In January 2008, Barack Obama declared his intention to be the next Ronald Reagan. The Democratic presidential candidate told the Reno Gazette-Journal that Reagan had “changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not, and a way that Bill Clinton did not,” in that the Gipper had durably realigned bipartisan common sense about the role of government in the U.S. economy. Obama suggested that he wished to affect an equal but opposite paradigm shift.

It’s early (and admittedly, a bit trollish) to say but — it is possible that Donald Trump came closer to fulfilling Obama’s ambition than the former president himself did.

Last week Congress passed a $900 billion COVID relief package, which the Republican president opposed – on the grounds that its unconditional cash welfare payments should have been worth $2,000 per individual instead of $600 (and that the United States should not have a foreign aid budget). But on Sunday night, after procrastinating long enough to cost millions of jobless Americans an unemployment check, Trump finally signed the bill into law.

Combined with the CARES Act’s $1.8 trillion of fiscal aid, the new legislation brings the total amount of stimulus enacted in response to the COVID-19 crisis to $2.7 trillion. And Joe Biden — a consummate centrist Democrat and onetime deficit hawk — wants more, telling the Washington Post that he sees this week’s stimulus as a “down payment” on a broader package to come.

Which is remarkable, when one considers what the politics of stimulus were like the last time Joe Biden was in the White House. When the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passed in 2009, America’s official unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent. Average household wealth in the U.S. had just plunged. The global financial system had gone shaky at the knees. Meanwhile, America’s national debt was $9 trillion, or roughly 60 percent of GDP. And with Democrats in control of the presidency, Senate, and House, Congress opted to pass a grand total of $787 billion of stimulus. Within two years, even as unemployment sat near double digits, Washington pivoted to deficit reduction.

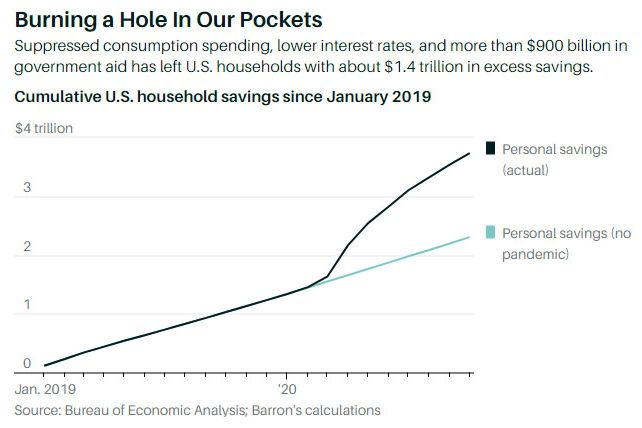

This week, America’s unemployment rate sits at 6.7 percent. Thanks to the CARES Act’s relief checks, the Fed’s interest-rate cuts and support for markets, and this year’s COVID-induced contraction on consumption opportunities, most U.S. households are better off financially now than they were before the pandemic. The global financial system is stable, and stock values are near all-time highs. Meanwhile, America’s national debt is $27 trillion, which is more than 100 percent of GDP. And with a lame-duck Republican in the White House and a GOP-controlled Senate, Congress agreed to pump $900 billion more into the economy.

Of course, there are several other, massive distinctions between this year’s recession and 2009’s. Three thousand Americans weren’t dying each day from a pandemic disease 11 years ago. The world-historic scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the way it sidelined entire economic sectors, make it a categorically different emergency from the Great Financial Crisis. This reality — combined with the fact that the COVID crisis happened to arrive in a year when a Republican president was up for reelection — might seem sufficient to explain why a GOP Congress was willing to condone the CARES Act’s generous fiscal provisions.

But I think there’s more to it than that. For one thing, by injecting another $900 billion into the economy now— at a time when average disposable income in the U.S. is exceptionally high — Senate Republicans effectively set Joe Biden up to preside over a robust recovery when (and if) the U.S. achieves herd immunity through vaccination.

The fact that the typical American worker — who did not lose her job during the pandemic but did receive an unexpected $1,200 from the government — is actually in solid financial shape should not blind anyone to the utter financial devastation that is being needlessly visited upon tens of millions of less fortunate Americans. Nor should it obscure the holes that the pandemic has left in many state and city budgets and the implications that will have for social services and public transit absent further federal aid. The $900 billion stimulus is criminally insufficient to the scale of our nation’s mass suffering and fiscal woes. But in strictly macroeconomic terms — which is to say, in terms of whether there will be enough demand in the economy to fuel strong (if grossly inequitable) growth next year — the stimulus may be larger than necessary: The GOP donor class did not need U.S. households to get another $600 from the government in order to see their portfolios appreciate in 2021.

The fact that congressional Republicans supported stimulus anyway likely reflects the financial desperation of small-business owners, a powerful constituency within their coalition, as well as a calculation that failure to pass stimulus will undermine their incumbent senators in the Georgia runoff elections. But I believe that it is also indicative of deficit hawks’ declining ideological power — which the first three years of the Trump presidency did much to erode.

The year before Trump came into office, mainstream economists both liberal and conservative believed that the U.S. economy was near full employment — which is to say, the lowest level of unemployment that the country could afford without triggering inflation. Therefore, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in 2015, and no “serious” policy wonks dared to argue that the U.S. should run massive fiscal deficits to stimulate demand and bring unemployment below 4 percent.

Then Republicans came to power — and, despite Paul Ryan’s best efforts, found themselves incapable of gutting Medicaid. The GOP had hoped to slash more than $1 trillion off federal spending on health care for the poor and use these savings to defray the costs of a giant tax cut for the rich. But they weren’t going to let the failure of the former spoil the latter. Meanwhile, in order to pass the party’s desired increases to the Pentagon budget, Republicans were forced to acquiesce to increases in domestic spending. Put these two together, and the GOP effectively passed a large fiscal stimulus at the peak of an expansion — or rather, what center-left economists mistakenly believed to be the peak.

The deficit swelled to $984 billion in 2019, an extraordinary sum for a non-recessionary environment. This surge in demand helped push the unemployment rate down below 4 percent. And yet inflation remained too low, even as America’s most disadvantaged workers got a foothold in the labor market and a bit of growth in their paychecks. If Trump had had his way, his stimulative policies would have been dampened by giant cuts to social spending. But if true Trumponomics has never been tried, the actually existing variety proved largely successful. And this left an impression on some conservative wonks like Oren Cass, the former policy director to Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign, who recently wrote that the Trump economy’s strength was largely attributable to loose monetary and fiscal policy — and thus, going forward, “tolerance for policies that benefit workers while risking inflation should increase.”

On the center left, meanwhile, a sea change in orthodoxy about deficits was already under way. In 2019, Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist of the IMF, authored a paper arguing that nations should not make a priority of deficit reduction, so long as the interest rate they can borrow at is comfortably below their rate of GDP growth. Which is to say: If your capacity to service debt is growing faster than your debt, then your debt is not a problem. Given the Federal Reserve’s ability to set the interest rate on Treasury bonds at roughly zero — and still find buyers for U.S. debt — Blanchard’s argument suggested that America could well afford its obligations. This year, Jason Furman and Larry Summers — two quintessential Establishment Democrat economists — declared their rejection of “traditional ideas of a cyclically balanced budget on the grounds that it would likely lead to inadequate growth and excessive financial instability.”

Of course, shifts in common sense among policy intellectuals do not always translate into shifts in public policy. But the COVID-19 pandemic subsequently forced Congress to confront just how much fiscal capacity the U.S. government actually has — and what it can achieve by using it.

With its $600-a-week federal unemployment benefit and $1,200 relief checks, the CARES Act succeeded in bringing America’s poverty rate to its lowest level on record — even as the nation entered a period of pandemic-induced unemployment. Instantly improving the lives of tens of millions of working-class Americans did not come at any discernible cost to the nation’s wealthy: No spike in inflation eroded the value of their assets, no tax hikes were enacted to defray the cost of the spending. To the contrary, the giant fiscal stimulus helped to prop up consumer demand and corporate profits, making it a win-win proposition for big-dollar Democratic donors and the party’s most cash-strapped constituents. Blue America’s motley coalition of upper-middle-class professionals and the urban poor contains latent tensions. But for precisely this reason — unless or until an inflationary shock, or some other emergent event, raises the costs of loose fiscal policy — Democrats seem likely to continue in their new, defiantly anti-austerian direction.

On the other side of the aisle, the GOP’s commitment to the grotesquely unpopular policy priority of low tax rates for the superrich has long forced it to behave as though deficits don’t matter (even if they rhetorically insisted otherwise). As Republicans become more reliant on non-college-educated voters, the imperative to avoid offsetting its tax breaks to cronies with cuts to social spending will only grow more binding. What’s more, given that we’re extremely likely to see divided government at some point in the next four years, the need to reach bipartisan agreement on spending bills is also liable to pull both parties toward supporting loose fiscal policy, so long as the downsides remain low (deficit spending is the best grease for loosening legislative gridlock). And at a certain point, habitual practice will likely make lawmakers in both parties more open to economic theories that explain why they’ve been getting away with serving up so many “free lunches.”

To be sure, a lot of things could knock U.S. politics off this course. For example, there’s a significant chance that the U.S. will witness a jump in inflation in the pandemic’s immediate aftermath. Fortunate households have a lot of stored up savings and a great deal of long-delayed travel, entertainment, and dining plans. It’s possible that, right after herd immunity is achieved, demand for restaurants, hotels, concerts, etc., will far outstrip the supply, as it will take time for new firms to replace all the ones that went bankrupt over the past year. And that could lead to higher prices for many goods and services. It’s unclear whether deficit hawks will be able to use such an episode to reestablish fiscal orthodoxy.

But if U.S. politics continues to follow its current trend, then the Trump presidency will represent a pivotal era in U.S. policy-making, one that leaves both parties more interested in promoting demand and full employment than preempting inflation and policing deficits. Such a shift would not constitute quite the paradigm change that Obama described in 2008: The U.S. economy in 2020 remains more unequal and dominated by the wealthy than Ronald Reagan would have ever dared to dream.

But such a bipartisan pivot toward functional finance would make Donald Trump a more benignly transformational “policymaker” than he ever intended to be.