The vaccines are finally here, but how quickly will a country reeling from COVID-19 really feel their effects? I spoke with deputy editor David Wallace-Wells about America’s coming inoculation.

Ben: The race for the vaccines has been one huge bright spot amid the depressing overall response in America. Pfizer began rolling out its shots to high-risk Americans this week, and videos of people getting them have served as the encouraging side of our pandemic split screen — the other side being record cases, hospitalizations, and deaths (more than 3,400 on Wednesday). Moderna, whose extraordinarily quick development of its vaccine you wrote about, is expected to get emergency authorization from the FDA on Friday, so by next week we’ll likely have two candidates in use. Based on what you’ve seen, are you optimistic right now that the general rollout will go smoothly?

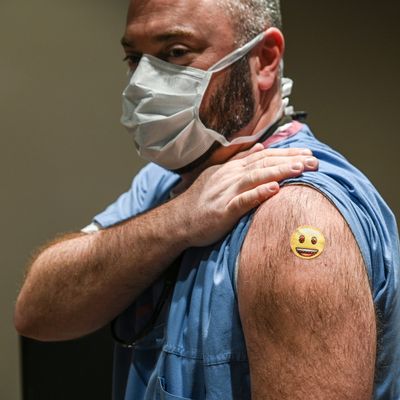

David: Depends what counts as smoothly! There was a lot of anxiety this year about public suspicion of the vaccines — not just anti-vaxx energy but a broader skepticism about what risks there were with such a new, largely untested injection (or injections). As far as I can tell, the polling on that is somewhat all over the map: I’ve seen some polls showing only a quarter of Americans are eager to get the vaccine, and polls showing that more than three-quarters are. Some of the polling outfits that have been tracking willingness over time have seen the numbers rise somewhat dramatically with the early efficacy results, so that’s good. And on that point, the design of the rollout is helpful — most of the first wave of recipients will be health-care workers, who are as a group very likely to want the vaccine and can sort of “demonstrate” further safety to the broader public by the time the second wave begins. What worries me more is the practical side of it. I don’t think most Americans yet really understand where they are supposed to go to get the shots, which is not a surprise, given what a messy, kludge-d together health-care system we have. It’s one of many reasons this pandemic has made me long for a much more centralized medical system.

We’ve already had a couple of instances of adverse reactions — someone who had a severe allergic response that required medical attention. It’s not clear how many of those we’ll get, but surely this one won’t be the last. I don’t think that will have a significant effect on public willingness, but it remains to be seen.

Ben: Undoubtedly some holdouts will remain, but in terms of reaching herd immunity, would a relatively small number who refuse to get the shot be a big problem?

David: At the moment, we’ve got many fewer doses than people willing to take them, so some limited amount of opting-out isn’t a very big deal. If there’s a massive anti-vaccination movement through the spring, that begins to get more problematic. On the other hand, personally, it’s hard for me to see such a movement growing large enough to really impact the prospects for herd immunity, assuming the vaccines continue to be as effective as they appear to be a few months into trials. Fifty percent of the country gets the flu vaccine every year, for instance, and, as we all know, COVID-19 is much scarier than the flu. Unless there are some really scary outcomes in the early rollout. I think you have to assume well more than 50 percent of the country will take the vaccine.

We don’t know exactly where the threshold of herd immunity is — the rough, back-of-the-envelope calculation has been 60–80 percent of the population, and some earlier calculations suggesting lower thresholds seem to have been disproven. But 20 percent of the country, roughly, has already had the disease, and of course, community protection isn’t a binary thing, with the disease spreading uncontrolled when 59 percent of the community has had it and then disappearing entirely when you hit 60 percent. The more people have immunity, the slower the spread.

Ben: I’ve seen some people, including coronavirus prophet Zeynep Tufekci, express some alarm about the U.S.’s vaccine prioritizations. The shots are going first to health-care workers and people at long-term care facilities. It’s kind of a muddle as to who gets it next, with workers in various high-risk fields on the shortlist. But her point is that this virus kills people over, say, 65, and especially over 80, at vastly disproportionate rates to everyone else. Does it make sense to simply vaccinate every older person possible first, and worry about everyone else later?

David: In theory, it could be. But older people are also at much higher risk of adverse reaction (and much more vulnerable to even “mild” reactions), and there hasn’t been much testing in the trials of older people (especially not-optimally-healthy older people). In fact, the one person on the FDA advisory panel with eldercare experience voted against prioritizing the elderly for this reason, though my own reading is that this is excessively cautious.

Big-picture, though, I think this does remind us all that in fact the disease is much, much, much more dangerous for older people — especially very old people. I think people understand that, in principle, but don’t appreciate, at all, the skew — where a 90-year-old is 100,000 times more at risk than a 10-year-old, for instance, and many thousands of times more at risk than even a 50-year-old.

Public-health messaging has really emphasized the universal risk, I think as a way of incentivizing public investment in containment measures like social-distancing and mask-wearing. But the risk is skewed very, very dramatically.

Ben: We’re seeing just devastating numbers of deaths, hospitalizations, and cases every day, and have been for weeks on end. Some terribly hit Midwest states are seeing declines, but that’s being made up for in places like California, where things just keep on spiking. What is the consensus on when the vaccines hit enough people that they might, on their own, make a difference in some of these statistics?

David: In general, every person vaccinated makes a difference, just a very small difference. In the big picture, I don’t think there is such a consensus, but honestly, I think it will take a while for a dramatic turn. I don’t think the first-wave rollout will make much difference — not to engage in stereotyping or paint anybody with too broad a brush, but I’m guessing that while there is some transmission among health-care workers today, they are as a group behaving in very careful ways such that the spread we are seeing is coming from other communities. I think, for the time being, the effect of those vaccinations will be trivial compared to other spread dynamics throughout the country — and it may even be the case that the news of imminent vaccines has given some feeling of license to the population at large to loosen up a bit, driving numbers up further. But … as with everything else, we’ll see.