This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

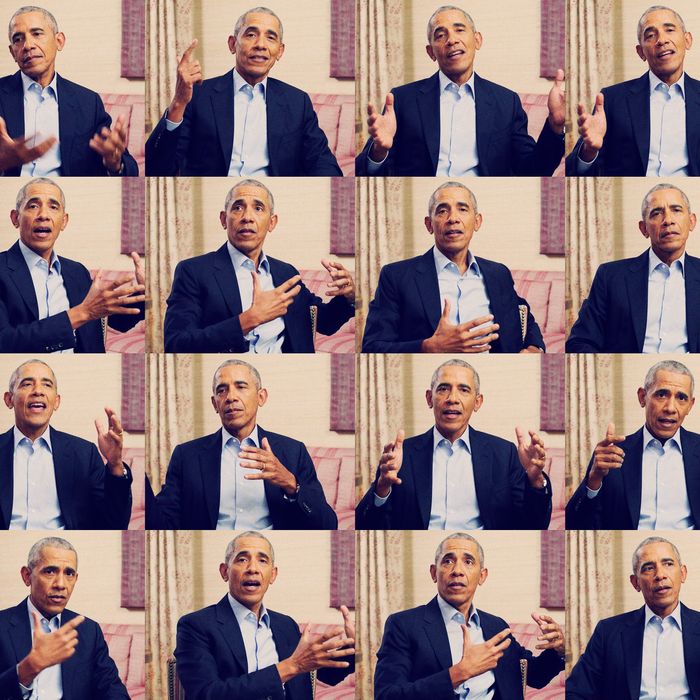

A Promised Land, the first volume of President Obama’s presidential memoirs, takes the reader through his political rise and the first two and a half years of his administration. The tension that runs through the story is between the idealism of his vision and the compromise that is required to drive change. In early December, I interviewed Obama to ask him about his legacy and political identity, how his experience may have shaped the Democratic Party that has followed him, and what sort of roadmap his presidency offers for the future of the country.

Jonathan Chait: A Promised Land addresses criticisms from both the right and the left but in different ways. When you address criticisms from the right, you’re responding to contemporaneous complaints. When you address criticisms from the left, you seem to be addressing complaints that are being made today.

Barack Obama: Yeah, that’s an interesting reading. I think the reason that I don’t address in great detail the criticism from the right is because it was so incredible. How much should I discuss the accusation that Obamacare included death panels? That’s not an interesting conversation — it was made-up stuff. I do discuss the degree to which the Republican critiques of many of our administration’s efforts were just made up out of whole cloth and the fact that they got traction not in just the conservative press but in the mainstream press. I think it is telling and important to examine, and I try to offer some clarity about the problems that still plague us and how we evaluate good policy arguments.

Whereas the criticisms from the left I do take seriously. Because some of them are at least grounded in credible concerns. I mean the fact is that we don’t have universal health care coverage. We got a starter home, as I’ve described it, that got a lot of people coverage — but there were gaps. And a public option would have helped insure that low-wage workers who made just a little too much to get the kind of subsidies they needed would have an alternative that was cheaper. And the fact that you had a bunch of states that, for purely ideological reasons or political reasons, chose not to expand Medicaid, indicates a weakness in design compared to if we had simply expanded some version of Medicare for All. So those are credible arguments, and the reason I’m interested in engaging them is because we know our job now is to consolidate the victories and gains that we made on health care — or on curbing the Wall Street excesses or on environmental protection — and building from there and being even more ambitious. And the next set of reforms and initiatives that come out of the Biden-Harris administration are going to need to take into account some of the same institutional or political constraints that I dealt with.

And so in that sense I want to take seriously the fact that, yes, we need to do more on all these fronts, and hopefully by reading the book people will say, “These constraints are real, they haven’t gone away.” And maybe people will find more imaginative ways of getting around those constraints than I was able to do. And that would be fine. But I think within the Democratic Party, and we’re seeing this even now, there is this tendency to play up this divide between the moderate center left and the Bernie-AOC wing of the party. And the truth of the matter is that aspirationally, you know, the Democratic Party is pretty unified. I don’t know of a Democrat out there who says, “Yeah, we shouldn’t have universal health-care coverage.” There are very few Democrats who would not argue that we should have significantly higher taxes, certainly on the wealthy. Or that the financial sector is bloated. Or that short-term thinking in terms of how our corporations operate because of these CEOs’ concerns about quarterly reports end up taking precedence over long-term concerns about investment and jobs and environmental sustainability. Democrats across the spectrum agree with this. And so these to me are less policy disputes than they are disputes about how you bring about change. How you work the levers of power to get stuff done.

There is a very real and legitimate debate about the idea that if we present our most preferred option and our boldest, maximalist positions, that that will inspire more voters to rally to our side; we’ll be able to break through the gridlock, win back voters who’ve become disillusioned with their lives not changing enough even when Democrats are in power, and that’s the path toward our vision. And then you’ve got folks who argue: Look, this is a big diverse country and there are actually a lot of people who are pretty conservative and don’t like higher taxes and are comfortable with their private health-insurance plan and aren’t looking for huge disruption but want sort of incremental change, and how we present our ideas and how we operate legislatively has to take them into account. And that’s really the debate, at least in my mind. And I try to have the book highlight that particular issue, because I think it really matters. I want to see a unified and effective Democratic Party advance the goals that we share.

What they say is that the Democratic Party changed its character from a New Deal party, from the Franklin Roosevelt presidency through Lyndon Johnson, and took a neoliberal turn in the ’70s, after which Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, led a neoliberal, corporate Democratic Party that doesn’t have the same fundamental aspirations of the Democratic Party of the postwar years. What do you make of that analysis?

I think there is an element of truth, but it’s not the entire or even the dominant truth. Obviously, I’m not a historian, and what I say may be a little bit overgeneralized and imprecise, but people tend to forget, for example, that FDR in 1937 went full-blown deficit hawk, right? Which is part of the reason why America lurched back into recession. And the reason he did was not necessarily because he believed that that was sound economic policy but he was trying to placate elements both within the Democratic Party and outside the Democratic Party that were bludgeoning him as somebody who was a spendthrift socialist-communist. FDR was not immune to concerns about public opinion in these issues. The New Deal itself was a hodgepodge of efforts — some of which were really significant and some of which have taken on a great symbolism in our minds but were actually pretty modest. And even the huge victories like Social Security, if you were a Black domestic worker in Birmingham, Alabama, or in Atlanta, Georgia, Social Security didn’t mean much to you. And if you had been a socialist or leftist or just somebody who wanted social justice back in the ’30s, you’d be pretty angry about Social Security because it left out huge numbers of people, deliberately, to placate racist Dixiecrats, right? Sometimes we forget that these political constraints have always operated. That’d be one thing.

What is true is that post–World War II, because of the position of the American economy, the coalition that got built based on a strong labor movement and not just laws but also customs within corporations — that say, “Let’s work with rather than against unions”; and the huge upsurge in the middle class that arises; and the relatively flat income distribution that results from the American economy being dominant when Europe is in rubble and there’s no competition coming out of Asia; you do get this golden period where workers are seeing their lives improve consistently. The market is constrained by a bunch of laws, in part because the heads of big companies, they’re feeling pretty fat and happy even with those regulations and constraints.

And it’s the combination of no-holds-barred, free-market ideology and Milton Freedman’s arguments about shareholder value, and the weakening of norms inside the corporate boardroom, combined with foreign competition that starts unraveling that social compact. What is true is that there are a bunch of Democrats who start saying, Well, yeah, maybe the free market can do it better, maybe we don’t need these regulations. And maybe unions are too stodgy and outdated and preventing increases in productivity and the key is that we have to grow the pie and not just worry about dividing the pie. And then Ronald Reagan comes in, wins over a big chunk of those same workers in a coalition despite doing everything he can to bust unions, and a bunch of Democrats think, Look, this isn’t working for us politically. And what’s a fair criticism is the fact that through Clinton and even through how I thought about these issues when I first came into office, I think there was a residual willingness to accept the political constraints that we’d inherited from the post-Reagan era —that you had to be careful about being too bold on some of these issues. And probably there was an embrace of market solutions to a whole host of problems that wasn’t entirely justified.

You also get a weakening of antitrust enforcement that in retrospect created problems long term for our economy. There was greater faith in globalization as an engine for prosperity without examining the downsides. There were decisions — for example, I write about admitting China into the global trade regime and not being as concerned about how they’re gaming the system and cheating and not anticipating that they could eat our lunch on the costs of manufacturing internally. So, I guess my point is this: I don’t think it is as clean a break between the New Deal and what you see in the ’80s and ’90s up until I become president. What I can say for certain is by the time I become president, I’m not particularly enamored with or subject to illusions about these problems.

As I write about in the book, I was pretty clear about the need to challenge China and get tougher with them on trade. I very much wanted to see stronger labor rights. I very much was interested in finding ways in which we could reduce short-term thinking and increase corporate responsibility. So the lessons that had been learned, whatever mistakes had been made from the ’80s and the ’90s on through the aughts, those were ones that I think a lot of Democrats, even on the center left, had embraced. The question remained the issue of politics and could you win back independent voters, even working-class voters, who were suspicious in some cases of the idea that if you raise taxes, somehow that’s gonna be good for me. As opposed to good for somebody else.

You detail how, in the summer of 2009, Max Baucus, the Democratic chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, held up health-care reform because he kept thinking he could get a deal with Republicans long after you told him he couldn’t. I see a parallel with President-elect Biden’s public comments, where he says he can get Republicans to make a deal with him, even though it’s not in their political interest to do that. Do you see a parallel here?

I don’t want to prejudge it, mainly because I have no regrets about at least testing the possibility that Republicans are reasonable. And that they are amenable to good arguments and are willing to cooperate to help their constituents. I think it doesn’t make sense to expect a new president to come out of the gate saying, I know those folks are going to try to obstruct, stonewall, lie, and do everything they can to defeat my proposals, and so let’s start the fight early. I think it makes perfect sense for Joe to say, Look, we just went through four years of dysfunction, and whether they want to admit it or not, Republicans in Congress know that this has been dysfunctional and maybe once Trump leaves the stage and the temperatures go down a little bit that they consider it in their interest at least early on to cooperate on some issues. And I think that what is probably a fair lesson to draw from my book and from my administration is that having extended that hand and those offers to work together, you probably just from a communications standpoint don’t want to prolong it.

It’s a legitimate criticism of my early years to say that by me leaving the door open for negotiations and communicating the desire for bipartisanship long after it became apparent that there wasn’t going to be any reciprocation on the other side, that it perpetuated certainly in the Washington press corps this idea that Well, maybe the only reason we’re not getting more legislation is because Obama’s not nice enough to Republican leaders. He’s not golfing enough with Boehner, he’s not inviting over McConnell enough for drinks. And I try to dispel that — but as you recall, that was conventional wisdom. It continues to be to some degree to this day. The notion, oh, you know, Look at Reagan and Tip O’Neill. Or alternatively, What about Lyndon Johnson grabbing people’s lapels? When we were in the White House, we just sort of used to look at that and say, “Do people know how big Lyndon Johnson’s majority was in 1964? Do they recall that when he lost that majority, all that historic legislation kind of didn’t happen?” Are they aware that for all the courtship of Reagan and Tip O’Neill, a lot of Reagan’s success, where he had it, had to do with the fact that he had gotten votes in a whole bunch of Democratic districts and so there were a whole bunch of Democrats who were scared to cross him. Because that was at a time where there was still more ticket splitting. Not to mention the fact that Reagan, for all his assertions about shrinking government, oftentimes gave Tip O’Neill exactly what he wanted. Bigger government and a bigger federal workforce and so forth.

So I think for Joe and Kamala coming in to understand that you want to make the gesture, you want that gesture to be sincere, but that there comes a point where you have to clearly communicate over and over again for the American people what the cause is for gridlock. Why something is not happening. That I think is a good lesson for them to learn.

One of the things I loved about A Promised Land is getting to view through the presidency through your eyes, seeing decisions you made as a window into your temperament and your ideology. You explain both these at almost every point where you make a big decision, but at times I wondered if there’s a distinction in your mind between your temperament and your ideology. Because they both seem so close to each other — are they the same thing in your mind?

I think they’re different things. And part of the goal of the book was to describe the distinction between what I wanted to get done in an ideal world, what I could get done given the institutional constraints of the presidency and Congress and media and other factors. My temperament probably helps determine how I approach that gap between my ideal outcome and the realities that I’m dealing with. In the book, what I try to do is describe for the reader that in fact there is a gap and leave it up to them to decide whether they would’ve made a different choice, to decide whether the decision I made undoubtedly reflects my temperament and my general assessment of what’s important. Whether that’s something they share or whether they disagree.

But I wanted them to at least understand the parameters in which I’m making those decisions. Let’s make this concrete so it’s not too abstract: I talk about something like the Recovery Act. And I think, for a long time, there’s been this notion that somehow the reason the Recovery Act package is not larger is some ideological hesitation in making it a $1 trillion instead of $800 billion. Or this was, you know, based on some concerns about deficits at a time when that should have been the last thing we were worrying about. Well, from an ideological perspective, I completely agree. I was full Keynesian at that time in terms of trying to get as much stimulus out the door as quickly as possible. And as I record in the book, I was continually pushing and prodding my team to see, “Can we get more?”

But at the end of the day I had to get Ben Nelson’s vote, I had to get Arlen Specter’s vote, and I had to get Susan Collins’s vote. Otherwise, I’m getting nothing. But in that circumstance, given a big emergency, I’m making a decision to go ahead and take three-quarters of a loaf rather than have a lengthy fight for the whole loaf that even if I win could delay things significantly and hamper our ability to right the ship. As I write in the book, there may be some who argue that it would have been worth it to take a harder ideological line to try to maximize what I would have viewed as a preferred outcome, even if it meant some short-term pain in order to restructure the U.S. economy in a way that was more fair.

And I try to be fair in the book in saying not only is that a legitimate perspective but intellectually I agree with it. But temperamentally, or from a perspective of what my job was and what my values should be as president, my belief was that the pain involved in taking a maximalist position threatened millions of ordinary folks who were losing their jobs, losing their homes. That a long, drawn-out, and potentially unsuccessful battle around those issues could have resulted in a depression. Or at least a much more prolonged and deeper recession — and that those consequences weren’t abstract. Those were the people I had met on the campaign trail, who were counting on me to make decisions that were most likely to help them as quickly as possible. So that I think is the ongoing debate even after my presidency that I’m trying to address in this book.

The same is obviously true with the Affordable Care Act. I wanted a public option. Obamacare, which was originally Romneycare, wasn’t necessarily what I would consider the ideal way to provide universal coverage to all Americans. It was based on my assessment of what we could get done during that window in which we still had a majority in the House and the Senate. And so, later, when the perception is — and I think the phrase that’s sometimes used is that a neoliberal ideology is what prevented us from getting single payer. Well, no. What prevented us from getting it was we didn’t have the votes for an approach to universal health care that scrapped the involvement of the private sector. And we tried and ultimately didn’t have the votes to get a bill through the U.S. Senate that included a public option at that time. Because I needed Joe Lieberman’s vote and I needed the vote of Ben Nelson, who is a former insurance commissioner from Nebraska.

President Trump is famous for being obsessed with your legacy and wanting to dismantle it piece by piece. Are you keeping score in your head of what you did, what he’s tried to roll back, what’s still standing?

No, it’s interesting, I don’t think about it — I don’t have a checklist in my desk where I’m like, All right, this survived, that they tried to reverse but weren’t organized enough to do. I don’t think about it in those terms. I do pay attention; I have paid attention to those areas where what the Trump administration attempted to do did some serious damage and where it’s more of a short-term setback on what is a long-term success. So although it was nip-and-tuck for a while, the Affordable Care Act remains robust. I think it’s more robust than even some really thoughtful commentators like you may have expected. Not only is it successful policy that is now actually popular, as I expected would happen, but it happened maybe four years later than I thought it would. I didn’t think it would take so long before people actually appreciated it. But it also now can be built upon, and so I feel very good about that.

When it comes to some of our climate-change regulations, there’s been some damage done. But as GM just discussed when it pulled out of the lawsuit to prevent California from maintaining the higher fuel-efficiency standards that we had set during my administration, whether it’s car companies or utilities or businesses, when they’re thinking about their energy needs, it turns out that the trajectory towards a more fuel-efficient, clean energy economy is still moving. And I think that with Joe and Kamala coming in, the ability to pick up where we left off and keep on going remains. And in some cases, there are some things that are going to be harder to undo. Even on climate change, every year you lose is a problem. So even though I don’t think it’s been reversed entirely and we can build off what we did during my administration, four years in which we made no attempt to make further progress, that’s a real loss when we’re talking about a problem as big and as urgent as climate change.

In 2009, you passed “Race to the Top,” a competitive grant that accelerated education reform across the country. Teachers unions hated it, and you stopped touting the measure publicly. Was your silence because your policy alienated a constituency whose support you needed?

I’ll distinguish between what was going on during my presidency and what’s in the book. With respect to what’s in the book, I just have a lot of stuff that I have to talk about. As it is, I think people have noted that I’ve got a 701-page book that isn’t even through my first term yet.

In volume two, I think I’ll have more time to talk about issues like education. Or immigration reform, or the work we were doing around trying to get a handle on intelligence issues and drones and so forth. So there’s a bunch of stuff that I’ll be dealing with in depth in the second volume, and education is one of those things.

During my presidency, I’m not sure it was as calculated as you just described, that this was an issue which divides my coalition. I think it has to do with the fact that our reform efforts were relatively complicated to explain to the public. It’s easy to talk about, “We’re going to put more money into buildings,” or “We’re going to talk about buying more books or science labs or you name it.” It’s harder to talk about how we’re trying to create a sense of accountability, but also one that is not loading up even more rigid standardized-testing approaches that I think a lot of teachers rightly feel are suffocating.

One of the things I try to describe in the book is: I became more modest in my confidence in explaining complicated stuff. I use the example of Dodd-Frank. Pretty successful piece of legislation, big deal, probably contributed to the fact that the financial system hasn’t buckled that much despite a historic pandemic and a huge blow to the economy this time out. And yet, after we passed it, we were trying to do a little victory lap around Dodd-Frank — nobody was really excited about how we had raised capital standards on the banks. So there’s a little bit of that going on with education. What is also true is that I was fully supportive of the idea of raising expectations, raising standards, encouraging states and local school districts not to give up on kids because it’s hard. To not assume that money is the only problem. Remember that we were also having to try to get out from under the mistakes of “No Child Left Behind,” which really did just use standardized tests as the only measure and hammered schools and punished them and was leading teachers to teach just to the test because that was the only way they were going to be evaluated.

And so how to execute that effective reform and engage teachers in a partnership in that process, that was tricky. And it’s still hard. I have a sister who was a teacher. Passionate, smart, creative. Had huge expectations for her kids and was happy to be accountable. But was also extraordinarily frustrated with the bureaucracy and testing that was coming down the pike day in and day out. I think that the best thing about “Race to the Top” was we took into account that there’s a lot of local control of education, and what we wanted to do was incentivize schools to come up with accountability measures that work. We’re not insisting that it has to be done through standardized testing. You can take master teachers and put them in the classroom. You can take into account progress rather than just flat scores. So in a school in a poor rural or inner city, a teacher may be doing a great job if students go from a second-grade reading level to a fifth-grade reading level even if it takes a year longer than it would in a suburban area — that’s okay. So we were encouraging that kind of creativity. But as I said, it’s a hard thing to explain in a national speech. And I think a lot of the unions, all they heard was accountability equals more testing. And that continues to be a challenge, I think, for nationally engineered education reform. Because, yeah, it’s true that there are times when the teachers unions just are trying to protect members who maybe aren’t doing a great job. That’s part of their job as a teachers unions. But teachers unions have also given voice to some really good teachers who rightly feel burdened by the obsession with standardized tests. So I’m more forgiving of some of the resistance than I got from them. Even though I continue to insist that that’s not an excuse to accept the status quo and more money alone is not going to solve the status quo.

It seems that the Biden administration is heading toward rolling back your education-reform legacy.

Ah, we’ll see. Here’s what I know. Joe Biden and Kamala Harris also believe that every child should get a good education and that requires changes in how we teach that go beyond just money. And I won’t prejudge both whom they’ll end up nominating as secretary of Education or the policies that they pursue until I actually see them.

Your book ends on a very poignant note, I thought, where you discuss the operation to get Osama bin Laden and wonder why domestic-policy concerns like climate change and health care can’t be carried out in the same way in the same spirit. That left me wondering, do you have any kind of long-term vision for how American politics can get there? Is that something that you think can ever happen? What’s the mechanism by which it would happen? What’s the timeframe in which that would happen? What’s your vision for getting there with it all?

There does seem to be something about human nature in which tribes, groups of people, nation-states, rally really well around fighting an enemy. And so I don’t want to pretend that we’re ever going to get the same unity around, let’s say what we just discussed, education policy, as we are about getting a terrorist who killed 3,000 Americans. But what I did want to indicate in that last chapter, because it’s something I spent time thinking about, is what would it take for us to devote the kind of resources, imagination, professionalism, creativity, expertise, when it comes to these big domestic problems as we do when it comes to getting bad guys overseas. What I try to do in the book and what I tried to do in my presidency was help us as a body politic work through the divisions that prevent us from doing that.

Race is a prominent reason why it’s hard for us to do that. Because of our legacy of race, our politics oftentimes has to deal with at least some politicians encouraging the notion that some kids aren’t worthy of our same concern because they’re not like our kids. Because they’re brown, because they’re Black, because their parents are irresponsible and so forth — so in that sense some of the awakening we saw this summer around police practices after the George Floyd murder. The larger conversation that raised, about can we have a better reckoning around the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, that’s an important piece of business. In some cases, I think that getting that unity of effort is going to require us to bridge the gap between urban and rural realities. And getting a better conversation about how rural communities depend on cities and cities depend on rural communities and how can we better integrate the economies of our country.

Here’s an example of a trend I think Democrats didn’t pick up on quick enough. Which is the incredible strength of metropolitan economies and the knowledge economy and the way in which that can hollow out rural communities that previously depended on agriculture or manufacturing, that globalization tilted further in the direction of the cities. And that created I think legitimate gripes and anger for those who were outside of it. That’s another division that I think we have to bridge. But probably, Jonathan, the biggest impediment for getting us that unity effort, and I’ve talked about this a lot both in the book and in interviews that I’ve been giving, we’ve got to solve the problem of the shattering — the splintering — of our media landscape. The fact that we just have entirely different realities depending on where we’re getting our information. And obviously we’re now seeing it in extreme form where 50, 60, 70 percent maybe of Republicans think there was a lot of fraud and cheating in this election despite the fact that there’s no evidence that there was. But as I track in the book, that started long before. And I don’t have a silver bullet for this. What I do know is that our democracy and the marketplace of ideas ultimately depends on us at least being able to share a basic set of facts and a certain agreed-upon rules of what constitutes a good argument and what constitutes proof and how do we debate issues like climate change. We can have a debate about what the proper response to climate change is. We can have a debate about how much of our response should be market based or government regulation, how much of it should be throw up our hands and say “Look, there’s not much we’re going to be able to do about this, so let’s adapt” versus “It’s not too late — let’s make some big bold changes.” We can have those debates. What we can’t have a debate about is whether the temperature is going up or not. That is the biggest thing that I’m worried about when it comes to us still being able to do big things in this country.

And it’s not going to be enough just to have a more charismatic candidate or to have a better wordsmithing of our proposals. Because one side’s not hearing the other at all. Until we can get back to the place we still were to a large degree when I ran for office in 2007, 2008, where I could go into a conservative, rural community where there weren’t a lot of Black folks and I could have a face-to-face conversation with people and they’d give me a fair hearing, and I’d listen to what they were thinking, and we could come up with some agreed-upon ideas and there was a mutual recognition that we were both hoping for the same things for our kids and for the future and what constituted fairness and how hard work could be rewarded. I could still do that in 2007, 2008, and that’s very hard to do now. And that’s the problem that I don’t yet have a solution to: the massive filter through which a big chunk of America is receiving information. More accurately, misinformation, day in and day out.

When you were president, you used to talk a lot about how the liberal racial attitudes of young people would transform the country over time. I agreed with you at the time. But seeing in the last election how Black and Latino voters moved toward Donald Trump, I wonder if it’s made you question your expectation.

No. Take a look at the voting rates of folks under 35. It’s not close. Young people overwhelmingly are supportive of a progressive agenda. Whatever their race or gender or sexual orientation. And so I remain hugely optimistic about their general perspective. You know, the fact that among Black men, Democrats, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, get 85 percent instead of 95 percent like I did, some of that is just the function of who’s the incumbent, who controls the machinery of government and messaging. Although the bully pulpit has obviously diminished, it’s still pretty powerful. You know, George Bush did a whole lot better than Donald Trump did with Hispanic voters. And so I would say that these blips, all they indicate is the fact that progressives shouldn’t take anything for granted. I’ve never been somebody that subscribes to “demographics are destiny” in politics — you gotta earn votes. The Hispanic community is actually many communities, and you gotta win votes. I actually did really well with young Cuban voters. That’s why I won Florida twice. But that’s not a given. (In some ways, the surprise was that I did win young Cuban votes given the historic connection between the Cuban American community and Republicans.) So campaigning matters, showing up matters, reaching out matters, and that’s true in every demographic. And that won’t change any time soon. But what we consistently see evidence of is that when it comes to racial attitudes, when it comes to an insistence that our economy should be fairer and more just and should result in less inequality, when it comes to how we preserve this planet, young folks got it all over on us. And part of what I’ve been trying to consistently encourage is: How can we get more and more of those young people into leadership positions? And how can we make sure that their voices are heard?

One of the things that we saw during Black Lives Matter protests, or in debates around economics, is that young people are going to want to reach for what’s best and are less likely to want to compromise or shade how they present things. They’re going to be more disdainful of pragmatism and half-a-loaf. And that’s how it should be. That’s how America changes. And so when I said earlier I worry about this obsession with the center left versus the hard-core left or picking up on every possible disagreement between AOC and Nancy Pelosi, or this debate about how much of the results of the congressional elections were because they were playing up Black Lives Matter protests — my general attitude is that I want the next generation to push harder. There’s a different role for activists as opposed to people once they’re actually elected in Congress trying to get a bill passed. And there are going to be times when young people are impatient or consider themselves obligated to speak truth to power even if it might offend some swing voters somewhere. That kind of messiness is okay. Because what they’re doing is stretching the boundaries over time of what’s possible. And I use an example in the book where I got beat up by some activists because it took us a good solid year and a half, two years to get “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” repealed. It didn’t feel good when I was getting heckled. But I didn’t begrudge folks demanding that that get done, because it was the right thing to do. On the other hand, my obligation was to see if I can get this to stick — which meant that I had to coax the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Bob Gates, my Defense secretary, to ultimately be supportive of that, because I knew that was the only way I could get it through Congress. That sort of both-and strategy for progressives is important. We need each other. It goes back to the New Deal: A. Philip Randolph and FDR meeting and A. Philip Randolph is demanding FDR take bold action on civil rights and FDR turns to A. Philip Randolph and says, “I completely agree with you. Make me.” It’s somewhat apocryphal, but it’s been repeated a lot, because that actually is both sides of the coin of an effective political party. You’ve got the push for the promised land out there, and you’ve got the professionals saying, “Yeah, I want to get there too, but we got a cliff here and a chasm there and a river there and we’re going to have to map this out.” Both are necessary to ultimately arrive.