The Manhattan district attorney’s office announced today it was investigating “public reports of possibly extensive and protracted criminal conduct at the Trump Organization.” The office had previously been thought to be focusing on a potential campaign-finance violation from Trump’s giving hush-money payments to alleged former lovers. In a sane world — a world we left behind long ago — the news that the president of the United States was facing a probe for a wicked array of alleged crimes would be a world-shattering revelation. In the world in which we reside, it may or may not register in the news cycle.

Why aren’t more people freaking out over this news? One reason is that the simultaneous public-health and economic crises have blotted out everything else. Another reason is that the anticlimactic end to the Mueller investigation and impeachment left a residue of shared belief that Trump is immune to any prosecutorial threat.

But the Mueller probe fizzled out in large part because of Mueller’s choices. As Jeffrey Toobin documents, Mueller limited his investigation to criminal charges that were already being pursued by the Department of Justice. He made a series of conservative choices that allowed Trump to stymie the investigation by refusing to testify and by persuading his most exposed aides, like Roger Stone and Paul Manafort, to withhold cooperation.

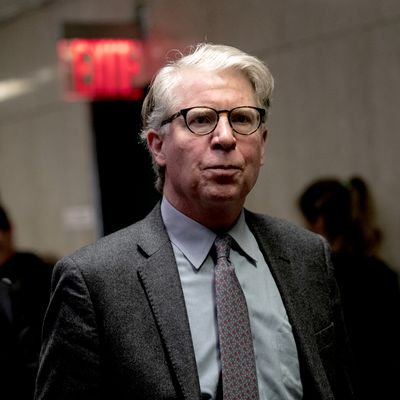

Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance may not be so constrained. Vance is trying to obtain Trump financial records that could confirm publicly reported crimes. There are potentially a lot of them. A New York Times investigation two years ago found a trail of phony records used in what the newspaper described as clear fraud. Trump has reportedly collected phony hurricane damages. ProPublica has uncovered massive discrepancies between the figures Trump has given to lenders and the government, portraying himself as rich to the banks and poor to the government, thus defrauding either one or both.

There are obviously worrisome political ramifications to a high-profile criminal investigation of a presidential candidate like Trump. It would be terrible if state prosecutors began to routinely insert themselves into presidential campaigns by pursuing high-profile allegations against opposing-party nominees. The system needs safeguards to prevent prosecutorial abuse from dominating the campaign (the way the FBI’s ultimately empty probe of Hillary Clinton’s emails likely decided the 2016 election).

Yet the system also needs guardrails to prevent, or at least inhibit, the election of an outright crook. Trump defeated all the constraints. He defeated the most common mechanism, the norm requiring candidates to disclose their financial information, by simply refusing until reporters stopped bringing it up. He evaded prosecution by fighting subpoenas all the way to the Supreme Court, dragging out the process for years.

Now Vance is racing to beat the election deadline because of Trump’s dilatory tactics, putting himself in the position of either dropping a potential indictment shortly before the election or allowing Trump’s conduct to escape any public accountability for both of his elections.

In general, politics should not be criminalized. But if the president is a career criminal, lots of normal principles fall by the wayside.