Years from now, when we look back at the coronavirus pandemic, it is very possible that the most damaging element we will identify is its catastrophic effect upon public education. The devastation will be social and economic, permanently degrading the skill base of the workforce and robbing a generation of children, especially low-income students, of any chance to enter the middle class. And the question we will have to ask is whether the tragedy was truly necessary.

Begin with the effect on the workforce brought about by eliminating the largest source of free childcare. With millions of children now required to learn remotely, their parents now have to stay home all day. A million married women left the workforce over the last month. Indeed, even as jobs have slowly recovered from the depths of spring, single people have accounted for more than 100 percent of all job gains. Joblessness and poverty leave trails of physical and emotional hardship for decades; the current recession is to a significant degree a crisis of unschooling.

The damage to the future workforce will be far worse. Students denied in-person education will suffer permanent learning loss that will degrade their skills for decades to come. One estimate by the OECD roughly pegs the long-term cost in foregone productivity to the United States at around $15 trillion. That number is obviously speculative, but it provides some sense of the economic scale of the calamity.

The social damage will not be spread evenly. The undeveloped mental potential and stunted careers will be concentrated disproportionately among low-income and minority students. One survey found four-fifths of Hispanic students, three-quarters of Black students, but only half of white students lack access to in-person learning. Affluent parents have the means to cushion the blow to their children: by working from home, having one parent quit work, forming learning pods, hiring tutors, or enrolling in private schools, which are reopening for in-person learning much faster.

Primary education has been functionally privatized on a mass scale. The sink-or-swim result has been predictable. Families with the resources to absorb the withdrawal of public services have kept their childrens’ heads above water, and those who have not have been left to drown. My two children, both enrolled in public schools that have gone remote since the pandemic began, have lost a fair amount of learning, but benefitted from an array of privileges: My wife and I both have white-collar jobs we can do at home, and can provide the (fortunately occasional) assistance high-schoolers require. We found one a spare laptop computer last spring, enrolled them in extra online learning to supplement the shortfall in their classes, are able to help with curriculum questions, and have never relied on free school meals to feed them. The result is worse, but surmountable.

A portrait of what remote learning looks like for children who have none of these advantages can be seen in Alec MacGillis’s heartbreaking narrative about remote education in Baltimore. McGillis begins with the story of a promising low-income student he has been tutoring, whose impoverished life has made remote learning all but useless. He lacks the stable home base, attentive caregiving, nutrition, and access to technology that are the baseline requirements for remote schooling to work at all. Like many low-income kids, his education since March has been almost indistinguishable from dropping out.

The tragedy is that the choice to close so many schools was hardly cut-and-dried. The scientific understanding of the novel coronavirus has been in constant flux. In-person education clearly creates some risk. How much risk is unclear. Some of the best-credentialed public-health experts maintain, and have maintained for months, that the health risk of in-person school is manageable. For the most part, their advice has been spurned, and states and cities have erred on the side of caution.

There are several reasons why. The coronavirus response on a national level has been very poor. The federal government has failed to finance as much protective equipment and infrastructure upgrades (for better air circulation, for instance) than it should have. And, as MacGillis notes, Trump’s high-profile intervention drove up opposition to school opening. As soon as the president demanded schools open their doors, opposition to the idea shot up 20 points as Americans understandably concluded that he was pursuing his own political interest at the expense of public health. But this turns out to be one of the cases where the normally reliable heuristic, everything Trump wants is bad, has failed.

A factor in the debacle that deserves more attention than MacGillis was able to devote to it is the role of the teachers unions. Trump’s toxic intervention enabled the unions to polarize the debate, and drive progressives toward their uncompromising stance against school reopenings.

Union concerns about safety were not wholly unfounded — the science, again, remains in flux. The key point is that the union’s incentives are misaligned with those of their students. For kids and families, in-person education presents a trade-off between the health risks of going to school, and the economic and social costs of staying home. For younger low-income students, the costs of losing in-person school are catastrophic and permanent. Teachers, on the other hand, are incentivized almost entirely to minimize health risks. They get paid the same salary if they go to school or teach from home. They might feel unhappy about watching their students flail, but they do not have anything like the investment that the families have.

Teachers unions have been an influential force against reopening schools even in cities and states where elected officials felt it could be done with reasonable safety. After Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot proposed a hybrid in-person learning plan, the Chicago Teachers Union threatened a strike, and then claimed victory when she backed down and agreed to retain online-only learning. Teachers unions in Florida, California, and elsewhere have sued to block in-person instruction. In Detroit, union activists “stood outside one of the district’s bus terminals beginning at 5 a.m., blocking buses from leaving to pick up students to take them to school.” The Los Angeles teachers union insisted “going back to normal is not an option,” and packaged their opposition to reopening with a host of other demands, including police-free schools and a moratorium on new charters.

This summer, American Federation of Teachers president Randi Weingarten threatened “safety strikes” against reopening. More radical activists have vowed to “double down” with “transformative” demands.

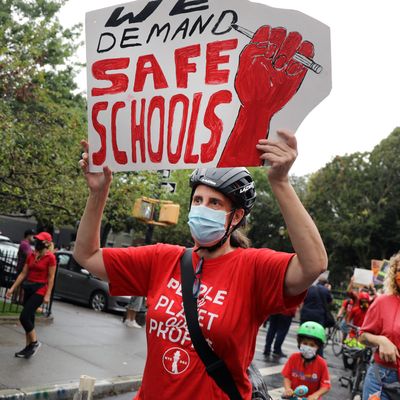

The language and the logic of the pro-closing activism has treated the scientific case against in-person learning as a hardened fact. New York’s rally against in-person learning used the slogan #wewillnotdiefordoe, as if the school bureaucracy, and not its children, were the only opposing consideration.

In his reporting, MacGillis interviewed Weingarten, who cited outdated research to support her hardline stance:

Weingarten said that this came down to “trust.” “If parents and teachers aren’t confident that the safety measures are in place, then you’re not going to be able to stand it up in the middle of a pandemic,” she said. Contending that the virus was more harmful to kids than first realized, she cited the South Korean data — she was not aware of the revision, she said — and then another recent Times story on cases rising among kids, which had also been challenged for lacking context and scale. I noted the disagreements with her citations. She replied, “In the absence of trusted information, people have fear right now.”

Note how, after being told her facts were incorrect, Weingarten retreated to perception: “people have fear right now,” and so the fear, not evidence, must guide policy. That fear just happens to line up with the interests of her constituency, of course.

Launching off the premise that science is clear that schools must remain shut, unions have treated pushes to reopen them as motivated either by Trump’s political needs or bureaucratic indifference to public health. In Washington, D.C., teachers demonstrated with “body bags” — trash bags stuffed to resemble corpses — to protest reopening. When the school system polled members to ask about their health needs and willingness to resume in-person instruction, the union told them not to cooperate with the survey. The resistance succeeded: This week, D.C. public schools announced it would partially reopen elementary schools, rotating students in, because not enough teachers had indicated availability to resume full-time in-person instruction.

D.C.’s two largest charter networks, KIPP and Friendship, resumed in-person instruction even as the neighborhood schools remained closed. (KIPP is offering teachers a $175 per-day bonus for in-person teaching.) Both networks serve overwhelmingly non-white, non-affluent students in low-income neighborhoods, students who are able to escape the disaster of remote education because their teachers do not belong to a union actively resisting in-person education.

D.C.’s case is hardly anomalous. One survey found parents of children in private or charter schools were 50 percent more likely to say they were “very satisfied” with their children’s schooling during quarantine, and also lower levels of reported learning loss. Politics, far more than science, shaped school district decision-making,” finds a new study by political scientists Michael Hartney and Leslie Finger, “Mass partisanship and teacher union strength best explain how school boards approached reopening.

In Washington, like many other places, restaurants and bars are open even as the schools are closed. This bizarre combination reflects the balance of political pressure, not any logical interpretation of public health. Business owners want to reopen because it is in their interest to do so. Teachers want to remain closed for the same reason. Both groups have perfectly compelling and sympathetic reasons. It’s not easy to tell somebody who spent years building a business to let it fail, or to force a teacher to run even the small risk of contracting a terrifying illness for the benefit of somebody else’s child.

And yet following the interests of the most powerful organized constituencies has produced a result that, on the aggregate, is irrational. The damage we are incurring now will haunt us for generations.