On the very day that the U.S. Senate confirmed a new Supreme Court Justice nominated by a president who explicitly hopes she will help decide an election outcome he has for months signaled he might contest, the first two justices he placed on the Court offered an alarming glimpse into the activist role they believe they should play in disputes over state election laws.

The actual holding in the Supreme Court’s order in Democratic National Committee v. Wisconsin State Legislature, as explained by Chief Justice John Roberts, was entirely predictable and not terribly controversial: relying on the same principle it applied in earlier cases involving the Wisconsin primary and general election rules in Alabama and South Carolina, the Court swept aside a district judge’s ruling liberalizing the deadline for mail-ballot receipt on grounds that federal courts should not intervene in state election-law disputes too close to the elections they govern, particularly when second-guessing state legislatures and state courts. Roberts’s terse opinion in the Wisconsin case explicitly distinguished it from a recent Pennsylvania case in which the Court declined (on a 4-4 tie vote) to overturn a State Supreme Court decision that similarly delayed mail-ballot receipt deadlines on grounds of slow mail delivery and COVID-19-prompted fears of voting in person.

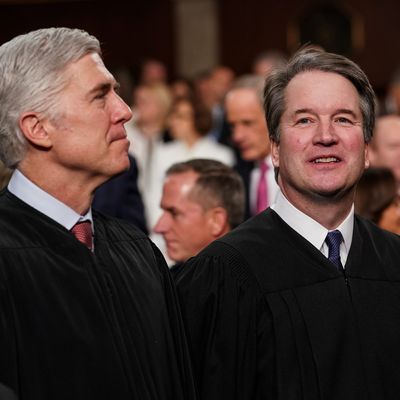

But Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, who indicated they would have overruled the state court in the Pennsylvania case, have now in separate concurrences made their position on state election disputes reasonably clear in a way that should alarm anyone worried about a contested election in this and any other presidential contest. Both justices embrace an “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution’s endowment of state legislatures with exclusive powers in presidential elections, defending SCOTUS’s right to smack down state as well as federal courts who interfere with it.

Gorsuch was very explicit about this principle, as Vox’s Ian Millhiser explains:

As the Court held most recently in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), the word “legislature” should be read “in accordance with the State’s prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the Governor’s veto.”

But Gorsuch’s opinion suggests that this longstanding rule may soon be gone (again, as he put it, “state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules”). State supreme courts may lose their power to enforce state constitutions that protect voting rights. State governors may lose their power to veto election laws, which would be a truly astonishing development when you consider that every state needs to draw new legislative maps in 2021, and many states have Republican legislatures and Democratic governors.

More immediately, if there are disputes over the election results in this presidential election, Gorsuch would presumably uphold state legislative prerogatives against all contenders. As it happens, Republicans currently control legislatures (though not necessarily the governorship or state courts) in virtually every 2020 battleground state. While his opinion does not specifically refer to the disputed theory that legislatures have the unilateral power to appoint presidential electors even if federal or state laws provide otherwise, it certainly points in that direction.

For his part, Kavanaugh adds two disturbing thoughts to the common theme of SCOTUS defending state legislative prerogatives in election disputes. First, he treats the need for firm deadlines on voting as having constitutional significance in language that is reminiscent of Trump’s ranting tweets about mail-in ballots overturning Election Night results. Kavanaugh wrote in his concurring opinion:

Those States want to avoid the chaos and suspicions of impropriety that can ensue if thousands of absentee ballots flow in after election day and potentially flip the results of an election. And those States also want to be able to definitively announce the results of the election on election night, or as soon as possible thereafter.

Second, as Politico’s Josh Gerstein notes, Kavanaugh also “quoted a prominent law professor’s caution that allowing the election to drag out could fuel claims of foul play.” And the president quickly echoed these arguments in a tweet minutes after the ruling came out:

[J]ust about 10 minutes after the justices issued their decision in the Wisconsin dispute, Trump tweeted out his latest warning that any results that come in after election night should be considered illegitimate. “Big problems and discrepancies with Mail In Ballots all over the USA,” Trump wrote, without offering evidence for his assertion. “Must have final total on November 3rd.” (Twitter labeled the post “disputed,” saying it “might be misleading about how to participate in an election or another civic process.”)

In a dissent to the order, Justice Elena Kagan responded to Kavanaugh’s ode to deadlines: “There are no results to ‘flip’ until all valid votes are counted. And nothing could be more ‘suspicio[us]’ or ‘improp[er]’ than refusing to tally votes once the clock strikes 12 on election night.”

In a footnote, Kavanaugh raised even more hackles by citing as wise precedent a radical minority concurring opinion in the most controversial election law decision of all, Bush v. Gore. The majority opinion in that case, which rewarded the presidency to George W. Bush by stopping a state-court-ordered recount in Florida, explicitly warned the decision was a one-of-a-kind emergency intervention that should not be used as precedent. But then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist penned a concurrence that argued SCOTUS had the constitutional obligation to stop courts at any level from interfering with the power of state legislatures in presidential elections. Presumably Rehnquist would have smiled on the Republican-controlled Florida legislature’s plans to directly appoint presidential electors had the Court not intervened to stop the recount.

One of the justices who signed onto Rehnquist’s concurrence, Clarence Thomas, is still on the Court. Another was Antonin Scalia, mentor to the new Justice Barrett.

We don’t really know if Gorsuch and Kavanaugh are consciously laying the groundwork to help Trump contest a loss to Joe Biden any more than we know whether Trump’s threats to steal the election are bluster or a real warning. But in my own writing about the “red mirage” scenario in which Trump would claim victory on Election Night based on heavy Republican in-person voting and then fight like hell to stop mail-in ballots from being counted, it was never completely clear to me how Trump could convince the world his claims of mail-in ballot fraud were credible, or how he could turn a muddied result into victory. Now we have one Supreme Court justice identifying with Trump’s alleged horror of post-Election Night uncertainty, and two Supreme Court justices pointing the way to a state legislative hijacking of the results. Both owe their lifetime appointments to the incumbent president. Their new colleague has refused to recuse herself from 2020 election disputes.

It would be the appropriately horrific end to this nightmare of a year if Trump’s three justices help him intimidate and lie and finagle his way to a second term. Maybe none of this will actually happen, but only a decisive Election Night victory for Biden would dispel the specters for good.