In recent days, Mitch McConnell has publicly argued that Donald Trump provoked the January 6 Capitol Hill riot — and Trump has privately suggested that he may form his own political party.

The former president (God, that feels good to type) is almost certainly bluffing. Building out the infrastructure of a pro-Trump “Patriot Party” — and then getting it onto the ballot in all 50 states — would require a lot of work, which has never been Trump’s strong suit. And it would also be irrational: Trump remains the GOP base’s top choice for the 2024 nomination.

But this does not mean that his reported discussions of the proposition are insignificant.

One of the biggest questions hanging over American politics right now is how Trump will choose to deploy the peculiar form of power he has amassed. The billionaire is one of the most widely reviled public figures in the country. Yet he is also the most influential man in Red America. And more than any other ex-president in modern American history, Trump is indifferent to the fate of his party (in which he was always an interloper) or its ideological project (much of which he adopted for self-promotional use only). Which puts the Republican Party in a novel and hazardous position.

There is a reason why virtually the entire Republican firmament — from Fox News to Ted Cruz to Lindsey Graham — decried Trump as a con man during the 2016 primary: They had no basis for trusting this former Hillary Clinton donor’s fealty to the conservative movement. At that point, Trump did not owe the GOP’s donor class, or aligned institutions, anything in particular. Once Trump secured the nomination, and apprehended the scale of the resources that a general-election campaign would require, he cut deals with the party’s major interest groups. From that point until November 3, 2020, Trump’s interests and the Republican Party’s remained in rough alignment: He needed the GOP to safeguard his corruption and aid his reelection, and the GOP needed him to keep the Democrats out of power and liberal judges out of the judiciary. After November’s election, a more tenuous alliance remained in place through January 5, as Trump leveraged the GOP’s need for his base-mobilization services in Georgia’s Senate runoffs to secure the party’s complicity in his attacks on the legitimacy of the 2020 results. Once David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler were defeated, however, McConnell ceased to have any use for Trump, who was once again a mere rival for intraparty power. The Senate majority leader proceeded to denounce Trump’s quest to overturn the election from the Senate floor — and Trump proceeded to incite an insurrection that sent McConnell into hiding.

Since then, McConnell and other members of the Republican old guard have grown more unabashed in their efforts to reclaim the party from Trump. McConnell has even expressed openness to voting for Trump’s conviction in his forthcoming Senate impeachment trial. Among long-tenured GOP officeholders, there is a powerful desire to pocket the spoils of its Faustian bargain (hundreds of billions of dollars in tax savings for the party’s largest shareholders, a 6-3 Supreme Court majority for its Evangelical foot soldiers) while consigning Trump himself to the dustbin of history.

But this objective may prove as quixotic as the mogul’s Mexican-financed border wall.

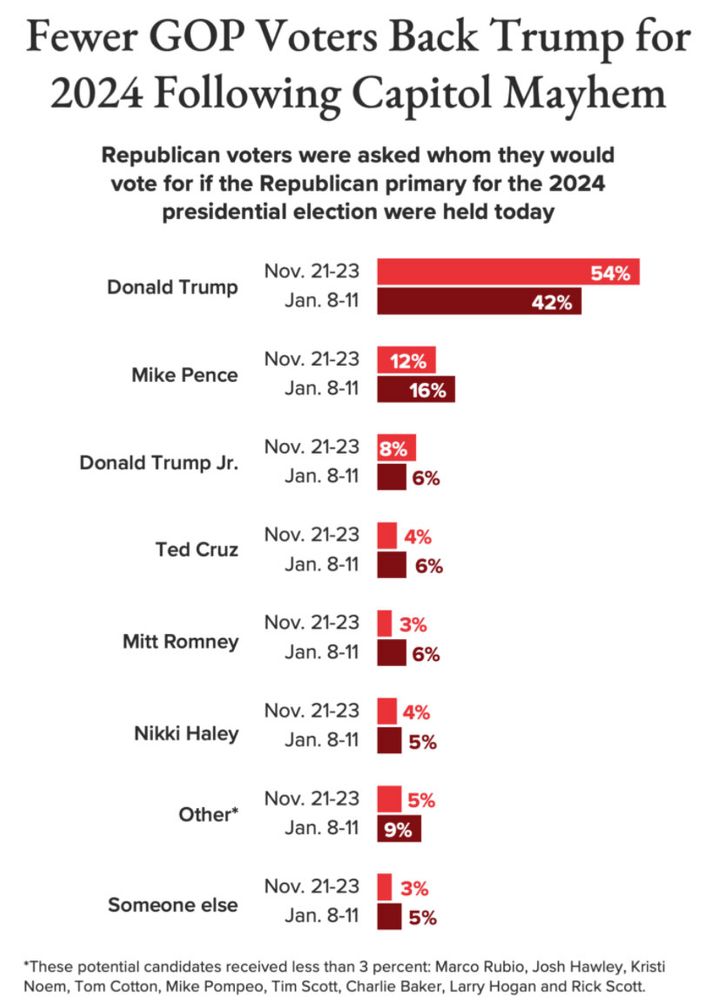

In its latest tracking poll, Morning Consult finds that 81 percent of GOP voters approve of Trump — while just 32 percent say the same about McConnell. Meanwhile, as already indicated, in post–Capitol Hill riot polling, Trump has retained a (diminished yet nonetheless) massive lead over other hypothetical 2024 GOP primary candidates.

And among Republican voters, his incitement of the insurrection effectively enjoys more esteem than McConnell’s criticism of it.

Put simply, if conventional Republicans were capable of dictating ideological terms to their base, Trump never would have been president. The mogul earned the affection of the Republican rank and file through his unequivocal opposition to immigration, willingness to affirm their most conspiratorial suspicions about Barack Obama, and, above all, his status as a fellow conservative-media super-consumer. The durability of that affection is reflected not only in Trump’s poll numbers but also in the posture of the House GOP. In the Senate, Republicans are relatively insulated from their primary voters by six-year terms and, in many cases, a level of name recognition and in-state clout that they’ve built up over decades. But every Republican in the House had to face their base in 2020 and will again in 2022. This divergence is almost certainly a major reason why a majority of House Republicans objected to the certification of the 2020 results, even as only eight of their Senate colleagues — all of whom were either first- or second-termers — did the same.

All of this puts the GOP in a difficult bind. On the one hand, there is a high risk that failing to distance the party from both Donald Trump and his most crackbrained supporters will prevent the party from regaining purchase with Romney-Clinton voting suburbanites — whose votes it may need in order to compensate for a drop in turnout among less reliable white rural voters mobilized by Trump’s celebrity. On the other hand, the party now lives at Trump’s mercy. The mogul almost certainly isn’t willing to put in the effort that establishing a new party would require. But he could devastate the party of his betrayers without breaking a sweat: If Trump told his voters to sit out the 2024 election to punish Republicans for treating him unfairly, all available evidence suggests he could demobilize enough of the GOP base to render victory impossible. And Trump has often displayed greater wrath toward his turncoats than he has toward his known enemies.

All of which is to say: Unless 2024 finds Trump in prison or the grave, the Republican Party will need to find a way to keep itself in his good graces.