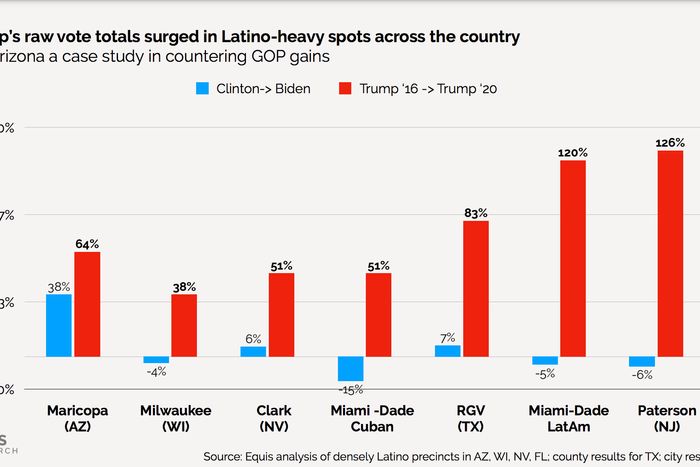

On November 3 of last year, Miami-Dade County gave the Democratic Party a panic attack. Florida was the first major swing state to report its ballots in the 2020 election, and returns from overwhelmingly Hispanic — and, heretofore, overwhelmingly Democratic — precincts showed the incumbent president making massive gains with a demographic he’d spent five years disparaging. If the trend among Hispanic voters was remotely representative of the broader electorate’s mood, Donald Trump was about to win reelection in an Electoral College landslide.

Of course, that did not happen. Ultimately, the Democrats’ gains with college-educated white voters more than offset their losses with Hispanic ones. But those early returns from Miami-Dade still boast a prominent place in Democratic consultants’ nightmares.

And for good reason. Florida’s vote wasn’t a preview of the country’s. But the rightward shift of Hispanic voters in Florida was indicative of that identity group’s voting behavior nationwide. Despite the rich diversity among this catchall demographic category, all across the country, areas with large Hispanic populations moved sharply right in 2020, even as the broader electorate moved left.

For Democrats, the Hispanic shift doesn’t just represent a brush with electoral annihilation narrowly averted. Rather, the development raises doubts about the durability of the party’s majority coalition: Were Hispanic Americans to follow the same political trajectory as the “white ethnics” of yore, then it would become even harder for Democrats to overcome the geographic concentration of their core constituencies, and thus, remain competitive in the Senate and Electoral College.

For this reason, progressive number crunchers have spent much of the past few months trying to discern the cause of Trump’s gains with the demographic. In an interview with Intelligencer last month, Democratic data scientist David Shor outlined one account of the 2020 results. His story goes like this: Democrats have long relied on the backing of Hispanic voters who self-identify as “conservative.” Such conservatives often have left-of-center views on economic policy, but lean right on issues of crime and policing. In 2020, Hispanic conservatives began voting more like white ones, and this was especially true of those who espoused the most right-wing views on “law and order” in policy polls. Therefore, Shor surmises that the heightened salience of policing issues following the George Floyd protests — and the Democratic Party’s association with “defund the police” in some media coverage of those protests — played a major role in driving Hispanic defections.

This narrative has been contested for a while now. For example, Tom Bonier, CEO of the political-data firm TargetSmart, has noted that Biden was already underperforming among Hispanic voters in public polls before the George Floyd protests, and that the Democrat did not suffer any obvious decline in support during the furor over “defund.” Nevertheless, detailed, public analyses of the demographic’s rightward shift in 2020 have been hard to come by — until last Friday, anyway.

Equis Research, a progressive data firm dedicated to analyzing Hispanic voters, released an in-depth report late last week that does not contradict Shor’s analysis, but does complicate it. Drawing on 41,000 total interviews with Hispanic voters in battleground states, voter file data, precinct returns, and focus groups, Equis offers the following insights into the largest demographic shift in American politics last year:

1) There’s a blurry line between “persuasion” and “turnout.”

Among highly engaged Democrats, any discussion of disappointing election results has a high chance of turning into an ideologically fraught debate over whether low turnout or inadequate persuasion was responsible for the party’s woes. Historically, progressives have tended to favor “low turnout” as a diagnosis and more organizing of the disenfranchised — and sharper distinctions with the GOP — as prescriptions. Moderates, meanwhile, have tended to insist on the primacy of inadequate persuasion and counseled triangulation as its antidote.

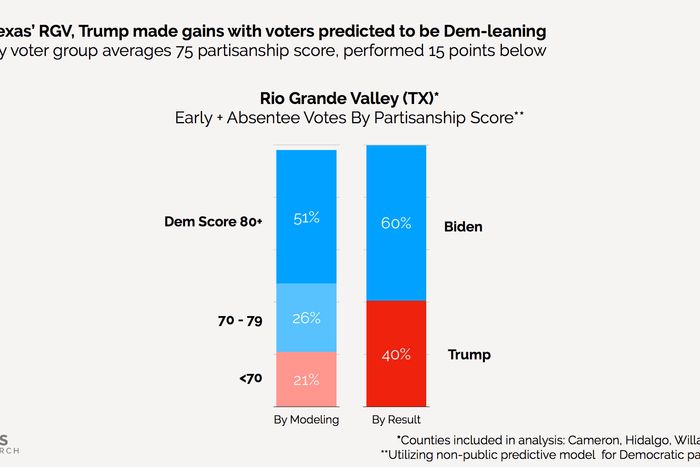

But Equis’s report suggests that “persuasion or turnout” is a false binary. Its data indicates that Trump made significant gains with Hispanic Americans who were both previously left-leaning and unlikely to vote. In other words, Trump persuaded these Americans and mobilized them.

In an analysis of ballots cast early in the Rio Grande Valley, Equis used a proprietary model to estimate the likely partisanship of voters (presumably based on the historic voting pattern among Americans with their fine-grained set of demographic characteristics). Twenty-one percent of early voters fit the profile of likely Republicans; Trump won nearly double that.

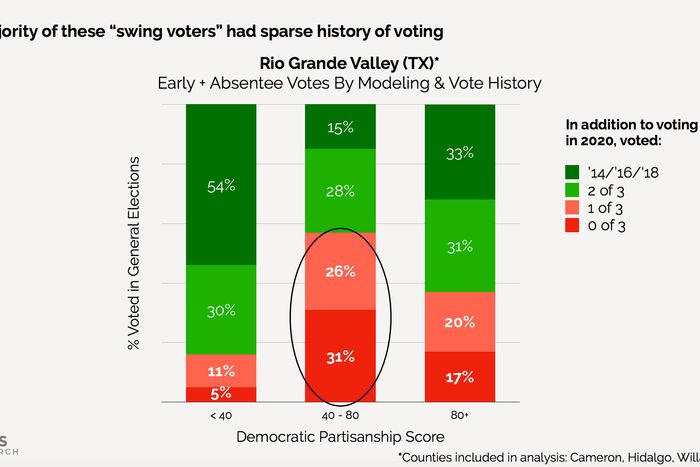

Some 57 percent of those early voters had participated in no more than one of the previous three federal elections.

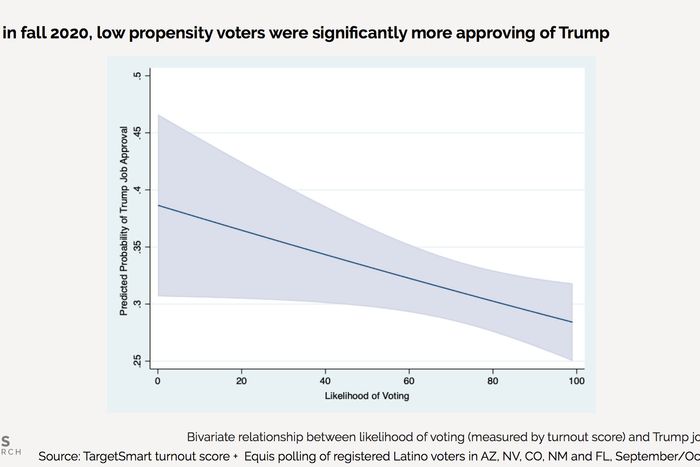

All of which suggests that Trump won over a significant number of previously nonvoting, non-Republican Hispanics. And this interpretation is supported by another finding from Equis’s polling: In 2019, low-propensity Hispanic voters approved of Trump at about the same rate as high-propensity ones. But by fall 2020, low-propensity Hispanic voters had become markedly more likely to approve of Trump.

This defies conventional wisdom, which has held that low-propensity Hispanic voters are at least as Democratic as high-propensity ones (after all, more reliable Hispanic voters tend to be more affluent and native-born). Again, this suggests a significant number of Hispanic Americans went from being left-leaning election abstainers to Trump voters in 2020.

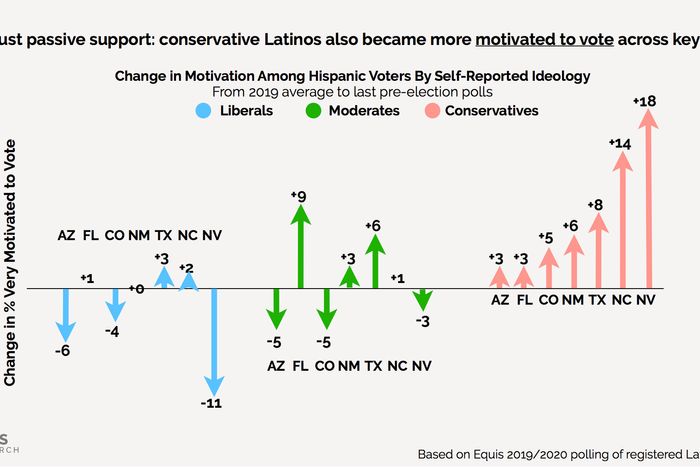

All of this said, Trump’s success in mobilizing conservative Hispanics is certainly part of the story.

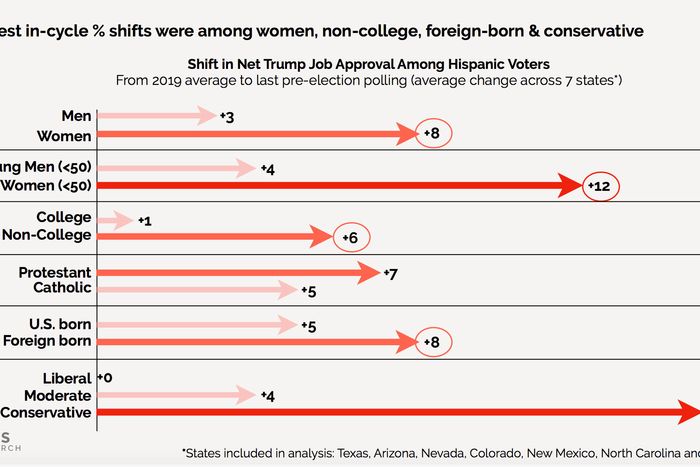

2) Despite speculation about his “macho” appeal, Trump made his biggest gains with Latinas.

Trump’s gains with Hispanic voters were apparent in preelection polling (even if the magnitude of those gains was not). In October, the New York Times entertained the theory that Hispanic men were driving this trend, as Trump appealed to their “machismo culture.” And on one level, the election results are consistent with that hypothesis: In absolute terms, Trump performed better with Latinos than Latinas.

But Equis’s polling suggests that between 2016 and 2020, Trump gained far more ground with Hispanic women:

David Shor told me that he has observed the same trend in his own data. And he argues that the concentration of Trump’s gains among Latinas is consistent with his hypothesis that “defund the police” influenced Hispanic voting behavior since, in his polling, women rank crime as a more important issue than men do. A connection this tenuous seems unlikely to persuade the unconverted. For its part, Equis offers no firm theory on why Latinas in particular shifted right. Its report also neither affirms nor rebuts the notion that the heightened salience of policing played a role in the broader shift among Hispanic voters.

3) Many Clinton-Trump voters appear to have been motivated by economic anxiety.

Equis evinces more confidence in its account of which voters moved toward Trump than in its explanations of why they did; the latter is explicitly framed as a work-in-progress.

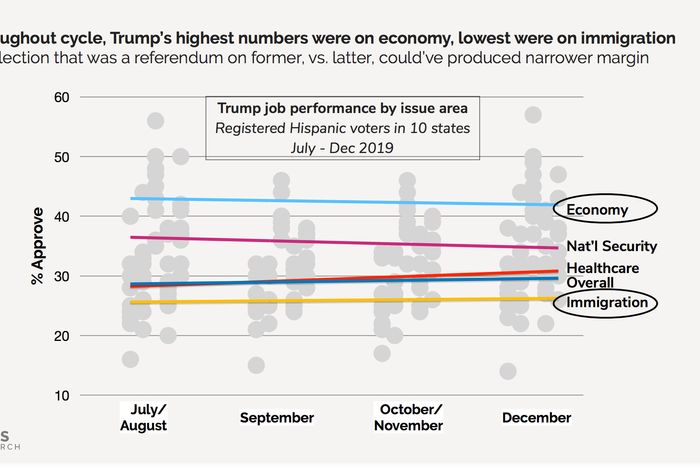

But the firm does put forward a compelling hypothesis: The GOP’s hard-line posture on immigration had previously kept a segment of self-described conservative Hispanics aligned with the Democratic Party. But the pandemic reduced the salience of immigration to these voters, while increasing that of the economy. And the COVID crisis had a similar effect on less ideologically inclined, low-propensity (and/or low-information) Hispanic voters, who had made economic gains during Trump’s first three years in office, but suffered economic losses during the pandemic and feared that Biden would be a worse economic manager than a famous businessman (and/or that the Democrat would subject the country to a prolonged lockdown).

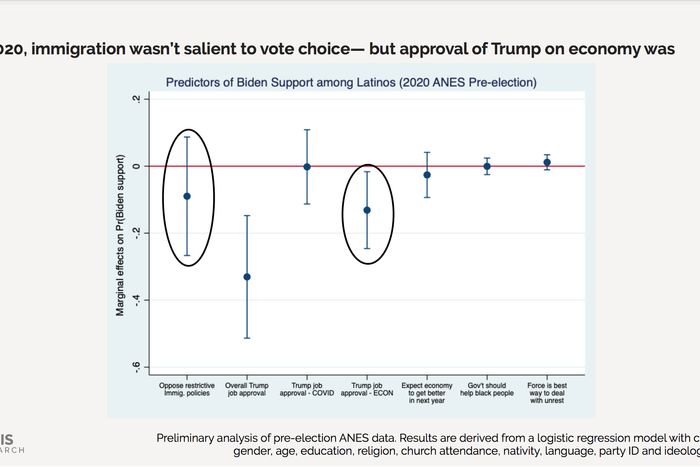

The most direct evidence for this account comes from (generally, unreliable) focus-group responses. But the narrative is supported by more statistically robust findings. Equis shows that in 2016, whether a Hispanic voter opposed restrictionist immigration policies strongly predicted their partisan preference; in 2020, however, this variable was far less relevant than a voter’s position on Trump’s economic management.

Further, Hispanic voters consistently gave Trump far higher marks on the economy than they did on immigration.

Equis’s framing of this point implies a prescription: If Democrats wish to keep conservative Hispanic voters in their camp, they’d do well to heighten the salience of immigration, both by calling attention to Republican xenophobia and enacting comprehensive immigration reform.

And that’s where the firm’s analysis is most in tension with David Shor’s.

Shor has long encouraged Democrats to do everything in their power to heighten the salience of the party’s most popular economic positions, while reducing the electoral relevance of immigration. This advice is grounded in a concern with the party’s steadily eroding support among non-college-educated white voters, who often lean left on matters of economics but right on those of borders. He often notes that in 2012, when Barack Obama and Mitt Romney framed their race as a referendum on whether the wealthy had “built” all they owned, the Democrat won 60 percent of the “pro–universal health care, anti-amnesty for the undocumented” vote. Four years later, when Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump both centered their messaging on conceptions of American identity — with the former championing multicultural diversity (“stronger together”), and the latter, white ethno-nationalism — the Democratic nominee’s support from pro-socialized medicine, anti-amnesty voters dropped by 19 points. Since Americans of this ideological bent are overrepresented in Rust Belt battlegrounds, that decline was sufficient to cost Clinton the presidency.

This said, it isn’t all that difficult to reconcile Shor’s prescription with Equis’s analysis. It could simultaneously be true that increasing the salience of immigration helps Democrats with conservative Hispanic voters and that doing so would nevertheless be electorally unwise. For one thing, there are a lot more non-college-educated white voters in the United States than there are Hispanic voters of all ideological stripes, and the former also enjoy disproportionate representation in Congress and the Electoral College’s swing states. Further, one interpretation of Equis’s findings is that, at the end of the day, marginal Hispanic voters may be more concerned about their economic security than they are about immigration policy. In the peculiar context of the 2020 election, economic concerns may have pulled these voters right. But if Joe Biden presides over a post-COVID economic boom — as most analysts now expect — then there’s little reason to assume that Democrats won’t boast an advantage with Hispanic voters on bread-and-butter issues in 2024.

Regardless, whatever implications Equis’s findings may have for Democratic strategy, they should make the party a bit less anxious about the 2020 results. A large portion of Trump’s gains seem to have come from ideologically mercurial (and/or nonpartisan) voters who were motivated by cycle-specific factors: God willing, “Do you want the country to be run by a celebrity businessman, or the guy who’s more open to shutting down the economy in order to quell the ongoing mass death event?” will not be a pertinent question in 2024.