This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Alex Johnson was a senior at the University of Texas at Austin, pursuing a career in politics, when he first heard from John Weaver, the legendary Republican operative living nearby. It started with a direct message on Twitter. “I just didn’t really think anything of it at first,” Johnson told Intelligencer. “But then, you know, his intentions became clear.”

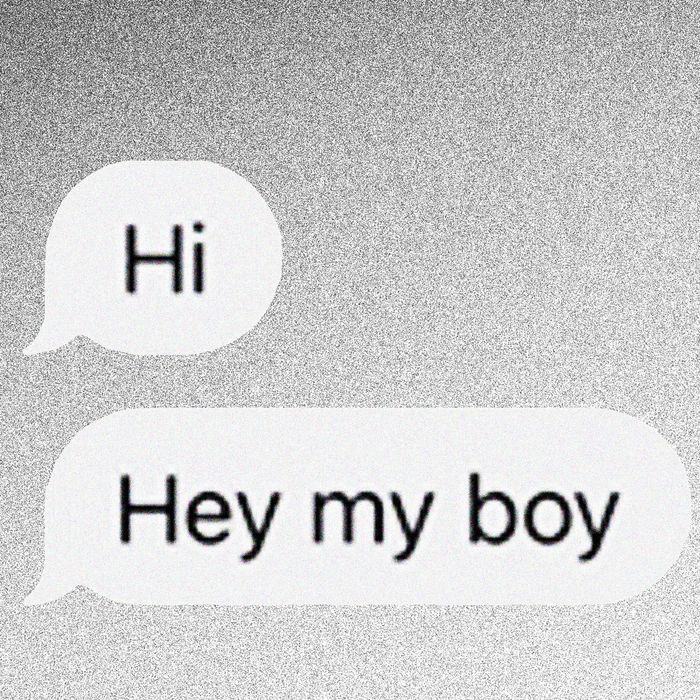

Weaver, who worked on both of Senator John McCain’s presidential campaigns, started by discussing politics or college football before asking Johnson about his dating life and sexual interests. “You interested in getting together? working together? etc?…,” Weaver wrote in December 2018, according to a message Johnson shared with Intelligencer. “I want to see you,” Weaver wrote four days later.

The pattern continued into 2020, when Weaver reached out to Johnson about working for a new political-action committee he had co-founded: the Lincoln Project.

Weaver started the group with some of the biggest names in Republican politics to defeat Donald Trump. Joining him was Steve Schmidt, a Karl Rove protégé during George W. Bush’s reelection campaign, known for his no-holds-barred style of attack, who later worked on McCain’s 2008 campaign. Joining them was another McCain veteran, Reed Galen, and the Republican strategist Rick Wilson. Other co-founders included the Republican super-lawyer George Conway, husband of Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway, as well as veteran Republican political operatives Mike Madrid, Ron Steslow, and Jennifer Horn.

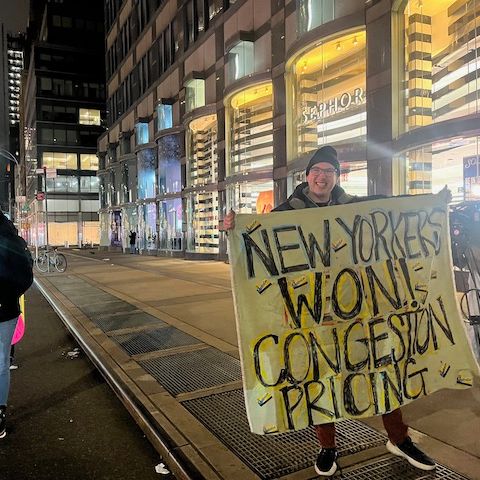

It didn’t take long for the Lincoln Project to become a haven for “Never Trump” Republicans and capture the political world’s attention with its brutal television ads against the president. The buzz led to big business for the super-PAC, which raised more than $87 million in the 2020 election cycle, according to Federal Election Commission records. Much of the money was paid to firms run by the Lincoln Project’s co-founders, including nearly $25 million to Summit Strategic Communications, a firm run by Galen. More than $20 million was paid to TUSK Digital, run by Steslow, which employed people who worked as contractors at the Lincoln Project.

“Would like to put you in touch with some of our folks,” Weaver wrote to Johnson on April 23, suggesting he come be an intern. Fifteen minutes later, he added: “On [your] walk, think about worshipping a big cock and having yours worshipped and you rimmed till you beg!”

Weaver also made phone calls to Johnson. Once, he said, Weaver called to ask him his thoughts on the Lincoln Project and its ads — then quickly segued into what felt like an attempt at phone sex. “We were talking about the Lincoln Project, and maybe getting me involved, and of course I think that’s awesome. I’m like, ‘Oh, yeah, that would be great!’” Johnson said. “Then he asked me: ‘When’s the last time you jacked off?’”

Johnson said he rarely answered Weaver’s calls after that, but despite his discomfort with the Lincoln Project’s co-founder, he took the internship there and started in July 2020, working remotely from his home in Texas. “This was a big opportunity in my view to make a difference in the political world,” Johnson said. “And so I was pretty quick to say ‘yes.’”

Weaver continued harassing Johnson at the Lincoln Project: “Are you top, bottom, versa?” he wrote in one message shortly after Johnson started.

“His messages never stopped,” Johnson said. “And I would play along, just to be nice. Because I knew, I mean, he’s important. Like he has the strings. And we operate in the same kind of political culture of being ‘Never Trumpers.’”

Johnson said he didn’t tell Lincoln Project management about Weaver, fearing retribution if he accused one of the company’s co-founders of harassment. “I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, if I say something wrong, they’re gonna let me go or get rid of me,’” Johnson said.

While Johnson didn’t know it then, the Lincoln Project had already been told Weaver was preying on young men in and outside the company.

On June 17, a person working at the Lincoln Project sent an email to co-founder Steslow that reported ten allegations of Weaver’s harassing men, including at least one employee at the Lincoln Project; three people independently described the contents of the email to Intelligencer and said it warned Weaver could be using his position at the company to make promises of career advancement to prey on young men. The complaint called Weaver’s predatory behavior an immediate threat to the company that, if it became public, could render a death blow to the Lincoln Project’s reputation. As the complaint noted, the Lincoln Project itself was attacking Trump as a sexual predator. Steslow raised the email with his fellow co-founder Galen and corporate counsel Matthew Sanderson, the AP reported. Yet Weaver’s harassment continued. (Weaver did not respond to requests for comment.)

Schmidt told Intelligencer: “There is no human being, no person involved with the Lincoln Project who made any type of allegation of any type of inappropriate communication that would have triggered an HR investigation or the hiring of an outside counsel to conduct such an investigation,” he said. “There were zero allegations, complaints, media interrogatories directed to the Lincoln Project with any specificity, at any time about, any misconduct, towards any person.”

Schmidt said that all the Lincoln Project had heard was “chatter” in early July that Weaver, who is married to a woman, was gay. Around this time, sources say, reporters were asking Lincoln Project members about Weaver. Schmidt noted the rumor dates back to at least 1988, when Weaver’s nemesis in Texas, Karl Rove, reportedly spread a rumor that Weaver took a pass at a male campaign staffer. He said the Lincoln Project called Weaver to warn him of what Schmidt labeled “the rumors” and asked Weaver if he needed to tell them anything else.

“I said, ‘You need to know that this is out there. Is there anything that we need to know?’” Schmidt said of their phone conversation. “He said, ‘No, it’s bullshit. It’s not true.’”

The company’s leaders told the New York Times in January they had not been aware of such allegations until they publicly surfaced that month, contrary to the complaint received and circulated by Steslow. The Times reported Weaver had sent messages that ranged from provocative to sexually explicit to 21 men going back years, including to one recipient who was 14 years old, though none worked at the Lincoln Project.

Four former members of the Lincoln Project called on the company to free them to speak about Weaver. “Lincoln Project contractors and employees are calling on the organization to release anyone with knowledge of harassment or who has been harassed by John Weaver from their nondisclosure agreements so that they can speak freely about what happened to them, or what they know about what happened to others,” they said in a statement to Intelligencer.

“I really wanted to believe everyone that they didn’t know the extent of it,” Johnson told Intelligencer of the Lincoln Project’s claims they were unaware of complaints against Weaver until this year. “They made it seem like this was out of the blue and there wasn’t even a baseline knowledge at all. This just seems like they were lying; it seems like they were not being truthful to me.”

Johnson said that Schmidt had called him following the Times story in January to apologize for what Weaver had done and offered to pay for his therapy.

Johnson was not alone among interns who say they were harassed by Weaver before starting at the Lincoln Project: One of them was Charlie Stephens, who was a 19-year-old rising sophomore at Louisiana State University when he was contacted by Weaver this past June. Weaver asked him if he or any of his “peers” might be interested in an internship “to help kick the shit out of Trump and against Senate Republican incumbents,” according to Twitter direct messages Stephens shared. Stephens said he was interested, and Weaver responded that he’d be “perfect.” A week later, Stephens told Weaver he formally applied to the role. “You are a fucking stud!” Weaver said. When Stephens demurred, saying that was “quite the compliment,” Weaver responded, “Take it! Hell, you may very well be ;).”

Stephens was hired in July on Weaver’s recommendation and placed at Steslow’s firm — after Steslow was warned Weaver might be offering jobs to victims. (Steslow did not respond to requests for comment.)

Stephens said that how the situation has played out now makes him question why he was hired and his worth while working at the company. “Looking back on it all, I kind of wish we would have realized this entire makeup of this is odd,” said Stephens of Weaver and the company. “I was like, “Damn, is that really why I got this internship?’”

Former employees faulted the Lincoln Project for continuing to hire the interns recommended by Weaver after receiving a warning he would dangle job opportunities to potential victims. “It’s just enraging to know that they were enabling and they perpetuated this kind of behavior. And didn’t take action until it just came out,” said one former employee. “There was knowledge of Weaver and his history, and yet there were people directly brought on who were recommended by him, so I still don’t know what to say why that was the case.”

In August 2020, Weaver took a medical leave of absence from the Lincoln Project owing to what Schmidt and Wilson called a cardiac problem. Weaver practically disappeared from company business around the time, former employees said, leading them to believe the company had sidelined him over the allegations.

Beginning in September, much of the Lincoln Project’s staff convened in Park City, Utah, where they hunkered down in a COVID-safe pod until Election Day. By this time, the allegations against Weaver were an open secret in the company, according to former employees. One former employee said that’s when his boss warned him to avoid Weaver. “When I was told, it was almost in passing that I did not want to be involved with Weaver specifically because I am a young man,” the former employee said. One night over drinks with much of the staff, four employees recall, Weaver’s behavior came up repeatedly as a topic of discussion. One person remembers Schmidt and co-founder Rick Wilson telling people Weaver was “depraved” and “twisted” and that they wouldn’t want to know the truth about him. “The Weaver stuff is being taken care of,” Schmidt said, according to another. Wilson told Intelligencer this account was “untrue,” and when asked, Schmidt said it was “not true.”

In the fall, Weaver reemerged. The Lincoln Project said Weaver “proposed a large scale operation” that it rejected, which former employees said was a plan to flip Texas for Joe Biden. The former employees said they were surprised to hear from Weaver again in conference calls and group emails. The Lincoln Project said it “declined” to reengage with Weaver but did not elaborate. Weaver did appear on an October 11 episode of 60 Minutes about the Lincoln Project, which interviewed the co-founders.

“I was under the impression that it was being handled,” said one former employee who learned of the Weaver allegations in Utah. “I was in a position where I trusted that it was being handled, given that we were working on this cause that was rooted in morality, was rooted in truth and rooted in doing the right thing.”

In mid-October, Weaver also started communicating with Johnson again, asking about him and “Aggie boy,” the term he used to reference Johnson’s boyfriend. “You in town this week?”

After Trump was defeated the following month, the Lincoln Project’s future looked bright with plans to become a media business. But the company soon began to shrink. Many of the interns left after the election. In December, co-founders Steslow and Mike Madrid left the company. Then the allegations against Weaver moved into public view: first on Twitter, then at The American Conservative, and finally the Times.

“To the men I made uncomfortable through my messages that I viewed as consensual mutual conversations at the time: I am truly sorry,” Weaver said in a statement to Axios last month, in his only public comments about his conduct. “They were inappropriate and it was because of my failings that this discomfort was brought on you.” Weaver stood by the Lincoln Project, saying its “defense of the Republic and democracy is vital.”

Schmidt told Intelligencer that as soon as the Times story published, he sent an email to Weaver that read: “Fuck you, John. 14-year-old boy. Fuck you. You are a liar and a predator. You have no honor. Thank God McCain is gone. Fuck you.”

The Lincoln Project also condemned its co-founder as “a predator, a liar, and an abuser” in a statement around the same time, and said the company was shocked by the allegations. “The totality of his deceptions are beyond anything any of us could have imagined and we are absolutely shocked and sickened by it. Like so many, we have been betrayed and deceived by John Weaver. We are grateful beyond words that at no time was John Weaver in the physical presence of any member of The Lincoln Project.” Co-founder Jennifer Horn resigned days later, citing the scandal.

Weaver, in his statement, said he is not finished with his life’s work: “I hope that by telling this truth at long last my family and I can move forward. I plan to continue the fight for liberty, justice and human rights that has been my life’s work.”

Johnson is not as certain he wants to continue in politics, saying he worries Weaver’s behavior wasn’t the exception in the industry but the rule: “I’m afraid this stuff goes on more than anyone knows.”