Climate change is making the world unsafe for capitalism. In the face of the “frequent and devastating shocks” wrought by unabated warming, the “fundamental conditions supporting our financial system” could prove impossible to sustain. Finance will struggle to perform its risk-management function if entire coastal regions become uninsurable. Banks won’t supply America’s breadbasket much credit if droughts routinely desiccate its crops. Already, private investors are failing to price assets in a manner consistent with ecological reality. Only a combination of carbon taxes that internalize dirty energy’s true social costs — and speed the development of renewables — can mitigate the physical and financial risks that lie ahead of us. Therefore, the U.S. government must aggressively intervene in energy markets while ensuring that the burden of a green transition “does not fall on low-to-moderate income households” or “historically marginalized communities,” posthaste.

This analysis does not come courtesy of Greenpeace, the Sunrise Movement, or some eggheads at the United Nations. Rather, it is a rough summary of a report commissioned by the (Trump-appointed) Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) — and written by analysts from Morgan Stanley, S&P Global, Vanguard, BP, ConocoPhillips, and Cargill — in collaboration with academics and environmentalists. (Some of those firms issued statements stipulating that they don’t necessarily endorse the report’s every particular, only its broad strokes.)

Released Wednesday morning, the report echoes the conventional wisdom among financial observers in less climate-science-averse corners of Western capitalism. Five years ago, Mark Carney, then governor of the Bank of England, warned that the planet’s warming presented three systemic risks to the global financial system: that catastrophic losses would tank the (heavily financialized) insurance industry and take financial markets down with it; that liability lawsuits from victims of climate change could suddenly erase the value of dirty-energy firms; and that failure to orchestrate a steady transition to renewables would result in a sudden and belated abandonment of trillions of dollars’ worth of fossil-fuel assets.

Last year, the economic historian Adam Tooze wrote about risk No. 3 in some detail:

Assuming no spectacular breakthrough in carbon capture, if we are to stabilize temperatures below catastrophic levels, the vast majority of the world’s known fossil fuel reserves will have to stay in the ground.

Leaving that energy untapped will mean as much as $28 trillion in lost revenue for oil, gas, and coal companies over the next 20 years. And that matters for the financial system because investors already own bonds and shares connected to those assets … If financial markets have time to adjust, even such huge losses could be absorbed. But if the changes strike lenders and investors suddenly and unexpectedly, they risk triggering … a financial heart attack, a crippling blow to bank balance sheets that radiates, as we saw in 2008, to the entire economy. In the subprime mortgage sector, which was worth around $1 trillion, losses ran to a few hundred billion dollars. The carbon bubble is far larger.

On Wednesday, the Republican CFTC chairman Heath Tarbert discounted some of his own commission’s ideologically inconvenient findings by noting, in an interview with the New York Times, “The subcommittee’s report acknowledges that ‘transition risks’ of a green economy could be just as disruptive to our financial system as the possible physical manifestations of climate change, and that moving too fast, too soon could be just as disorderly as doing too little, too late.”

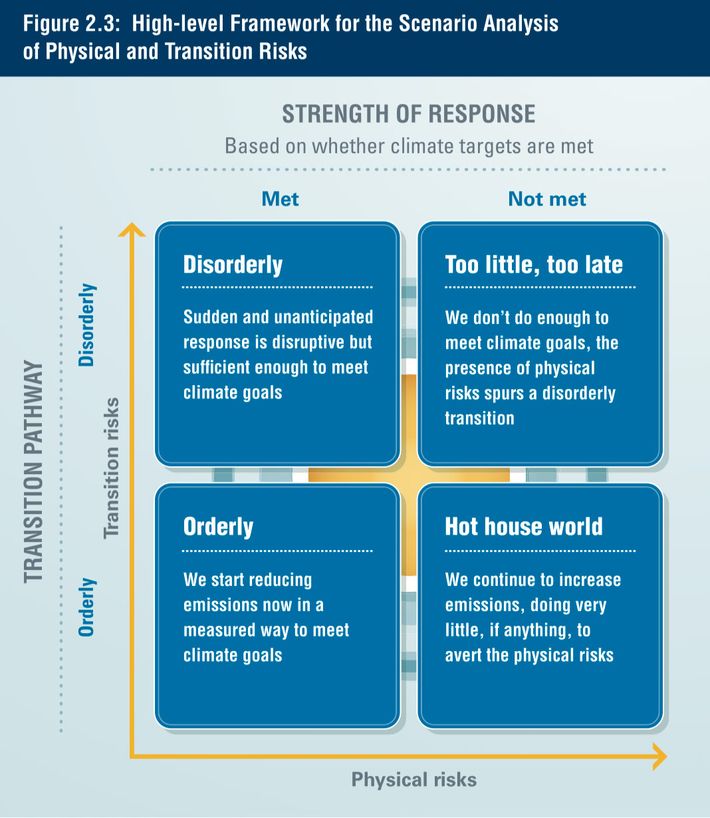

But this is a misreading of the report. Transitioning “too fast” does present a financial risk — bringing the value of all untapped fossil-fuel assets down to zero tomorrow would sow financial chaos. But there is no such thing as transitioning “too soon.” As the CFTC’s own graphic illustrates, the sooner America imposes a carbon tax, and other reforms aimed at moving capital away from oil and toward renewables, the more gradual and orderly the energy transition will be.

Tarbert’s error is blatant but understandable. After all, his commission’s findings can only be reconciled with his president’s agenda if they are willfully misinterpreted. Donald Trump has done virtually everything in his power to increase carbon emissions and further externalize the social costs of dirty energy. In interviews with the Times, the authors of the CFTC’s report “acknowledged that if Mr. Trump is re-elected, his administration is all but certain to ignore the report and its recommendations.” Which is to say financial analysts from some of the world’s most powerful corporations apparently see the reelection of a Republican president as a threat to the long-term stability of global capitalism.

Meanwhile, Wall Street’s largest banks reassured their clients this week that congressional Republicans will eventually acquiesce to another hefty stimulus package (as opposed to the “skinny” one that the party currently backs), with Morgan Stanley projecting a “a $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion package” by month’s end. At present, Mitch McConnell & Co. have refused to meet Nancy Pelosi’s caucus halfway on relief funding. This is in part because Republicans oppose significant fiscal aid for states and cities, a policy that enjoys the support of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Moody’s Analytics, which has argued that “every state needs additional federal aid” and that the “economic impacts” of states “not receiving it quickly are exceedingly high.”

These developments testify to an underappreciated fact about contemporary American politics: Contrary to popular conception, the GOP does not govern in the interests of U.S. business — or, at least, not in the long-term interests of U.S. business as a whole.

To be sure, Trump has done a great deal to benefit corporate America’s incumbent executives, especially those looking to maximize their own wealth in the run-up to retirement. Through his regressive-tax cuts and deregulatory measures, the president has saved major U.S. firms and their shareholders a bundle. The nation’s six largest banks alone have pocketed $32 billion as a consequence of Trump’s policies. And for America’s most socially irresponsible enterprises, this administration has been a true godsend. Since taking power, the Trump White House has, among other things, expanded the liberty of coal companies to dump mining waste in streams, pushed to preserve the rights of retirement advisers to gamble with their clients’ money, freed employers from the burden of logging all workplace injuries, and ended discrimination against serial labor-law violators in the bidding process for government contracts.

But the Republican Party is too corrupted by rentier and extractive industries — and too besotted with conservative economic orthodoxy — to advance the long-term best interests of American capital.

This reality has made itself conspicuous at various points over the past two decades. During the 2008 crisis, George W. Bush’s efforts to stabilize the U.S. financial system encountered sustained opposition from his party’s House caucus, relying on strong Democratic support to make it into law. Over the ensuing years, the tea party’s debt-ceiling demagoguery repeatedly threatened to force the country into a needless debt default. Under Trump’s leadership, meanwhile, the GOP dismantled much of the pandemic management infrastructure that its Democratic predecessor had built up in response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Once COVID-19 arrived, the president proceeded to misleadingly downplay the threat of the virus; discourage his supporters from complying with recommended measures for containing its spread; refused to coordinate a comprehensive federal response, opting instead to let blue states bid against each other for limited supplies; convened potential super-spreader events in viral hot spots; publicly admitted that he hoped to suppress testing so as to make case counts look more favorable than they actually were; advised Americans that injecting disinfectant into their lungs might cure COVID; and blocked fiscal aid to states and cities amid a broader effort to coerce them into reopening their economies before the virus was contained.

It is impossible to say precisely how many of the 190,000 U.S. COVID deaths — or how much of the pandemic’s estimated $8 trillion domestic economic toll — would have been averted, were it not for the Trump GOP’s exceptionally irresponsible management of public health. But we do know this: Despite the fact that America’s population is younger than the European Union’s — and thus at lesser collective risk to COVID-19 — our per capita death rate is more than twice as high: If our COVID death-to-population ratio was the same as the E.U.’s, 106,000 fewer Americans would have perished from the disease.

Thus, it is not necessarily in the immediate interest of U.S. business writ large to have a solipsistic con man in charge of the federal government, no matter how much he helps individual firms loot the public purse or skirt regulatory compliance. To the contrary, it is at least conceivable that, had the U.S. presidency not been held by an ideological movement contemptuous of the very concept of public health in 2020, American businesses would have been trillions of dollars more profitable in the coming decades than they are now poised to be.

Contra ruling-class reactionaries’ self-flattering dogmas, private enterprise is — and always has been — reliant on competent statecraft. Conservatives recognize capital’s reliance on “big government” in the realm of military defense. But in the Anthropocene, emergent diseases and climate change pose at least as large a threat to capital accumulation as any hostile foreign power. Meanwhile, in a globalized economy beset by chronic shortfalls of demand and periodic financial shocks, the GOP’s resilient skepticism about economic stimulus renders the party an uncertain friend to corporate America in its times of need. Granted, the party has largely fulfilled its duty to reflate asset prices and shore up credit markets this year. But the strength of the recovery (such as it is) is at least partly attributable to policies that originated with Democrats, and which the GOP accepted only grudgingly in March and has since refused to renew. As is, there is every reason to think that American businesses (especially small ones) would be better off if Pelosi’s caucus could set fiscal policy by fiat.

None of this is to suggest the Democratic Party reliably advances the enlightened interests of American business. In the recent past, Democratic administrations have been led astray by many of the same stale premises that presently shape GOP orthodoxy. Bill Clinton’s deregulation of finance and budget balancing lay the groundwork for a financial crisis that the U.S. economy never fully recovered from. Barack Obama’s fear of deficits (or, at least, deficit politics) led his party to pursue a grossly inadequate fiscal response to the Great Recession. Separately, Democrats are more accountable to labor, environmentalists, and other economic stakeholders whose interests are in some tension with the imperative of profit maximization, even on a long time horizon.

Nevertheless, if one accepts the reality of climate science — and the analysis of Trump’s own CFTC — it is clear that the Democratic Party is the most capable steward of American capitalism on offer. The GOP may be a more indulgent guardian. It may spoil its favorite industries rotten with gifts and permissiveness. But spare the state capacity and you’ll spoil the corporate sector. Trump may not give fossil-fuel companies a hard time for despoiling the planet, but someday they’re going to learn that — out in the real world — such misbehavior has consequences.