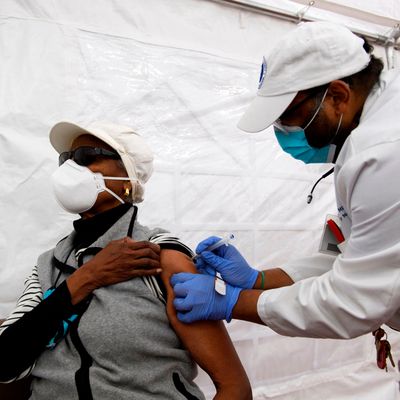

Throughout the United States, Black, Latino, and Native Americans have faced more difficulties accessing pandemic care, as well as higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalization and death than whites. The trend — a result of decades of health-care inequity in the United States — has continued as states race to vaccinate residents before coronavirus variants potentially push caseloads back up in the early spring.

Earlier this week, an analysis from the Kaiser Family Foundation determined that the 17 states reporting vaccination data by race and ethnicity are failing to vaccinate Black and Latino residents at the same rate as whites. In Mississippi, 15 percent of vaccine doses have been administered to Black people, though they make up 38 percent of the state’s coronavirus cases and 42 percent of deaths. Hispanic residents in Texas also make up 15 percent of total vaccinations, though they account for close to 40 percent of the population.

An analysis from the Associated Press published on Saturday expanded on the trend. In Maryland, although Black residents make up 30 percent of the total population and 40 percent of health-care industry workers, only 16 percent of those vaccinated so far are Black. In Chicago, Black residents make up 30 percent of the population but only 15 percent of those vaccinated. And in Philadelphia — where the city recently entrusted a college student to administer thousands of doses rather than have an Ivy League medical school do it — Black residents have received just 14 percent of vaccines, though they represent 40 percent of the population. Latino residents have a similar disparity, representing 15 percent of Philadelphia’s population but just 4 percent of those vaccinated.

Partial vaccination data provided by New York City is also showing an alarming racial gap in the nation’s former COVID epicenter. Of the almost 300,000 residents who have received their first dose, 15 percent were Latino and 11 percent were Black — despite the city being 29 percent Latino and 24 percent Black. This gap was even more severe among the most vulnerable New Yorkers: Only 9 percent of those over 65 who have gotten their first shot are Black. In a joint press conference on Sunday, public advocate Jumaane Williams and comptroller Scott Stringer described the disparity and other rollout failures as “almost criminal” and a “national embarrassment.”

As the Associated Press notes, factors expanding the gap include a “deep distrust of the medical establishment among Black Americans because of a history of discriminatory treatment; inadequate access to the vaccine in Black neighborhoods; and a digital divide that can make it difficult to get crucial information.” To help bridge the divide, the Biden administration has encouraged states to use CDC data to place more vaccination resources in vulnerable neighborhoods. However, building out vaccination centers in areas in which residents are underrepresented in the effort hasn’t been a perfect solution in New York. According to the City, local Spanish speakers who attempted to get a dose at the Fort Washington Armory in Washington Heights were unable to do so without the aid of translators. But the vaccination site — in a neighborhood in which 69 percent of residents are Hispanic — did see patients traveling in from New Jersey and Westchester to get doses.

“Good news: I volunteered as an [appointment verifier] at the Armory,” Dr. Susana Bejar tweeted on January 24, noting that around 2,400 people were vaccinated. “Bad news: the majority of ppl being vaccinated were not from the low-income predominately Latino neighborhood of Washington Heights.”

The situation at the Fort Washington Armory was resolved: As of late last week, only New York City residents currently eligible for the vaccine could sign up to be vaccinated there, and 60 percent of appointments have been reserved for those living in the neighborhood. But the phenomenon of state residents traveling into the city to get shots is occurring throughout the boroughs. The partial data provided by the city states that about 94,000 of those who have received the vaccine in New York City do not live within its boundaries.

In an interview with the New York Times, City Council health-committee chair Mark Levine proposed several measures to end the “vaccine equity gap,” which include giving scheduling priority to communities of color and to streamline the online process to sign up. “We need to take action now to fix yet another egregious case of inequity in this pandemic,” Levine said. Mayor Bill de Blasio, meanwhile, anticipates that expanded vaccine access will help correct inequities: “I honestly believe that’s the single best cure to this problem.”