At the end of last month, Jeffrey Riley, the Massachusetts commissioner of education, announced that his goal was “to bring all elementary-school students back to in-person learning five days a week this April.” The state would achieve this, he noted, by allowing children to be three feet apart. It was a stark rejection to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which conspicuously maintained its recommendation of six feet of distancing in its revised school guidelines released in February.

For most schools, the difference between three feet and six feet determines whether children can attend school full time or not. Requiring six feet between each student and staff member means classes must operate at reduced capacity, leading to so-called hybrid schedules where kids are only in the building part time.

The Massachusetts edict didn’t stop with just ignoring the CDC’s distancing guidelines. Riley also said schools should reopen fully in person or in a robust hybrid model “regardless of community prevalence.” The CDC’s school guidance, by contrast, hinges on varying levels of community prevalence as benchmarks for whether and how schools can open.

It’s not just Massachusetts. Colorado allows for three feet in schools. As does Ohio, where a number of its schools have been running full time in person the entire school year. West Virginia’s Board of Education announced that by March 3, pre-K through eighth grade must offer five full days per week of in-person instruction, regardless of community rates. In Miami, the nation’s fourth-largest school district, schools have been open full time since the fall, in part because the Florida Department of Education allows students to be closer than six feet.

This snubbing of the CDC on schools guidance cannot be chalked up to mere partisan politics. Colorado is led by a Democratic governor. Massachusetts, despite having a Republican governor, is as deep blue as any state in the country.

Numerous epidemiologists and infectious-disease doctors have noted that the CDC’s six-foot guidance and tethering school openings to community transmission does not reflect the science. A study published by the CDC itself at the end of January showed minimal in-school spread with students generally not maintaining six feet of distance. Further, the study found that even with community rates topping 40 percent, in-school transmission remained low. Tracy Hoeg, one of the authors of the study, when asked, noted that she didn’t know how the CDC even came up with its community thresholds for how and whether schools can open.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, experts have argued that adhering to six feet of distancing in schools is not only based on questionable science but is especially damaging because it prevents nearly all schools from operating at full capacity. With this in mind, the World Health Organization marks one meter (approximately three feet) for distancing in its school guidance. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health cites three feet of distancing as acceptable if everyone is masked. The American Academy of Pediatrics wrote in its guidance at the beginning of the school year, and in its updated guidance in 2021, that while six feet of distancing is ideal, three feet is sufficient, and cautioned against strict adherence to six feet if that forced students into remote learning. This summer, a professor at Harvard Medical School and the chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital told the mayor of her town that in schools “if people are masked it is quite safe and much more practical to be at three feet.” That professor is Rochelle Walensky, the new director of the CDC.

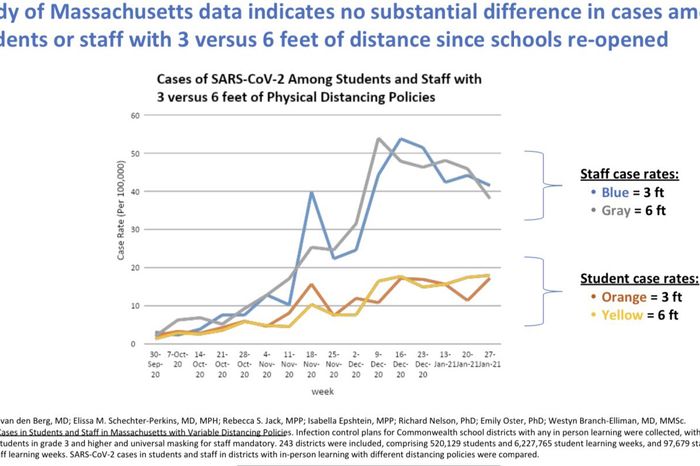

For some time, the recommendation, and resulting dispute, on distancing in schools has been based on conjecture from indirect evidence from past studies. Last week, however, a study on this exact point was presented by Commissioner Riley in Massachusetts. They study was based on direct data from September through January, comprising more than 520,000 students and nearly 100,000 staff in 243 school districts across the state. The conclusion: There is no substantial difference in cases among students or staff with three feet versus six feet of distance.

If that isn’t convincing enough, a report by the ABC Science Collaborative, a working group of scientists and educators, run by the Duke School of Medicine, basically did a point-by-point takedown of the CDC guidance. Among a number of issues addressed, the report said three feet is sufficient; regarding the CDC’s chart of community rates, it stated: “Community transmission has extremely limited scientific merit and no school-based, individual-risk data to support it.”

With all this in mind, the average parent could be forgiven for lacking confidence in the CDC’s conclusions on sensible school guidelines, and for feeling frustrated that the agency’s dubious recommendations are hampering schools from opening.

Exacerbating the problem is that the CDC’s guidance is both overly specific, citing a variety of metrics like six feet and community rate benchmarks rigidly pegged to color-coded danger levels, and also unnecessarily complex; the latest school guidance clocks in at around 15,000 words of dense text. The language has enough hedges and qualifiers that any side can choose which passages they want to highlight. To take just one line from the guidance: “Physical distancing (at least six feet) should be maximized to the greatest extent possible.” Those advocating for schools to open to as many children as possible highlight “to the greatest extent possible.” Those who are more hesitant, such as many teachers unions, highlight “at least six feet.” Requiring non-specialists to apply scrupulous attention to guidelines to make sense of them is not a good recipe for public health messaging.

Moreover, when parents of kids functionally under house arrest in a remote learning district see children in a neighboring state or even neighboring town attending school full time, and with no apparent difference in community infection rates or infection rates in the schools themselves, they will naturally expect explanations. Yet there is a lack of a clear justification from the CDC on why it is sticking to a six-foot standard even as other authorities and health agencies are recommending a more flexible one; nor is there a satisfying explanation for its seemingly arbitrary community rate thresholds. Both of these guidelines lead to reduced attendance or fully remote learning, and delay getting kids back to school full time.

Science is messy, and it’s a good thing when there is dispute and discussion. But when that’s the case, it behooves the CDC to go out of its way to articulate clearly and succinctly why its guidance is correct. The agency should explain to Americans why kids in Europe, across a wide range of countries, cities, and school facilities, not to mention kids in states within our own country, are operating under different metrics than what it’s recommending, and, by and large, are no worse off for it. Perhaps there’s a persuasive reason. But we have yet to hear it.