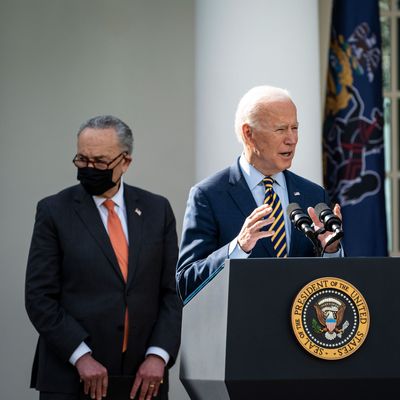

Securing congressional approval of most elements of Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan was not only a great start for the Democratic trifecta that controls both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. It was also a fine example of legislative craftsmanship and leadership needed to enact such a large and complicated bill with virtually no Democratic defections (including none at all in the Senate).

What comes next will be harder.

The contents of that first big bill were known well before Biden took office, the timing was dictated by its packaging as a COVID-19 emergency relief and stimulus package, and the legislative strategy for enacting it became clear the moment Senate Republicans made a puny opening compromise offer. Democrats had the luxury of being allowed two uses this calendar year of the budget reconciliation process that bypasses the Senate filibuster; under the Congressional Budget Act one per fiscal year is allowed, and none were enacted last year. So technically the COVID-19 bill was the budget reconciliation bill for Fiscal Year 2021 (which began last October), and Congress can now enact another one for Fiscal Year 2022.

Assuming Senate Democrats cannot muster unanimous support for abolishing or restricting the filibuster, passage of any significant legislation will have to go through one of two avenues: reconciliation or a bipartisan deal with at least 10 Republicans. The latter approach is inherently problematic, for all the reasons associated with partisan polarization. And even if Republicans become interested in a specific Biden proposal— an infrastructure package, for example — they will likely object to any effort to pay for new spending with tax increases rather than the domestic spending cuts most Democrats are certain to oppose.

According to the New York Times’ Jim Tankersly, the White House is indeed planning to propose a big infrastructure plan offset by tax increases:

The first legislative piece under discussion, which some Biden officials consider more appealing to Republicans, business leaders and many moderate Senate Democrats, would combine investments in manufacturing and advanced industries with what would be the most aggressive spending yet by the United States to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change.

It would spend heavily on infrastructure improvements, clean energy deployment and the development of other “high-growth industries of the future” like 5G telecommunications. It includes money for rural broadband, advanced training for millions of workers and 1 million affordable and energy-efficient housing units. Documents suggest it will include nearly $1 trillion in spending alone on the construction of roads, bridges, rail lines, ports, electric vehicle charging stations and improvements to the electric grid and other parts of the power sector.

That’s the dessert. Here’s the broccoli:

Officials have discussed offsetting some or all of the infrastructure spending by raising taxes on corporations, including increasing the corporate income tax rate above the current 21 percent rate and a variety of measures to force multinational corporations to pay more tax in the United States on income they earn abroad. That strategy is unlikely to garner Republican votes.

Barring some unexpected breakthrough, then, the infrastructure package will have to either languish or go into a second reconciliation bill. But then there will be other Biden agenda items (like the infrastructure plan, they are associated with his campaign’s “Build Back Better” talking points) that will probably need to proceed via reconciliation as well:

The second plan under discussion is focused on what many progressives call the nation’s human infrastructure — students, workers and people left on the sidelines of the job market — according to documents and people familiar with the discussions. It would spend heavily on education and on programs meant to increase the participation of women in the labor force, by helping them balance work and caregiving. It includes free community college, universal pre-K education, a national paid leave program and efforts to reduce child care costs. That plan would also extend or make permanent two temporary provisions of Mr. Biden’s recent relief bill: expanded subsidies for low- and middle-income Americans to buy health insurance and tax credits aimed at cutting poverty, particularly for children.

This “plan” would apparently cost up to $2 trillion, and would also require the kind of revenue offsets that will make significant Republican support as unlikely as Mitch McConnell coming out for abolition of the filibuster.

But even if all of the above represents the outer boundaries of Team Biden’s legislative ambitions for 2021, congressional Democrats could have other ideas, as Politico suggests:

Influential factions within the Democratic caucus are also making the case to include more provisions using the budget process. The Congressional Hispanic Caucus wants to include the White House’s immigration bill, which would offer a path to citizenship for 11 million people who have been living in the U.S.

Like the $15 minimum wage that was originally part of the American Rescue Plan, immigration provisions would be vulnerable to a Senate parliamentarian’s exclusion based on the arcane Byrd Rule limiting reconciliation bills to budget-germane provisions that don’t produce net costs after a decade. They could still be included in a House version of a reconciliation bill, but that would be politically risky since it would increase pressure on the White House and Senate Democrats to overrule the parliamentarian, which Biden clearly does not want to do (and which centrist Senate Democrats might oppose as well).

So figuring out what’s in the second reconciliation bill this year is a complicated, politically fraught, and highly consequential decision that requires careful coordination between the White House and Democrats in both congressional chambers (with careful attention to both progressive and centrist sentiments).

Some key pieces of legislation (particularly those that are unlikely to affect economic indicators) can, of course, simply be postponed until next year, when a new, Fiscal Year 2023 reconciliation bill will become available. But there is a reason for the ancient maxim in Washington that controversial legislation is rarely enacted in an election year. And the more sobering reality for Democrats is that if important items on the party wish-list aren’t accomplished this year or next, they may recede into the far distance, given the historical likelihood of Republican gains in the 2022 midterms.

There is a lot riding, then, on the strategic decisions Democrats make in the next few weeks. If they “go big” on a reconciliation bill, Republicans can be expected to go very loud in attacking them. And at every step in the road ahead, the risks incurred by miscalculation grow larger and more expensive.