Last November, a plurality of Georgia voters supported a Democrat for president. The leader of the Republican Party responded by declaring the results fraudulent and himself the election’s true winner. These claims were baseless and Georgia’s Republican secretary of State refused to say otherwise. As a result, Brad Raffensperger went from being a rising star in the Peach State GOP to one of its pariahs. Both Republican candidates in Georgia’s Senate runoffs called for the secretary’s resignation. Subsequent reporting confirmed the mendacity of the president’s fraud allegations — and revealed that Trump had told Raffensperger, “I just want to find 11,780 votes” (to cover the margin of defeat by Biden). Nevertheless, after word of the president’s illicit demands were made public — and after his lies had inspired an insurrection that put all of Congress in physical danger — a majority of the Republican Party’s House members voted to nullify the 2020 election results.

Less than six decades ago, Georgia was an authoritarian white ethno-state. At that time — and for the bulk of the state’s post-emancipation history — the preferred political party of white Georgians subordinated democracy to racial hierarchy by enacting facially neutral voting laws that disenfranchised virtually all of the state’s African Americans.

This is the context for Georgia’s newly passed election law. And it is indispensable for understanding the character of that legislation.

In recent days, conservatives have derided Democratic complaints about the measure as “crazy” and “alarmist” and based on “myths.” They have noted that — while the law places new restrictions on mail-in voting — it also expands opportunities for early in-person voting and keeps Georgia’s overall election regime more accessible than those of many blue states. As Ilya Shapiro argues in National Review, New York, Delaware, and Connecticut all have more restrictive early-voting laws than Georgia does — and yet progressives aren’t calling for boycotts of those states, even as they’ve coerced Major League Baseball into moving its All-Star Game out of Atlanta.

But when you account for context — and acknowledge the bill’s most nefarious provisions — the left’s purported “double standard” disappears. The leading lights of Georgia’s Republican Party spent the past five months validating baseless allegations of a stolen election and demonizing their own secretary of State for refusing to do the same. The GOP’s 2020 standard-bearer is still decrying the treachery of Republican election officials who failed to abuse their powers at his behest. The party’s leader in the Senate contends that “voting is a privilege.” And all across the country, Republican lawmakers openly argue that Americans who live in cities are less deserving of political representation than those in (predominately white) rural areas. There is no equivalent to any of these behaviors on the other side of the aisle.

Thus, what happened late last month in Georgia can be summarized as follows: A political party that is openly hostile to neutral election administration, the political equality of urban America, and the ideal of popular self-government imposed new restrictions on ballot access — and greatly increased its own power to disqualify voters and decertify election results — in a state that was still governed by Jim Crow rule when Joe Biden went to college.

More concretely, Georgia’s election law gives the GOP’s gerrymandered state legislative majority control of the state elections board and empowers that body to overrule county-level elections boards on matters of vote counting and voter eligibility. Before the law’s enactment, Raffensperger chaired the state elections board; now, the secretary of state is no longer one of the board’s voting members. This is disturbing in two respects: The political impetus for stripping this power from the secretary of State was (1) red America’s desire to punish Raffensperger for failing to “find” the votes that Trump requested, and (2) shifting power from the secretary of State to the legislative majority means shifting authority from an official who was elected by statewide popular vote to a caucus that is almost exclusively accountable to white rural areas.

All of which is to say, Democrats are not hysterical or delusional for viewing recent events in Georgia as an extraordinary assault on democratic principles.

And yet, it is also true that the law’s restrictions on no-excuse mail-in voting are not extraordinary relative to those of other states, and that it will be easier to vote in Georgia in 2022 than it was to do so in New York as recently as 2018.

Progressives are understandably exasperated to see the media treating “Is it bad for an openly anti-democratic political party to consolidate its power over election administration?” as an issue with two equally legitimate sides. But we should not allow such exasperation to blind us to the fact that in Georgia — and across the U.S. — restrictive voting rules are not actually the primary driver of either racialized political inequality or right-wing minority rule.

Voting restrictions (still, for now) ain’t what they used to be.

Over the weekend, Nate Cohn made a version of this point in a widely derided analysis of the Georgia law’s likely effects on voter turnout. The scathing response to Cohn’s article wasn’t entirely unwarranted. The piece’s framing, which foregrounds a lament about the bipartisan tendency toward “exaggeration” in politics, and downplays the context of Jim Crow or January 6, enabled conservatives to declare, “See, even the liberal New York Times says the Dems are being hysterical.” But Cohn’s primary argument — that there is little basis for assuming that Georgia’s new voting rules will significantly impact voter turnout — is sound.

One can quibble with his parsing of discrete pieces of data or research papers. For example, he notes that in 2020 “turnout increased just as much in the states that didn’t have no-excuse absentee voting as it did in the states that added it for the first time.” Yet it is possible that, in the absence of Democratic investment in voter education and mobilization in states with more restrictive mail-in voting laws, a turnout discrepancy would have surfaced. Nevertheless, Cohn’s basic point remains: The kinds of voting restrictions that Georgia just enacted have not proven to be reliable tools for suppressing voter turnout. Notably, many Republican consultants agree with this analysis. As one Georgia GOP operative anonymously told the Washington Post in February, “There’s still an appetite from a lot of Republicans to do stuff like this, but it’s not bright. It just gives Democrats a baseball bat with which to beat us.” The concern expressed here — that restricting mail-in voting will do more to mobilize African Americans and alienate suburban moderates than disenfranchise Democrats — has an empirical basis.

In the eyes of America’s small-d democrats, restrictive voting laws shine with a special menace, as these were the primary impediment to free and fair elections for much of our nation’s history. But they are not the chief obstacle today. And it’s important for Democratic lawmakers and activists to appreciate this fact, because if they don’t, there’s a chance that they will fail to uproot the true foundations of right-wing minority rule in the contemporary U.S.

H.R. 1, congressional Democrats’ democracy-reform bill, does a great deal to make voting more convenient. And such provisions are worthwhile both normatively and strategically. Although there is limited evidence that you can significantly increase turnout by making voting easier for Americans who are already registered, automatically registering voters (as the Democratic proposal would) has proven effective at increasing democratic participation. And the bill also redresses the most odious and effective form of voter suppression in the U.S.: the disenfranchisement of former felons.

But H.R. 1 does little to preempt partisan interference in election administration, which is the most dangerous aspect of the Georgia law, and the bill doesn’t do nearly enough to address the systematic underrepresentation of Democratic voters at all levels of government — which is the primary source of race-based political inequality in the contemporary U.S.

Voter-ID laws are among the more onerous and racially discriminatory voting restrictions that Republicans have been enacting in recent years. Most research on their impact nevertheless finds that they have only a small to negligible effect on voter turnout; at the high end, some papers suggest such laws reduce overall turnout by 3 percent. That’s theoretically enough to flip an exceptionally close election (although, given the GOP’s newfound reliance on non-college-educated supporters, it’s far from clear that the subset of Americans whose ballots would be suppressed by voter-ID laws are overwhelmingly Democratic). Gerrymandering and Senate malapportionment, however, disempower Black voters in a manner that is exponentially more profound and unambiguous.

Unequal representation is disenfranchisement by other means.

For the entirety of this millennium, the median U.S. House district has been at least 2 points more Republican than the nation as whole; for most of the past decade, the House map has had a pro-GOP bias of more than 4 percent. Which means that he preferred political political party of white America doesn’t need to win a majority of House votes nationwide in order to control Congress’s lower chamber, while the preferred party of Black America needs to win it by a hefty margin. This is a direct consequence of the hyperconcentration of Black voters in select urban districts, which is itself a legacy of de jure segregation.

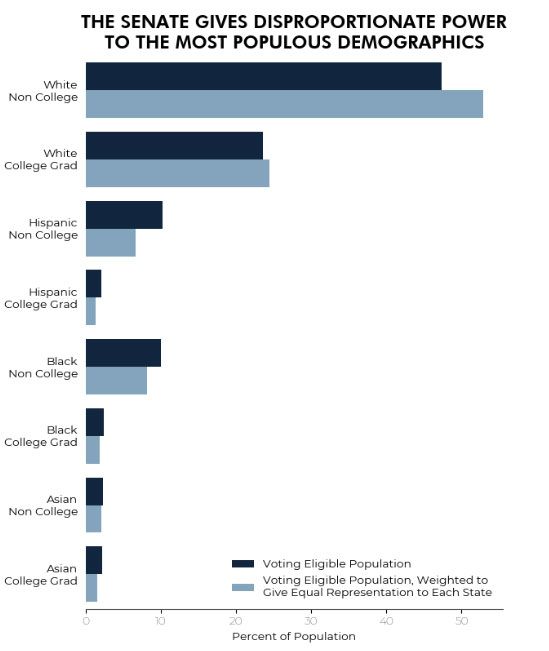

The Senate’s bias is even more severe. Thanks to 19th-century efforts to gerrymander the upper chamber, the middle of our country is chock-full of heavily white, low-population, rural states. In our present age of urban-rural polarization, this has rendered the median U.S. state nearly 7 points more Republican than the nation as a whole. It has also left African American voters wildly underrepresented in the Senate.

Since 2000, the GOP’s Senate caucus has never represented more voters than their Democratic colleagues. Yet the preferred party of white Americans has controlled the upper chamber for more than half of the past two decades.

The systematic underrepresentation of Black voters in Congress is every bit as grave an affront to equal citizenship as voting restrictions are. The pro-Republican biases of America’s House, Senate, Electoral College, and state legislatures have poisoned American political life, and done profound harm to Black communities. Were the U.S. president elected by popular vote, and Congress governed by proportional representation, the GOP would never have held unified federal power this century, and a liberal majority would reign over the Supreme Court. In such a world, the Voting Rights Act would still be intact, and funding for social welfare and urban communities would almost certainly have been higher over the past 20 years. Put differently: Under a more democratic system of representation — in which every American’s partisan preference counted equally, irrespective of where he or she lived — the GOP would have either been locked out of power for the past three decades, or else forced to make greater concessions to the interests of nonwhite voting blocs.

Thus, the difference between voter-ID laws and partisan gerrymandering is not that the former is a direct attack on racial equality, while the latter is merely grubby politics. Rather, the difference is that voter-ID laws could hypothetically deny African American voters their rightful share of political power — if the few studies showing large turnout effects are correct, and a given House or Senate race happens to be historically close in a particular election year — while partisan gerrymandering automatically denies African American voters their rightful share of political power every single election year, in many states and districts across the country.

What’s more, absent congressional action, partisan gerrymandering is about to become even more severe. Thanks in part to the biases of state legislative maps, the GOP controls far more state governments than the Democratic Party does, and are poised to dominate the post-Census redistricting process.

Given these realities, anyone concerned with promoting democratic equality in the United States should consider forbidding partisan gerrymandering a top objective, and combating voting restrictions like those in Georgia, a worthwhile but far less pressing endeavor. Unfortunately, congressional Democrats seem to be operating on different priorities.

Who’s afraid of proportional representation?

H.R. 1 does mandate nonpartisan districting, but its provisions on that subject are weaker than they could be. At present, the bill bars redistricting plans that are “likely to result in partisan bias” on the basis of “quantitative measures of partisan fairness,” and then lists several different potential metrics, which are liable to produce contradictory verdicts over whether a given map is acceptable. In other words, there is no single binding criterion. And the absence of such a clear requirement will make it easier for our Republican-dominated judiciary to block challenges to partisan maps.

Writing the legislation this way is a choice. It is entirely within Congress’s constitutional powers to mandate something akin to proportional representation in the House. For example, Congress could order states to make the percentage of Democratic-leaning House districts in their maps match the state’s partisan lean in the previous presidential election. Which is to say, if your state voted 51 percent for Joe Biden and 49 percent for Donald Trump, then about half of your House districts should be more Democratic than the country as whole, and half more Republican. This would dramatically advance political equality. Right now, 61 percent of North Carolina’s House districts are more Republican than America (and all of those seats are occupied by GOP lawmakers). Under the proportional representation rule, the state would need to redraw its maps such that roughly 50 percent of its districts leaned right.

Yet even as they decry Georgia’s limitations on mail-in voting as the new Jim Crow, House Democrats are declining to mandate equitable representation. As Vox’s Andrew Prokop reports:

[S]ome reform supporters have advocated for using proportionality as the standard for a legal map — clearly setting the standard for a fair map so that if, say, a party’s House candidates get 60 percent of the votes in a state, they should get about 60 percent of the seats.

But Democratic House aides emphasized that a broad change to this part of the bill is extremely unlikely — because the politics of redistricting reform have been tricky enough for House Democrats to grapple with already. That’s both because reforms could end up redistricting some House members out of their jobs, and because the party’s slim majority means almost every Democrat’s vote is necessary. (For instance, in Massachusetts, all nine members of Congress are Democrats, even though about one-third of the state voted for Trump in 2020. A proportional standard would put some of their seats at risk.)

The bill’s drafters have also had to grapple with reluctance from some in the Congressional Black Caucus, some of whose members fear the drive for partisan balance will result in the dilution of the safe majority-minority districts they currently represent. Rep. Bennie Thompson of Mississippi was the sole Democrat to vote against HR 1 and cited the redistricting provision as one reason why.

Thompson’s avowed concern here is baseless. Decades ago, when white southern Democrats still existed in large numbers, there may have been a genuine conflict between spacing Democrats evenly across districts and guaranteeing that many members of the House would be accountable to majority Black constituencies. But today, if you dramatically expand the number of Democratic-leaning House districts, you are also going to increase the number of blue districts with majority-minority Democratic primary electorates. For this reason, Democratic data scientist David Shor estimates that a stringent proportional-representation standard would likely increase the number of nonwhite representatives in the House by 16, with Black legislators in the South accounting for the vast majority of those legislators. Thompson’s position is therefore not a defense of African American political power, but merely of his own.

Meanwhile, the concerns of the Massachusetts delegation could be mitigated by increasing the size of the House, thereby allowing the Bay State to retain nine Democratic representatives while also adding some Republican ones to achieve proportionality. Granted, for incumbent Democrats who feel safe in their present seats, any change to congressional maps can look like a threat to their job security, if not in a general election, then in a primary. But some things should take precedence over maximizing one’s odds of reelection. When Georgia Republicans facilitate the underrepresentation of Black voters for the sake of strengthening their grip on power, congressional Democrats decry it as a betrayal of the Republic. They should hold themselves to at least as high a standard.

To be sure, the imperfections in H.R.1’s language aren’t the primary obstacle to countering partisan gerrymandering. The filibuster and Joe Manchin are. The House has at least passed a democracy-reform bill that formally prohibits partisan redistricting. The main problem right now is that this legislation is bottled up in the Senate.

But this is another reason why it is vital for progressives to be clear-eyed about where the gravest threats to U.S. democracy are coming from. If H.R. 1 makes it through the upper chamber, it is going to do so in altered form. The 800-page bill contains a dizzying array of provisions with disparate sources of opposition. To the extent that a clean, anti-gerrymandering and D.C. statehood bill would be easier to pass in isolation, small-d democrats should be clamoring for such a proposal. For now, Manchin’s list of the H.R. 1 provisions that he is prepared to support includes mandatory early voting but not redistricting reform.

The problem with exaggerating the extremity or likely impact of Georgia’s restrictions to mail-in voting is not that doing so is unfair to Republicans; it’s that such exaggerations can distract media and congressional attention away from more potent and unambiguous threats to political equality in the U.S. If progressives allow sentiment and symbolism to preempt unblinkered analysis, they will leave themselves vulnerable to misleadership. It is in the interest of craven Democratic incumbents for voter-ID laws to loom larger than Senate malapportionment or gerrymandering in the democracy-reform debate, since combating the former does not threaten their power, while combating the latter just might.

It is in the interest of democracy, however, for proportional representation to become so salient to blue America, Democratic incumbents feel that they can’t preserve their own power without giving their coalition its fair share.