unfortunately, N95 and KN95 respirators are the only face masks that can filter smoke particles enough to have an impact, and they have been difficult to find amid the pandemic, even for the health-care workers who need them the most. In addition, many of the consumer models feature unfiltered exhaust valves, and regardless, as an expert explained to the San Francisco Chronicle last week, the best way to avoid the danger of smoke-saturated air is to stay indoors:

“I see people jogging with an N95 mask, and they just don’t get it,” said Tom Dailey, chief of pulmonary medicine at Kaiser’s Santa Clara Medical Center. “It means 95% of the particles are kept out, but you’re still inhaling 5% of them. We want people to stay indoors. Do not exercise. The masks are for those who cannot avoid being out of doors.”

There is also a compounded mental-health risk of trying to juggle two life-threatening crises at the same time, let alone ones that require opposite reactions, as Jacob Stern highlighted at The Atlantic over the weekend:

Mental-health researchers have repeatedly found that a victim’s risk of post-disaster psychological trauma depends in large part on their history of mental-health problems. With each successive trauma, the risk heightens and the burden accumulates. “You can think of coping resources in part as a fixed entity, like a muscle,” says Joe Ruzek, a longtime PTSD researcher at Stanford University and Palo Alto University. “You have a certain amount of energy to deploy,” and at some point the amount required exceeds the amount available. That, at least in theory, is when resilience reaches its limit. For many people — especially health-care workers, COVID-19 patients, and those who have lost loved ones — the past six months have steadily depleted those energy stores. As a result, people may have more trouble than usual coping with the wildfires, which leave deep psychological scars even in ordinary years …

What makes the wildfire-pandemic combination uniquely devastating at both a societal and a personal level is that the two disasters demand opposite responses. A pandemic, as Americans have learned, requires people to stay home and practice social distancing. A wildfire, by contrast, requires them to evacuate and congregate. The director of California’s Office of Emergency Services has acknowledged the need for an evacuation plan tailored to the pandemic, and the state’s new rules provide for prepackaged meals, health screenings, and the conversion of hotels, campgrounds, and college dorms into shelters. Still, for most people, following one safety protocol will mean compromising on others. Hence the Californian’s dilemma: Those who flee risk infection; those who stay risk incineration. Something has to give.

Also at The Atlantic, in a chilling piece pondering California’s post-pandemic, climate change–baked future, political scientist Leah C. Stokes made another important point:

Those theoretically “safe” in their homes don’t have it easy, either. Without electricity [thanks to the recent rolling, heat-wave related blackouts], many Californians have to choose between opening the windows and breathing in air choked with smoke, or keeping them closed in a hot house. My friend posted a picture of herself wearing an N95 mask with an exhalation valve, and a surgical mask on top: the first to protect herself against the smoke, the second to protect others from the virus.

I don’t want to live in a world where we have to decide which mask to wear for which disaster, but this is the world we are making. And we’ve only started to alter the climate. Imagine what it will be like when we’ve doubled or tripled the warming, as we are on track to do.

And then there are the ancient redwoods

California’s oldest existing state park, Big Basin, which has been known for its ancient coast redwoods for almost 120 years, suffered extensive damage from the CZU August Lightning Complex Fire on Wednesday. The park’s historic headquarters, which was built by Civilian Conservation Corps crews in the 1930s, was reduced to ash, as were multiple other structures in the park — and an unknown number of the park’s magnificent redwoods were damaged, some fatally.

A pair of journalists from the Mercury News hiked in on Thursday to get a sense of the damage:

They found scattered among the tall trees some fallen giants. One, found just before the headquarters and with a base more than a dozen feet across, had burned and shattered, sending the massive trunk crashing to the ground, where it lay in a deathbed of ash and blackened undergrowth. Other redwoods still upright were burning at the base, fire eating up inside their trunks, and these trees seemed doomed to fall. Nearly all Big Basin’s iconic redwood trees were scorched, and while many escaped the blaze with foliage intact, dozens near the park center had been torched up to the crown and their tops had burned off or broken.

Meanwhile, more ancient redwoods remain threatened in the Armstrong reserve in Sonoma County, the San Francisco Chronicle reports:

In the North Bay, the fast-moving LNU Lightning Complex burned into the Austin Creek State Recreation Area and looked ready Friday to engulf the Armstrong reserve. The 805-acre grove, which features the 1,400-year-old Colonel Armstrong Tree and the 310-foot-tall Parson Jones Tree, was facing possible destruction because fire officials decided Thursday they did not have enough resources to protect it while also saving people’s lives and property.

On Saturday, Cal Fire said that so far, old-growth redwoods in the reserve had been spared from the Walbridge Fire, which is part of the LNU Complex, but the upper section of the reserve had been hit.

The good news is that redwoods have evolved to protect themselves from these events, up to a point, as a fire ecologist explained to the Santa Cruz Sentinel:

Kristen Shive, a fire ecologist and director of science at Save the Redwoods League, said that redwood bark is up to a foot thick and resists fires, which is why, in part, the trees live so long. However, if fires burn hot enough, they can damage the cambium, the layer of material under the bark, which transports water and nutrients.

“An active crown fire could kill trees,” she said. “But in many cases, they will look pretty sickly and sad for a while, but they can eventually recover. We should be concerned, but we can have cautious optimism that some of these big giants have made it.”

The old-growth trees are the least likely to suffer fatal damage. Other, younger trees have already been less fortunate: